The “Queen of Soul,” singer-songwriter Aretha Franklin died today at age 76. Her 1967 recording of the song “Respect” was among the first inductees into the Library’s National Recording Registry when it was established in 2002. This guest post by Cary O’Dell in the Library’s Motion Picture, Broadcast and Recorded Sound division first appeared as an essay in a series on Registry titles, and we present it here in honor of the artist and her work.

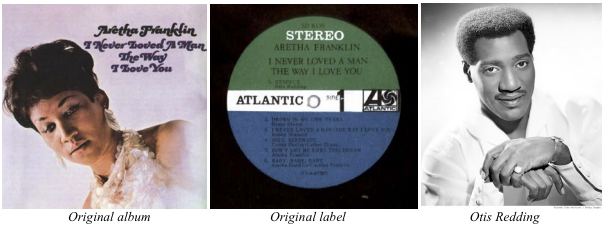

Almost unbelievably, Aretha Franklin was not the first person to record “Respect.” Otis Redding would have those honors when he released his original composition on the Stax label in 1965. And though Redding’s rendition is hard driving and horn heavy, and was a modest hit, it would be Lady Soul’s reinterpretation two years later that would forever lodge in America’s collective memory.

Franklin (1942-2018) had been singing since she was a little girl, growing up in her father’s, the Reverend C.L. Franklin, New Bethel Baptist Church in Detroit. By 1967, Franklin was singing gospel, soul and rock tunes and had already cut numerous sides for the Columbia label. She had even scored a pop hit, a cover of “Rock-a-Bye Your Baby with a Dixie Melody,” in 1961. In 1966, she switched to the Atlantic label; there she would do her most important and prolific work. In 1967 alone she charted with the following singles: “Respect,” “Chain of Fools,” “You Make Me Feel Like a Natural Woman,” “Baby, I Love You,” and “I Ain’t Never Loved a Man (the Way I Love You).”

Lots of landmark music appeared in 1967. Also making the charts during that 12-month period: “Light My Fire” by the Doors, “All You Need is Love” by the Beatles, “Reflections” by the Supremes, “White Rabbit” by Jefferson Airplane and “A Whiter Shade of Pale” by Procal Harum.

Nineteen sixty-seven was not only an important year in music, it was also an important one in American history. It was the year of the race riots in the US; violent, racially-charged outbursts broke out all over the country—in Minneapolis, Detroit, Milwaukee, Washington, D.C., and Buffalo, N.Y. Meanwhile, late in the year, in New York, an anti-Vietnam War protest resulted in more than 200 arrests including activists Dr. Benjamin Spock and Allen Ginsberg. That same year, the National Organization of Women (NOW) published its Bill of Rights which included among its goals the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) and the repeal of all antiabortion laws.

Amidst this turmoil, Franklin’s “Respect,” her proclamation-cum-edict, resonated with a variety of listeners—African-Americans, women, and the youth of America. As Franklin states in her autobiography, “It [reflected] the need of a nation, the need of the average man and woman in the street, the businessman, the mother, the fireman, the teacher—everyone wanted respect. It was also one of the battle cries of the civil rights movement. The song took on monumental significance.”

It was Franklin’s producer Jerry Wexler who first brought “Respect” to the singer’s attention. It was at a recording session in New York City. Franklin was already familiar with Redding’s recording but, sitting at the piano that day with her sister Carolyn in attendance, the two women began to play with the song’s tempo and phrasing. Continuing to work on the song with Wexler, Franklin added a bridge by sampling a bit of Sam and Dave’s “When Something is Wrong with My Baby.” Working with her sister, Franklin added some additional lyrics including the now legendary “Sock it to me, sock it to me!,” later appropriated by the TV program “Laugh-In.” For her version, Franklin retained the song’s signature spelling feature (“R-E-S-P-E-C-T!”) and its reference to “TCB,” an anagram for “Take Care of Business” then popular in the African American community and later adopted and publicized by Elvis Presley.

Aretha Franklin, 1968. Photo by Lee Friedlander. Prints and Photographs Division www.loc.gov/item/2007684747/

Whether it was due to the new arrangement, Franklin’s voice, or the fact that she’s a woman, Franklin’s version seems to have a greater urgency to it than Redding’s did. Franklin brings to the song all her soul and gospel fervor. As music historian Dave Marsh states, “She knows exactly where the song is headed and propels it there with single-minded intensity. There’s not a ‘Hey baby’ or a ‘Mis-tuh!’ that’s accidental. Had Aretha not been trained in the church, she’d never have known what to do here.” And as “Time” magazine noted, “What really accounts for her impact goes beyond technique; it is her fierce, gritty conviction. She flexes her rich, cutting voice like a whip; she lashes her listeners—in her words—‘to the bone, for deepness.’”

For whatever reason, Franklin’s version performed better on the charts than Redding’s did. While Redding’s version went to #35, Aretha’s went all the way to #1. And despite a plethora of other mega-hits by the artist, it was Franklin’s most famous and requested song.

Along with being a staple of Franklin’s catalog, the song also found a home in a million movie soundtracks and on innumerable TV episodes. Other artists have covered it as well, including Ike and Tina Turner, Janis Joplin, Reba McEntire, Kelly Clarkson (and many other “American Idol” alums), Dexy’s Midnight Runners and Justin Bieber.

As much as “Respect” meant to listeners at the time of its initial release, it seems to mean as much to people today. The song has become an anthem for women (an area Franklin would revisit with her 1985 duet with Annie Lennox, “Sisters Are Doin’ It for Themselves”), for blacks, for the bullied, for anyone who has ever felt or feels marginalized.

In recent years, few words have been bandied about more–from the op-ed page to the playground–than the word “respect.” Whether it’s demanding it or decrying it (“disrespect”), whether it shouts from T-shirts or bumper stickers, or emanates from rappers or politicians, it seems everyone is talking about having and showing “respect.” It is both a mandate and a cultural movement, one that comes equipped with its own theme song already attached.