This is a guest post by American Folklife Center archivist Kelly Revak. An expanded version appeared in “Folklife Today,” the center’s blog.

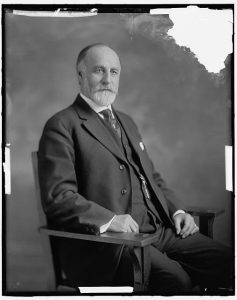

Anthropologist Jesse Walter Fewkes, 1905. Photograph by Harris and Ewing.

Did you know that today is National Tell-a-Joke-Day? Neither did I, until one of my colleagues informed me. But it is timely, because I believe I have found the earliest audio recording of a joke being told. Read on for the full story and listen to the recording. But be forewarned: it’s a political joke!

When I joined the Library’s American Folklife Center as an archivist, one of my first tasks was to catalog ethnographic recordings of Passamaquoddy Indian tradition bearers made in 1890 by Harvard anthropologist Jesse Walter Fewkes (1850–1930). He was the first to use a wax cylinder recording machine, or phonograph, for ethnographic research. He brought one of the machines, invented by Thomas Edison, to Calais, Maine, in March of that year to record songs and stories of two Passamaquoddy tradition bearers. These recordings, as well as Fewkes’s Hopi and Zuni recordings, are fairly well known and were preserved as a part of the Federal Cylinder Project in the 1970s.

Less well known are several other recordings Fewkes made in his earliest days with the phonograph. While cataloging the Passamaquoddy recordings, I came across a group of cylinders noted to hold unidentified ethnographic recordings as well as several experimental recordings by Fewkes. I listened to recently digitized files of the cylinders and found some things relevant to the Passamaquoddy Collection. But I also found myself delighted by Fewkes’s personal and experimental recordings and discovered several items of interest, including folk songs, whistles, narratives, recitations—and outright clowning around. Because most of these have never been cataloged, they represent a largely untapped body of data.

One cylinder in particular was clearly shaved and rerecorded a number of times, showing the remnants of several recording sessions on it. The remaining audio is informal, without introduction, and is a fascinating example of American humor at the end of the 19th century. As far as I’ve been able to determine, it may be the earliest surviving audio recording of a joke.

Earlier humorous recordings exist, but I have found nothing you could clearly classify as a traditional joke. What exists is more along the lines of humorous spoken monologues. For example, a funny 1888 recording titled “Phonograph Talks with Mr. Edison” features recording pioneer George Gouraud pretending to be a little person hiding inside the phonograph machine making the sounds you hear.

Fewkes’s joke, which seems to have been recorded casually, is likely from 1890 or 1891.

Listen here:

{mediaObjectId:'53AD3FE4339E00C2E0538C93F11600C2',playerSize:'mediumStandard'}

An Englishman and an American were once discussing the McKinley Bill, and the Englishman said, ‘If you do pass that bill, we shall have to come over to your country and give you a thrashing!’ And the American said, “What, AGAIN?!”

If you are like me, and not deeply steeped in economic policy debates of the late 1800s, then this joke might not be immediately funny.

The late 1800s saw a fierce and protracted debate over tariff law that has never really been totally resolved. Republican protectionists favored heavy tariffs on imported goods to protect newly forming domestic industries, while Democrats were pushing to remove trade restrictions altogether. Drawing on heightened Anglophobia of the time, protectionists made anti-British themes a central part of their campaign. In 1890, Republican Rep. William McKinley of Ohio sponsored a tariff bill, dubbed the “McKinley Bill,” which explains the reference in the joke. It passed in October of that year, raising the average duty on imports to almost 50 percent.

Contemporaneous versions of this joke can be found in print. All use it as part of a larger narrative to advocate protectionist viewpoints, make light of British bluster or note American wit. The joke mocks any potential retaliation by the English, implying that England would try, and fail, to reclaim its recalcitrant territory, as it had in multiple preceding conflicts.

Without knowing how Fewkes might have used the joke, it is difficult to tell what his aims were in telling it. But it certainly says much about his politics, and actually hearing him tell it gives a sense of his personality and humor. In the case of this particular joke, listening to the audio is also extremely helpful, because the humor relies so significantly on intonation. It is the exaggerated incredulity in Fewkes’s voice that makes the sarcasm clear.

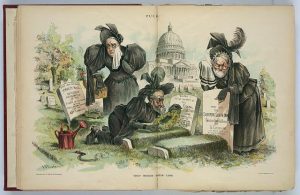

A cartoon from Puck magazine depicts a headstone (far left) mourning the demise of the McKinley Bill. It reads, “Here lies our dear McKinley Bill. Ruthlessly assassinated in the flower of its youth by the tariff reform bandits of the 53rd Congress.”

So is it the earliest joke? The cylinder has no definite date; however, several contextual elements allow a reasonable placement:

- The cylinder came from the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology Miscellaneous Cylinder Recordings Collection. Fewkes worked for the Peabody Museum only from 1889 to 1894. (The American Folklife Center received over 250 cylinders from the Peabody Museum in 1970.)

- The “McKinley Bill,” officially the “Tariff Act of 1890,” was introduced and passed that year. When Democrats won control of the presidency, Senate, and House after the 1892 election, they immediately started drafting new tariff legislation. Because of the specific reference to the “McKinley Bill,” it is probable that the joke was told between 1890 and 1892.

- All other cylinders in the same record group that include dates are from 1890 and 1891.

The next earliest known recording that includes jokes was made in late 1892.

For a long time, informal recordings have been given short shrift in catalogs and have been largely overlooked for research. Yet they are interesting precisely because they are less rehearsed and self-conscious than much of the commercially produced sound that would soon follow. They are ethnographic recordings of the collectors themselves—they turn the lens on the ethnographer as informant.

So whether or not the Fewkes cylinder does in fact contain the earliest sound recording of a joke—and I invite anyone to prove me wrong!—it demonstrates the value of informal recordings as rich bodies of data for late 19th-century culture, as well as interesting markers in the history of recorded sound.