This post draws on an essay about Baldwin’s life and achievements by Alan Gevinson of the Library’s National Audio-Visual Conservation Center.

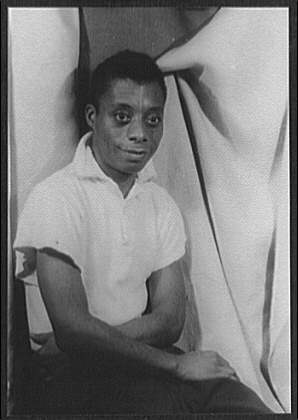

Photograph of James Baldwin from the Carl Van Vechten Collection. LC-USZ62-42481.

James Baldwin was born 93 years ago today, on August 2, 1924, in New York City. His many novels include his first, “Go Tell It on the Mountain” (1953), considered an American classic. He was also a poet and a playwright, but he is most well known and remembered as an essayist and social critic.

The Library of Congress has several notable audio recordings of Baldwin in its collections, including a December 10, 1986, lecture Baldwin gave at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., a year before he died. In it, he reflects on the meaning and impact of race in American life, a subject he investigated from the start of his writing career in the 1940s.

The lecture is one of nearly 2,000 recordings in the series “Food for Thought: Presidents, Prime Ministers and Other National Press Club Luncheon Speakers, 1954–89,” available on the Library’s website. Other speakers include Leonard Bernstein, Fidel Castro, Bob Hope, Nikita Khrushchev, Richard M. Nixon and Jonas Salk. The Library’s recordings of Baldwin, including his National Press Club lecture, are embedded at the end of this post.

Baldwin grew up in Harlem, the eldest of nine children. “I began plotting novels at about the time I learned to read,” Baldwin reminisced in an autobiographical essay that served to introduce his first collection of essays, “Notes of a Native Son” (1955). In grade school, his principal and teachers fostered his interest in reading and writing, urging him to visit the local branch of the New York Public Library.

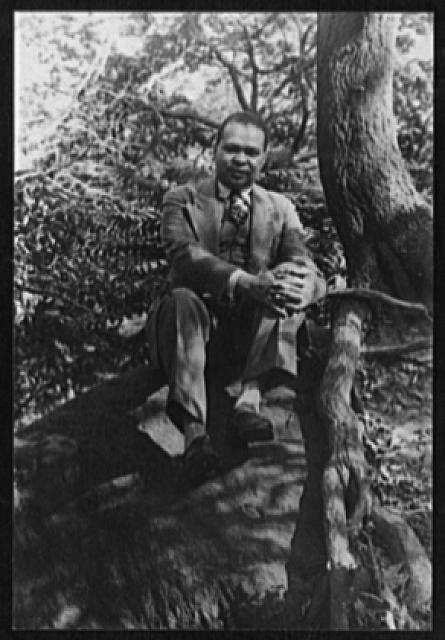

At Frederick Douglass Junior High School in Harlem, Baldwin received encouragement from two African American teachers, acclaimed Harlem Renaissance poet Countee Cullen and Herman W. Porter, a Harvard-educated math teacher, who helped Baldwin run the school magazine.

Photograph of Countee Cullen from the Carl Van Vechten Collection. LC-USZ62-42529

Cullen persuaded Baldwin to attend his own alma mater, DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, considered one of the top public schools in the city. Interested mainly in English and history, Baldwin became an editor of the school’s literary magazine, The Magpie, to which he contributed stories, plays and poems. During high school, Baldwin also preached at a Pentecostal storefront church in Harlem, where his stepfather was a preacher. His novel “Go Tell It on the Mountain” draws on his experiences there.

Baldwin was inspired in the 1940s by American modernist painter Beauford Delaney, whom he viewed as “living proof . . . that a black man could be an artist.” Baldwin spent time listening to jazz and blues recordings in Delaney’s Greenwich Village studio, an experience Baldwin described as spiritually meaningful. He later credited Delaney with teaching him to observe reality closely and to honestly confront disturbing phenomena.

Baldwin moved to Greenwich Village himself after a dispiriting year as a laborer at a defense-related construction site in New Jersey, where he endured racial prejudice. In Greenwich Village, he began to explore his sexual identity and commenced his professional career as a writer. He initiated a meeting in 1944 with Richard Wright, author of the acclaimed 1940 novel “Native Son.” After reading Baldwin’s work, Wright recommended him to his editors at Harper and Brothers publishers.

Beginning in 1947, Baldwin published essays and book reviews in The Nation, The New Leader, Commentary and Partisan Review. His first short story to appear in a major publication, “Previous Condition,” was published in Commentary in October 1948.

The next month, Baldwin moved to Paris, feeling that he had reached the limit of his tolerance for racial prejudice and eager to develop his literary career in a broader context. In the years following, he produced some of his most famous work, including “Go Tell It on a Mountain” and “Notes of a Native Son.” His work addressed complex pressures arising from integration not only of African Americans, but also of gays and bisexual men. Other titles include the novel “Giovanni’s Room” (1956), in which he explores the issues of race, sexuality and identity; the bestseller “Nobody Knows My Name: More Notes of a Native Son” (1961); the novel ”Another Country” (1962); and “The Fire Next Time” (1963), a book of two essays.

Although he lived outside the U.S. for much of his life, Baldwin’s writing remained focused intently on the American experience. He became a leader of the U.S. civil rights movement and on May 17, 1963, Time magazine featured Baldwin on its cover, stating, “There is not another writer who expresses with such poignancy and abrasiveness the dark realities of the racial ferment in North and South.”

In a December 1986 interview, shortly before he appeared at the National Press Club, Baldwin described writing as an act of faith. “The time of any artist—the time of any person—is brief. But that does not mean that he or she doesn’t have an inheritance which one way or another he is compelled to pass down the line. So you work in the dark; you work in your time. The only real sin is despair . . . and you try to tell the truth.”

James Baldwin died on December 1, 1987, at his home in France.

Scroll down for recordings of Baldwin: an April 1986 reading by Baldwin at the Library of Congress, introduced by poet Gwendolyn Brooks; the December 1986 National Press Club recording cited in this post; and an audiovisual interview Baldwin conducted in San Francisco in 1963 for a television documentary on the racial situation in the U.S.

{mediaObjectId:'2E46DF99C58F017CE0538C93F116017C',playerSize:'mediumStandard'} {mediaObjectId:'3BEEDEC7854F005CE0538C93F116005C',playerSize:'mediumStandard'} {mediaObjectId:'2C86B06B441100EEE0538C93F11600EE',playerSize:'mediumStandard'}Click Here to Read More