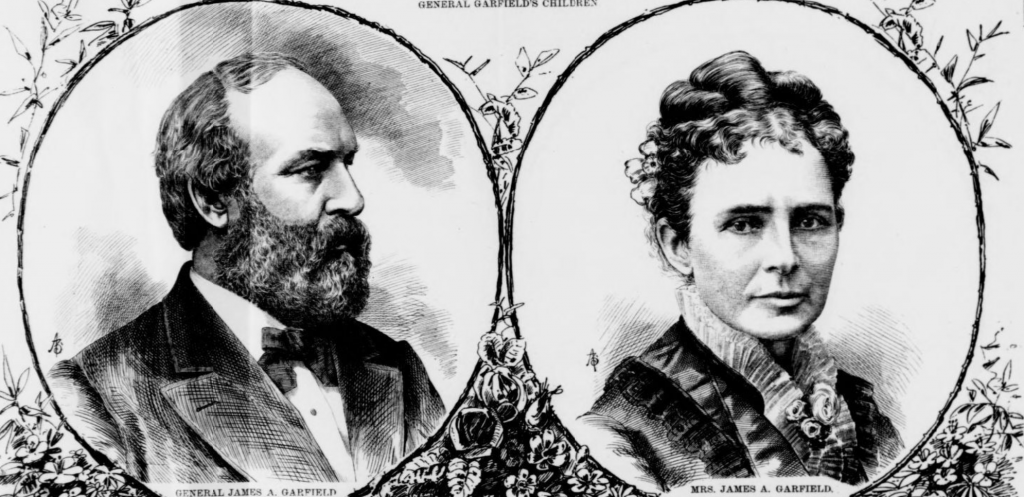

James and Lucretia Garfield, depicted in unnamed publication, ca. 1880

This is a guest post by Michelle Krowl, a historian in the Manuscript Division. It’s a lovely piece about how the slow-burning passion of the couple developed over years of time. “It is nearly ten o’clock Sunday night and I will not lie down to sleep till I have told you again that I love you,” he wrote to her on Nov. 24, 1867. It’s okay to swoon.

“I have for a series of years been accquainted [sic] with Miss Lucretia Rudolph and have been, for several months studying her nature & mind,” wrote future President James A. Garfield in his diary on December 31, 1853. While he respected her intelligence and her character, one question troubled him as to their romantic prospects: “whether she has that warmth of feeling– that loving nature which I need to make me happy.” The couple’s struggle to answer that question is amply documented in the hundreds of letters they exchanged on the course of true love. Those letters — as well as the former president’s diaries, professional and family correspondence, scrapbooks, speeches, and other materials relating primarily to his career and death — are now available online from the Library.

James A. Garfield’s Greek class, Western Reserve Eclectic Institute, Hiram, Ohio, 1853. Garfield (far right, front row) is next to his future wife, Lucretia Rudolph.

The pair met at school in Ohio in the 1850s. She was nicknamed “Crete,” short for Lucretia. (I’ll refer to them by their first names for this rest of this post, to avoid confusion as to which “Garfield” I might be referring.) James’s passionate nature demanded that he “know & be known,” and he remained skeptical that the emotionally reserved Crete could give him the affection he craved. For her part, Crete vowed to “never give my hand to one who has not my heart.” Their romance blossomed, however, and they were engaged when James left Ohio in 1854 to attend Williams College in Massachusetts. They sustained their relationship through letters, but the physical distance tested James’s resolve after he became enamored with Rebecca Selleck of New York. James assured Crete that his love for her was “not a wild delirious passion, a momentary effervescence of feeling, but a calm strong deep and resistless current that bears my whole being on toward its object.” Yet a painfully awkward meeting of James, Crete and Rebecca at James’s graduation in 1856 exposed intense feelings and strained James and Crete’s relationship. When James dithered in making a decision, Crete took matters in hand, absolving James of blame for the “generous and gushing affection of your warm impulsive nature” and giving him permission to marry Rebecca if “you love her better, if she can satisfy the wants of your nature better.” Better to release him, Crete explained, than “to be an unloved wife, O Heavens, I could not endure it.”

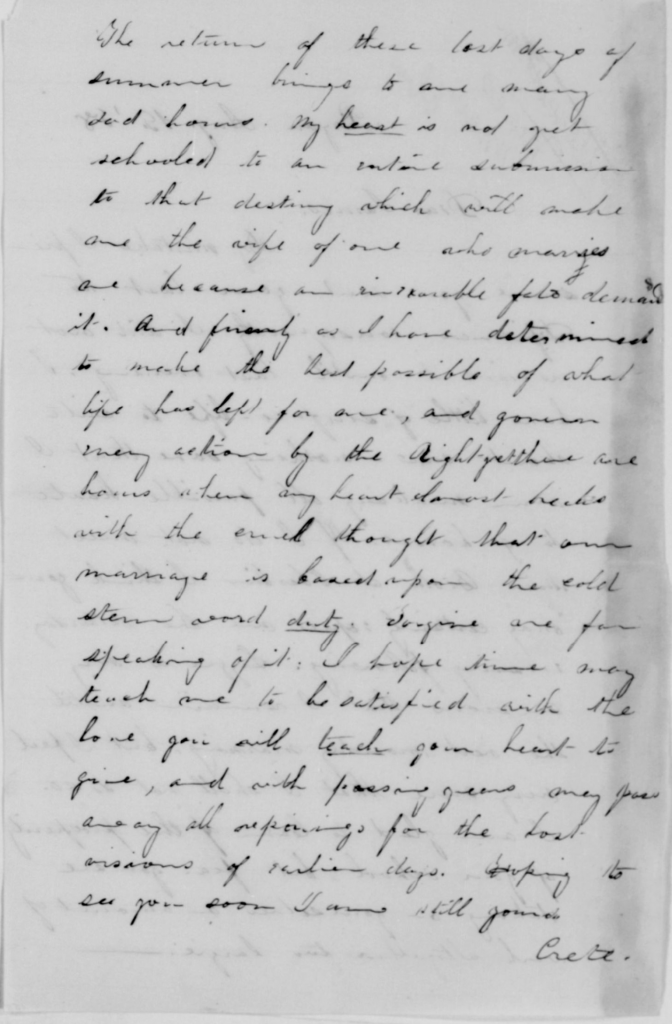

Lucretia Rudolph to fiancé James A. Garfield, August 19, 1858, expressing her fears that their marriage will be based on “duty.”

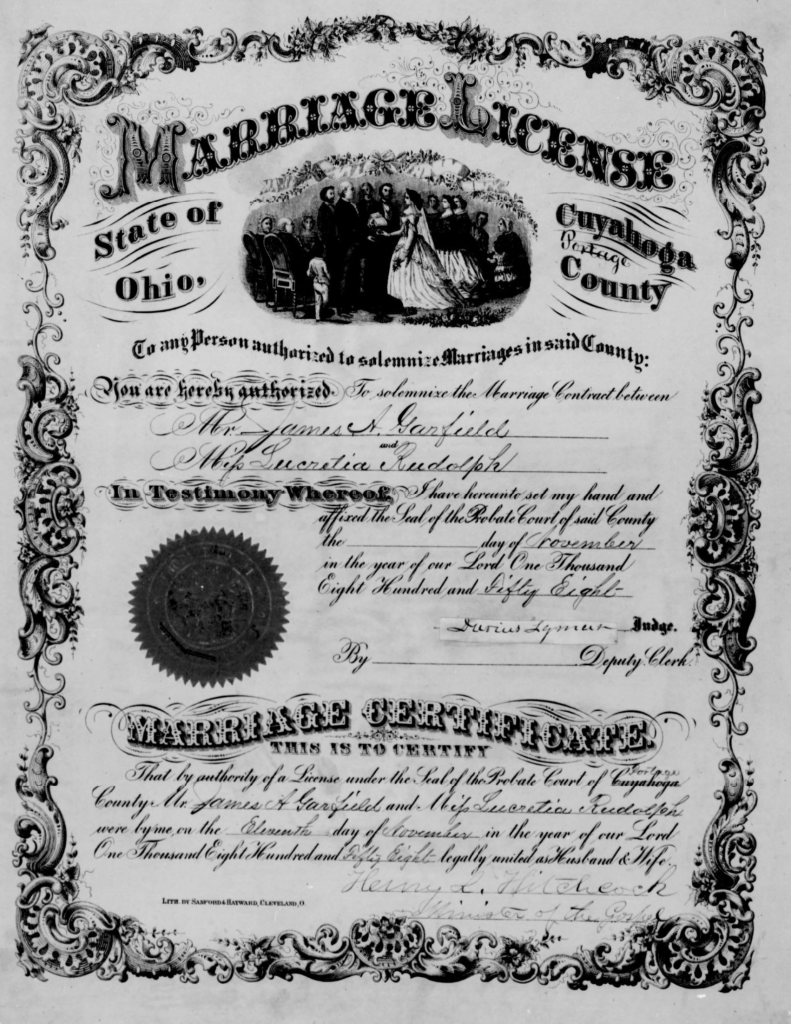

In April 1858, James and Crete resolved to “try life in union.” But James felt “restless & unsatisfied” with his life, and Crete worried that he would marry her “because an inexorable fate demands it.” While she vowed to make the best of their life together, “there are hours when my heart almost breaks with the cruel thought that our marriage is based upon the cold stern word duty.” James wed Lucretia on November 11, 1858, hopefully with more enthusiasm than his stark diary entry suggests: “Was married to Lucretia Rudolph….”

Marriage license of James A. Garfield and Lucretia Rudolph.

Separation, both emotional and physical, characterized the marriage for several years. James stayed busy with a burgeoning political and legal career before going off to war in August 1861. As James’ star rose in the military and after his election to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1863, he and Crete struggled to sustain their frayed relationship. James held out hope on their fourth anniversary that “patient waiting and mutual forbearance has at last begun to bear the fruits of peace and love” after they had “groped about in the darkness and grief trying to find the path of duty and peace, and being so often pierced with thorns.” Crete blamed “the mask my own heart had worn” for their sorrows.

After the death of their daughter “Trot” in December 1863, their severest trial came in 1864 when rumors of an extramarital affair threatened James’ political career and his marriage. James confessed his transgression to Crete, hoping for her guidance and some measure of “respect and affection.” Crete offered sage advice, and forgiveness.

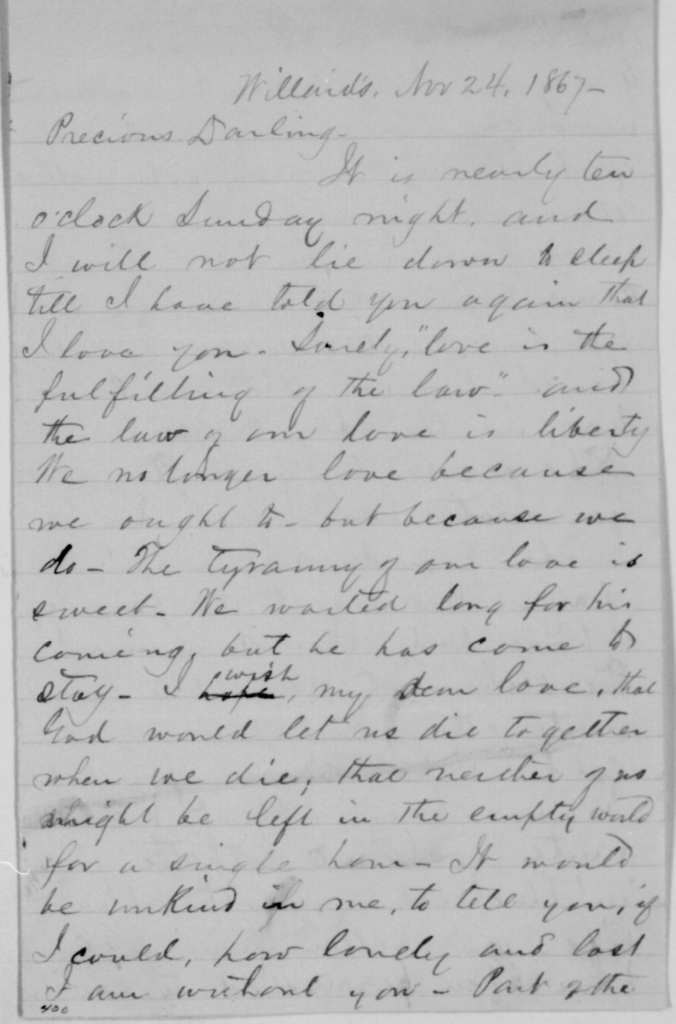

While painful for both, the episode seemed to awaken in James and Crete a genuine intimacy previously missing in their marriage. Their subsequent letters reflected a deep longing for and commitment to one another. “We no longer love because we ought to, but because we do,” James explained, and promised that “were I now alone, and with an unwedded hand and heart, but knowing your nature as I now know it, I would woo only you, and use all the powers of honor and effort to win you and make you mine.” To his “Precious Darling” he expressed the wish “that God would let us die together when we die; that neither of us might be left in the empty world for a single hour.”

James A. Garfield to his wife Lucretia, November 24, 1867: “We no longer love because we ought to, but because we do.”

Alas, an assassin’s bullet thwarted James’s wish in 1881, leaving Crete a devoted widow until her death in 1918. But their letters are eternal, and through them we can share in the extraordinary love story of James and Lucretia Garfield.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.