Tulsa’s Greenwood District after the massacre. Photo: American Red Cross. Prints and Photographs Division.

This is a guest post by Wanda Whitney, Head of History & Genealogy, Researcher and Reference Services.

This week marks the 100th anniversary of the Tulsa Race Massacre, in which a mob of whites invaded and burned to ashes the thriving African American district of Greenwood, also known as Black Wall Street.

It was, then and now, among the bloodiest outbreaks of racist violence in U.S. history. The official tally of the dead has varied from 36 to nearly 300. White fatalities are documented at 13. Some 35 square blocks of Black-owned homes, businesses, and churches were torched; thousands of Black Tulsans were left homeless – and yet no local, state or federal agency ever pursued prosecutions. The event was so quickly dismissed by local officials that today, a century later, several local organizations are still investigating reports of mass graves.

I became interested in what happened in Tulsa when I watched the 2019 HBO series, “Watchmen,” which opens with a depiction of the massacre. I had heard about the Greenwood massacre before but didn’t know much about its history. Then late last year, a patron contacted our Ask a Librarian service with a question about racial massacres. That spurred me to investigate the Library’s collections to see what I could find out about the Tulsa massacre and similar events that occurred in the United States in the post-World War I era.

The Researcher and Reference Services Division put together a guide to conducting your own research. But first, let’s establish some context and basic facts, as the massacre occurred against the broader canvas of post-World War I racial unrest that bubbled up across the nation.

In 1919, Black soldiers, returning from the battlefields of Europe, expected that their sacrifices and service to the nation would be recognized by whites, that Jim Crow segregation and state-sponsored racism would be eased. That was not so. By and large, white society sought to enforce the segregated status quo that had existed before the war. A series of racist attacks and deadly fights ensued. It was so bloody that it became known as the “Red Summer.” You can research this era in our research guide, Racial Massacres and the Red Summer of 1919.

In Tulsa, two years later, the situation was much the same on the morning of May 30, Memorial Day, when Dick Rowland, who worked as a shoe shiner, got on an elevator in the Drexel Building in downtown Tulsa. The elevator operator was a white teenager, Sarah Page.

It has never been clear what transpired, but Page said Rowland “attempted to assault” her. Police arrested Rowland the next day, as the Tulsa Tribune ran a short story with the headline: “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in an Elevator.”

By early evening, an angry group of several hundred white Tulsans assembled outside the county courthouse where Rowland was being held. Some were intent on lynching him and tried to break in. Groups of black men, from 25 to 75 strong, many of them veterans carrying their service revolvers, came to help defend Rowland, but were ordered to leave by police.

Then, around 10 p.m., shots were fired in the crowd. Chaos and mass violence broke out, spreading far from the courthouse. The Black groups were quickly outnumbered and outgunned, in part because local officials provided weapons to white men whom they “deputized.” Black residents retreated into their Greenwood neighborhood, but it was no protection. Thousands of white people rushed into the neighborhood at dawn the next morning, looting, burning and killing. Mount Zion Baptist Church billowed smoke and flames. The Dreamland Theater was destroyed. The neighborhood was reduced to rubble.

It was over by noon.

Black citizens being held at the local fairgrounds. Photo: American Red Cross. Prints and Photographs Division.

Thousands of the Black survivors were forced into the city’s fairgrounds, released in the coming days only if a white person vouched for them.

Despite this shocking violence, no city, state, or federal criminal prosecution was ever mounted. The narrative was minimized or scarcely mentioned in public discourse and history books for nearly 50 years. As a commission appointed by the Oklahoma legislature reported nearly eight decades later: “There had been a pattern of deliberate distortion of facts regarding the riot and even the destruction of vital documents and a subsequent coverup.”

This was a sobering record to confront. I suspected that finding information about the Tulsa massacre might not be an easy task. While there were differing newspaper reports and oral histories published at the time of the event, there still remained a dearth of official primary sources or official records to bear witness to what happened. And although we now refer to the event as a “racial massacre,” it was called a “race riot” for many years.

The Library has already begun retitling this event as a “massacre” in our catalog descriptions. Please note, however, that we do not change descriptions of any events in our collection items themselves, such as newspaper accounts or other records contemporaneous with the massacre.

So, to begin your research in our collections, use the keywords, “Tulsa race riot” in the search field on our homepage. For photos, you can filter your initial results to the Photos, Prints, Drawings category. Most of the images come from the NAACP records or the American National Red Cross photograph collection.

You can get a block-by-block look at Tulsa and the Greenwood district in that era with our Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps of the city in 1915.

The Greenwood Business District was bordered by Archer Street at bottom, Detroit Avenue at left and railroad tracks at right. Greenwood Avenue is in the middle of the map, going north to south. Almost all of this area was burned. Sanborn Fire Insurance Map. Geography and Maps Division.

Various newspapers, both local and national, reported the event. You can search our Chronicling America collection for articles about the massacre. For helpful search tips, check out our research guide, Tulsa Race Massacre: Topics in Chronicling America.

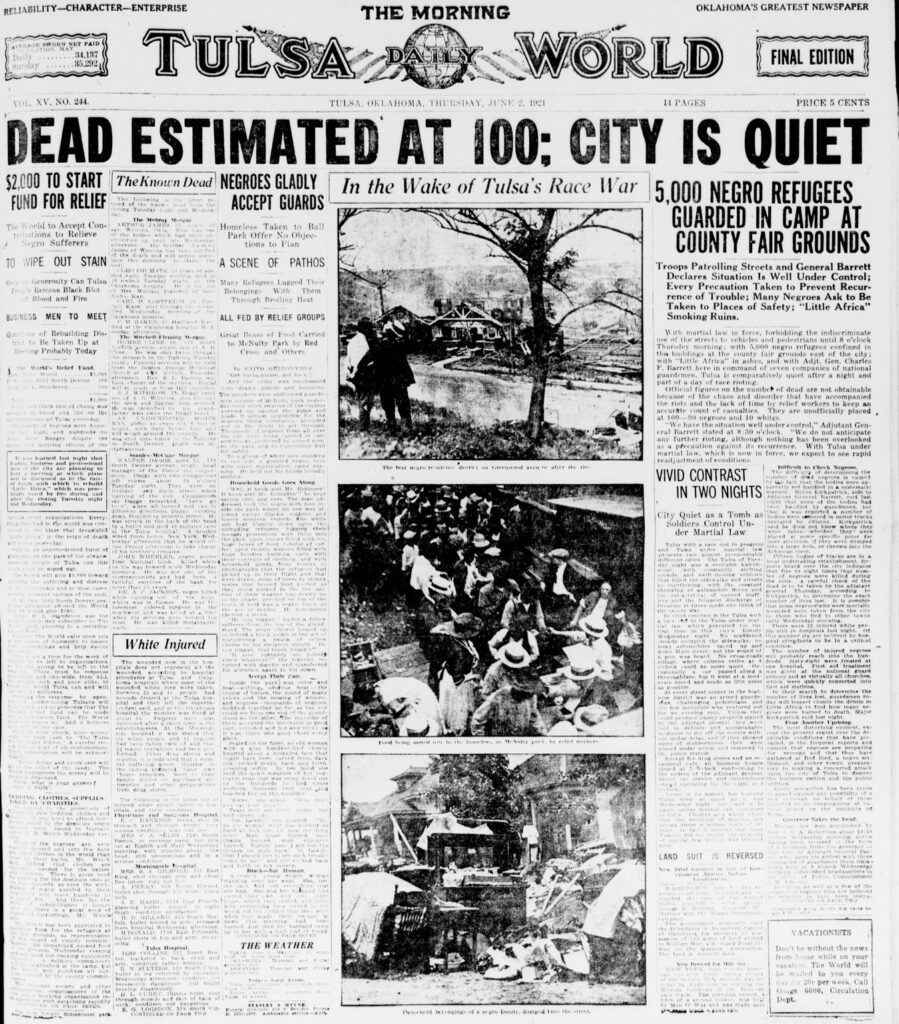

The Tulsa World, Thursday, June 2, 1921. Chronicling America.

The public’s renewed interest in the massacre began with publications about it in the 1970s and 1980s and culminated in the 1997 establishment of The Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921, mentioned above. This legislative Commission put out a national call for survivors who could give interviews for oral histories. It also worked with historians who gathered information about what happened. Their report, published in 2001, became part of the official history. The Library has a print copy of the report. For additional books in our collection, take a look at the print bibliography in the Racial Massacres research guide. There are many books devoted to the massacre, including “Tulsa 1921,” “The Burning,” and “Death in a Promised Land.”

For eyewitness accounts, the Library has oral histories of 3 survivors of the massacre interviewed by Camille O. Cosby for the National Visionary Leadership Project. Other accounts appear in the HistoryMakers database, a subscription database available onsite at the Library. They are fascinating to watch. If you can’t come to the Library, see what your local public library may have on the Tulsa massacre. Other sources of oral interviews, documents, and photos include the Oklahoma Historical Society, Tulsa Historical Society & Museum, and the electronic library, Oklahoma Digital Prairie, among others.

The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission, created in 2015, continues the work of the Oklahoma Commission to tell the history of Greenwood. Look for events in May and June that coincide with the 100th anniversary of the event.

Finally, one note of irony. Rowland, the original target of the violence, was neither harmed nor charged with any wrongdoing. He left town and the rest of his life could not be traced, the Tulsa World reported last year. “Dick Rowland,” the name he gave to police, may not have even been his real one, the newspaper reported. Page, the teenaged elevator operator, had only recently arrived in the city and left soon thereafter, the paper said, and could not be tracked down, either.

I wish you success with your research into this troubling episode in our history. If you have a more specific research request, or need assistance searching for resources, please use our Ask a Librarian service.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.