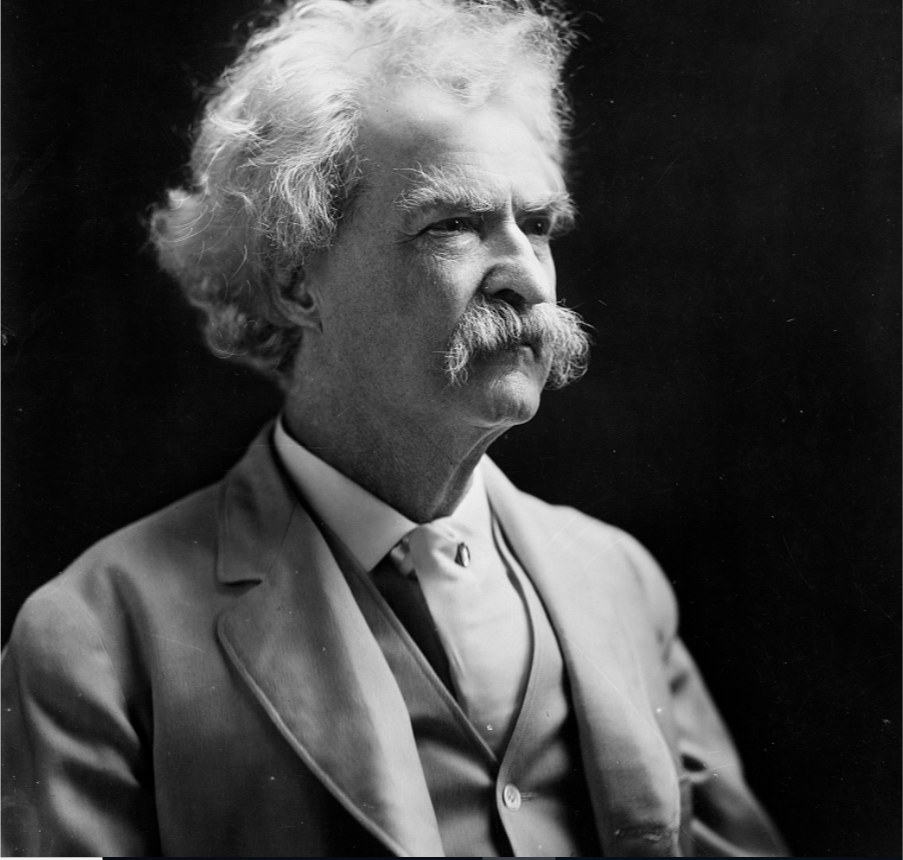

Mark Twain, 1907. Prints and Photographs Division.

Mark Dimunation, chief of the Rare Book and Special Collections Division, wrote this piece on how the young Samuel Clemens perfected his wildly popular speaking tours.

A fledgling reporter in 1866, Mark Twain traveled to Hawaii, then called the Sandwich Islands, as a correspondent for the Sacramento Union. Over the five-month tour, he filed 25 vivid reports of his travels to various California newspapers and the stories captured an audience. Upon his return, he launched a speaking tour throughout California.

Initially, Twain was a hesitant and somewhat awkward presenter. His early take on the subject established his comical recounting of the values and the vices of the islanders. He closed his early programs with an apology for subjecting the audience to his talk, explaining that he needed the money. One early critic noted that his “method as a lecturer was distinctly unique and novel. His slow, deliberate drawl, the anxious and perturbed expression of his visage, the apparently painful effort with which he framed his sentences … All this was original, it was Mark Twain.”

That initial tour was so extraordinarily profitable that it established a new career for him.

Twain repackaged the lecture three years later for a tour of the Northeast. The talk was called, “Our Fellow Savages of the Sandwich Islands.” (As one would imagine, this is a talk infused with Twain’s comic sensibility as well as a decidedly 19th-century notion of social/political correctness. His comic lines are the ones that endure.)

He would eventually give this talk in various locales more than 100 times. “I shall tell the truth as nearly as I can,” he always liked to say, “and quite as nearly as any newspaperman can.”

A flyer advertising Twain’s speaking tour. He made up the insulting reviews, including the cannibalistic review from the Sandwich Islands. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

His cultural observations ranged from fairly serious tales of the islands’ volcanoes to a more relaxed view of the social life and customs of the residents. “They have some curious customs there; among others, if a man makes a bad joke they kill him. I can’t speak from experience on that point, because I never lectured there. I suppose if I had I should not be lecturing here.”

And a moment he used to great effect – his disavowal of the contemporary existence of cannibalism on the islands — “In other cities I usually illustrate cannibalism on the stage,” he admitted, “but being a stranger here I don’t feel at liberty to ask favors, but still, if anyone in the audience would lend me an infant, I will go on with the show.”

The talk was a huge success, so much so that in February 1873 he delivered his lecture on the Sandwich Islands at Steinway Hall for the benefit of the Mercantile Library Association. Steinway Hall was the same venue in which Twain heard Dicken’s American lectures while in New York as a special correspondent for the San Francisco Alta California newspaper in January 1868.

The New York Times reviewer noted that Twain “kept the audience convulsed with laughter…. His attitudes, gestures, and looks, even his very silence were provocative of mirth.” In this handbill announcing his New York lecture, Twain supplied the poster’s fictional editorial comments: “The most stupid lecture we ever heard;” “Twain is the homeliest man living;” “His lecture is a tissue of lies;” and, finally, a positive quote from the mythical Sandwich Islands Daily Express, offering up a cannibalistic appreciation of his performance!

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.