“Game of Thrones” is back for its final season, and the fate of Westeros may well depend on how the ice dragon (Viserion), now the winged weapon of the White Walkers, fares against his still-living counterparts.

If you’re still reading, you know that the HBO series is based on George R.R. Martin’s books, which are, in turn, loosely based on England’s Wars of the Roses, the dynastics battles that raged between 1455-1485. No doubt you are aware that medieval battle was not for the faint of heart. But Martin’s use of dragons in his “A Song of Ice and Fire” epic is not as fanciful as one might think. One of the medieval era’s most influential military war manuals really did sketch out the idea of using a dragon on the battlefield.

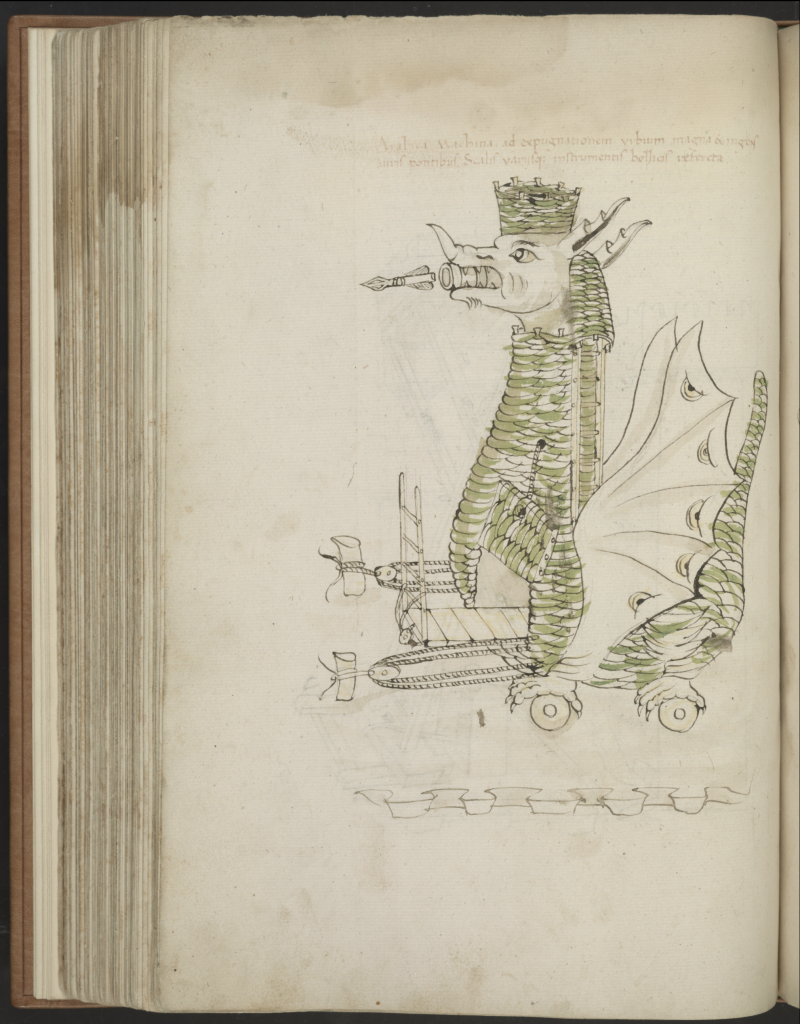

Behold, knaves, we give you the dragon war machine of yore:

Illustration from manuscript of “De re militari,” Roberto Valturio, ca. 1460. The Lessing J. Rosenwald Collection, Library of Congress.

Try not to tremble from its awesomeness.

This is from “De re miltari” (“On military matters”) an illustrated folio written by Roberto Valturio, an Italian engineer and technical adviser to Sigismondo Malatesta, the Renaissance Lord of Rimini, who commissioned it. The volume no doubt drew upon a famous Roman manuscript of the same name, but the woodcut illustrations, attributed to Matteo de’ Pasti, are truly original. The nearly 400-page volume, written between 1446 and 1456 in manuscript form (of which the Library has two copies in the Lessing J. Rosenwald Collection), gained wide popularity across Europe. Malatesta — a powerful prince, patron of the arts and military ruler — distributed these to royal houses, such as those of Louis XI. This was not hubris. His family was so famous than a wife-killing ancestor was included in Dante’s “Inferno.”

“The intention was to send it out to kings and important statesmen throughout Europe,” says Stephanie Stillo, a curator in the Library’s Rare Book and Special Collections Division. “It’s interesting to think why Malatesta would do it. There are no military secrets. It’s all pretty well-known. But it’s sort of a power play, this commander sending out definitive military manuscripts that are extraordinarily illlustrated.”

When it was printed in Verona in 1472 (after Malatesta’s death), it became the first book printed with technical or scientific illustrations, and was the second book printed in all of Italy. So profound was its impact, so ubiquitous were its standards, that Leonardo da Vinci used it as a reference volume.

For the military man, the volume drew on well-established principles of siege warfare. There are a few technical drawings of cannons (the newest thing at the time), but most are of battering rams, catapults and ladders for scaling castle walls. Some of these are beautifully rendered, with decorative heads of rams or wolves. On the “these projects are in research and development” front, there are sketches of rudimentary flotation devices, one apparently made from pig skin — with the pig’s head still attached. There’s even what could be called an early cherry-picker, in which soldiers could be hoisted above castle walls, so that they could fire down on the enemy. Over time, the book became ingrained in medieval history. It is well known to scholars today.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if the people working on ‘Game of Thrones’ consulted this,” Stillo says.

Illustration from manuscript of “De re militari,” Roberto Valturio, ca. 1460. The Lessing J. Rosenwald Collection, Library of Congress.

But in the book, in the midst of so much 15th Century practicality, of such utilitarian means of warfare, there is, at the flip of the page…well, a dragon. In the manuscript copies that are hand-colored, it is of a modest green, with sharp eyes, large wings and three horns. The military idea seems to be a medieval update on the Trojan Horse — a mysterious device that could be rolled up to castle walls. Note the claw-covered wheels and the stomach flap that opens out and up, so concealed troops could leap into battle. In some editions, there are openings for cannons from its haunches. In all of them, though, the dragon is wearing a stately hat and shooting gargantuan arrows from its mouth.

Detail from “De re militari, “Roberto Valturio, 1472 printed edition. The Lessing J. Rosenwald Collection, Library of Congress.

“Nobody knows quite what to call it,” Stillo says. “It’s just a floating, rolling…dragon war machine.”

We regret to report that there are no surviving battle reports of this device actually in use, and we are pretty sure people would have remembered if it had. Still, in that era of grim military tactics and brutality, it is hard to blame Valturio or Malatesta for this flight of fancy. The good tactician seeks advantage in surprise, and nothing would have been more surprising in the midst of medieval battle than to see this monstrosity looming in the mist.