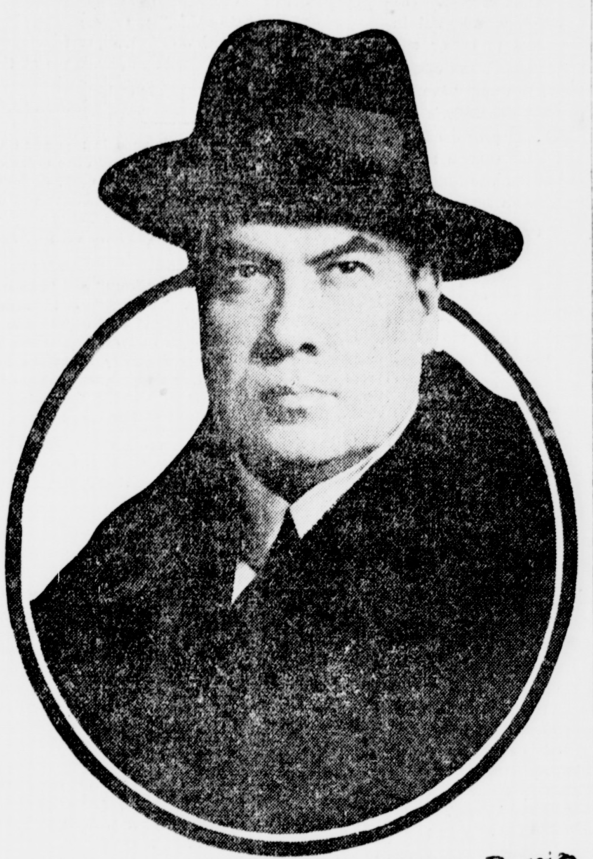

Ruben Dario, as pictured in a New York Tribune story on Feb. 8, 1915.

This is a guest post by María Peña, a public relations strategist in the Library’s Office of Communications.

Nicaraguan poet Rubén Darío has been dead for over a century, but on the cobblestoned streets of his hometown, renamed Ciudad Darío in his honor, and throughout Spain and Latin America, his poetry and prose continue to inspire generations of writers.

His given name was Félix Rubén García Sarmiento, but he was known to all as Rubén Darío. During his career, spanning the late 19th and early 2oth centuries, he became one of Latin America’s greatest poets, eventually known as the father of modernism.

He died 105 years ago this Saturday at age 49, from complications to alcoholism. But his work has proven timeless, as his name is today emblazoned everywhere in the Spanish-speaking world — metro stations, street signs, statues, schools, parks and squares. The National Library of Nicaragua is named for him. The Library of Congress holds more than 500 volumes by or about Darío, including the 1905 edition of his masterpiece, “Cantos de vida y esperanza” (“Songs of Life and Hope.”)

I recently interviewed Nicaraguan writer Sergio Ramírez about Darío’s life and legacy. In 2016, Ramírez published “A la mesa con Rubén Darío,” a book about the poet’s little-known life as a foodie.

The interview, originally in Spanish, has been edited and condensed for clarity.

How relevant is Rubén Darío’s body of work today?

Sergio Ramírez. Photo: Margarita Montealegre.

Rubén Darío´s poetry is undoubtedly relevant in the Spanish language. As (Argentine writer) Jorge Luis Borges once said, “Everything changed with Darío.”

Borges called him the “liberator of language” because he transformed it. Modernism as such did not remain a mere pyrotechnic game with the novelties it brought.

Darío led a current that revolutionized language and breathed life into it. His legacy lives on not only in the poets that came after – like (Nobel Prize laureate) Juan Ramón Jiménez, who was his disciple — but also in others he influenced, like César Vallejo and Pablo Neruda.

He was called “the Prince of Castilian letters” and he continues to be read. “Cantos de vida y esperanza” is considered his masterpiece because it reflects his full maturity as a poet.

He was a prodigy. He learned to read when he was three and published his first poems as a teenager.

He had a gifted memory from a very young age. He was only 17 when he traveled to Chile but already he had a vast cultural knowledge.

In his autobiography, Darío fondly remembers the house he grew up in in León with his aunt and uncle, surrounded by books like Cervantes´ “Don Quixote,” and how he´d climb up the branches of a jícaro tree to read undisturbed.

When Darío moved to Managua to work at the first national library, he´d spend hours reading the Spanish classics. And that was very significant, in a country so rural and poor, so small and underpopulated, so ravaged by years of civil wars and pandemics.

How did that experience inform his work and his world view?

There are two things worth noting here: Like a sponge, he absorbed everything from his readings, the landscapes, his understanding of people, the very essence of Nicaraguan identity. There´s a beautiful poem he wrote about Nicaragua bearing fruits “from a small womb,” so he was aware of living in a small, poor country.

The other big influence is his messy family life, because his parents had an unhappy marriage and his mom ultimately went to live with her lover in Honduras. This really affected him, and I believe it greatly shaped his later addiction to alcohol.

Yet he was very eclectic: a poet, journalist and a diplomat.

Well, those were facets borne out of necessity, because a poet couldn´t survive on his craft alone. Journalism was his main source of income and he was truly an innovative journalist.

Darío was part of a crop of poets — Amado Nervo, Manuel Gutiérrez Nájera and Julio Herrera y Reissig among them – who were also great journalists and chroniclers of their time. He made good money working for La Nación (Argentina), because he couldn´t rely only on publishing his poetry books.

I don´t think he had great diplomatic qualities, even though he went on to have several diplomatic postings.

Was poetry a refuge for Darío?

Darío had problems with alcoholism, but he was a very disciplined writer. If he didn´t file stories he wouldn´t get paid to support his family. And he continued writing poetry.

Darío was an essential poet; he couldn´t have been anything else in life. His poems show a deep understanding of classical Greek, Latin and Spanish culture. Salvadoran writer Arturo Ambrogi once visited him in his Paris studio and found his table full of dictionaries and reference books on Greek mythology and other topics. He approached his work with diligence.

The world knows Darío as this gifted modernist writer, but you wrote about him being a “foodie” before the term existed.

He loved fine dining, but he wasn´t dining at fancy restaurants every night, drinking champagne or eating quail or pheasant. Food was something Darío was interested in as a core cultural topic and wrote about French and Spanish cuisines. He also loved Nicaraguan dishes, and he taught Francisca Sánchez (his Spanish mistress) how to prepare them.

In an era of tweets, emojis and short attention spans, how do you entice young people to read Darío and other great poets?

Some would argue social media is an enemy of culture, but I think it’s a powerful tool for teaching profound subjects. Look at how this pandemic has moved learning online. Social networks have created opportunities to democratize culture and mass communication.

I´m not concerned about the silly things people share, because there´s lots of learning that can happen, too. I believe Nicaragua has the most poets per kilometer squared. People enjoy writing and publishing poetry not because they want to be recognized as great poets, but more for spiritual relief.

What is the best way to remember Darío and honor his legacy?

I believe the best way to do so is by reading his works and teaching them. There´s Darío and his musical poems, and Darío the storyteller in verses like “Margarita está linda la mar,” but there´s also his existential poetry.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.