CBS news anchor Walter Cronkite reporting on the 1980 presidential election. Photo: Bernard Gotfryd. Prints and Photographs Division.

The photographs of Bernard Gotfryd, now free for anyone to use from the Library’s collections, are a remarkable resource of late 20th-century American pop-culture and political life, as he was a Newsweek staff photographer based in New York for three decades.

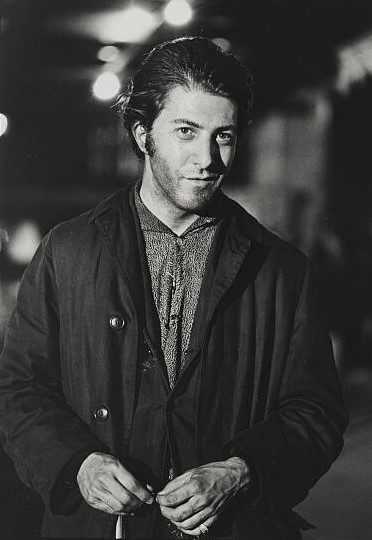

In his work, you’ll find film stars such as Dustin Hoffman on the set of “Midnight Cowboy,” novelists, painters, singers and songwriters, politicians at podiums and any number of passionate people at street protests. Gotfryd, who died in 2016 at the age of 92, left the bulk of his photographs to the Library and designated that his copyright should expire at his death.

Gotfryd was a Holocaust survivor. The Germans overran his Polish hometown of Radom days after World War II started. Late in life, he wrote and spoke eloquently about the horrors of those years, touching thousands of listeners and readers. His 1990 book of autobiographical sketches, “Anton the Dove Fancier and Other Tales of the Holocaust,” was written after Newsweek assigned him to photograph fellow Holocaust survivors at a White House ceremony, then sent him back to Poland for the first time since the war to cover a trip by Pope John Paul II, a fellow Pole, to their home country.

”It was a very emotional time, and the memories flooded my mind more than ever,” he told The New York Times in a 1990 article, ”And I remembered my mother, the day she was being deported to the death camp, begging me to stay alive so that one day I could tell the world what the Nazis were doing. When I returned from Poland, I knew that day had come.”

Both his parents and grandmother were killed by the Nazis, as were the vast majority of the 33,000 Jews in Radom. Gotfryd worked as a teenage photo-lab apprentice in the Radom Ghetto for four terrifying years. People were shot, hanged, tortured, dragged off to death camps. He saw pictures of all these, as Nazi officers brought pictures of atrocities to his lab to be developed. He leaked copies of those to Alexandra, a young woman in the Polish Resistance, where they were widely circulated. She was killed in the Warsaw Uprising; he was caught and sent to Majdanek, a forced-labor and concentration camp, and then to a succession of five others before being liberated by American troops in May 1945.

“People entered the showers, but never came back,” he told students at St. John’s University in 2007. “I imagined that this is what hell looked liked.”

He was just 21 when he immigrated to the United States, joined the Army as a combat photographer, and eventually settled in the New York borough of Queens. He married Gina, a fellow death-camp survivor whom he met in New York. They had children and he settled into a job at Newsweek.

After he left the magazine 30 years later, he wrote “Anton” and other books about the Holocaust. He published a collection of his photographs, “Intimate Eye: Portraits by Bernard Gotfryd,” in 2006.

Dustin Hoffman on the set of “Midnight Cowboy.” 1968. Photo: Bernard Gotfryd. Prints and Photographs Division.

Much of his professional photography is now at the Library, with scans of 8,803 color slides now online. Due to his generosity, they may be used by anyone, free of all copyright restrictions. More than 11,000 of his black-and-white photographs are available through contact sheets and prints that can be viewed by visiting the Prints & Photographs Reading Room. (Other parts of his papers are held by the New-York Historical Society Library & Museum and the Hoover Institution.)

Gotfryd was a working photojournalist often limited by time and availability with his subjects, resulting in a clear and straightforward style, devoid of pretense, almost always using natural light. One can see the practicality of how he learned his craft. This captures his famous subjects without the artifice of elaborate photo shoots. They look like regular people.

His photograph of Walter Cronkite on the set of CBS News reporting the 1980 election (above), is an excellent matching of photographer and subject – both men practiced their craft in an unadorned manner that belied the technique behind it. There’s the U.S. map looming behind Cronkite, framing the national story against the smaller man narrating it. Today, it’s a postcard from another time; an era when people trusted network television anchors, when cable television was still just a novelty, when the internet and cell phones did not exist. There was Walter Cronkite telling you that was the way it was on this particular day and that was it.

Night falls on Manhattan. Photo: Bernard Gotfryd, 1983. Prints and Photographs Division.

Another image to which time has lent a pathos – his lovely twilight photograph of the Gotham skyline, the Twin Towers serene and majestic in the dusk, the shadows already deep across the canyons of downtown.

But I think my favorite of the lot is a simple picture of children he took on that decisive trip to Poland. It was June 1983, nearly four decades since he’d left the horrors of that place, and we know from the books that followed how deeply this trip affected him. Most of the pictures are journalistic images of the pope, the huge processions that greeted him and so on.

Polish kids waiting for Pope John Paul II in Katowice, Poland, 1983. Photo: Bernard Gotfryd. Prints and Photographs Division.

But here, he stops and turns his camera to the side. These are five girls, in traditional dress, perhaps for part of one parade or another, waiting along with two adults (chaperones?) for Pope John Paul II. Four are chatting and giggling. One is yawning. You can feel the sense of belonging, of nostalgia, that makes a man of nearly 60 turn his camera this way and see the humor, the fondness in it.

Still, it could not have felt like his place in the world any longer. There were about three million Jews in Poland before World War II; about 85 percent were killed during the Holocaust. Survivors were subject to occasional pogroms, causing more to flee. After a nationwide anti-Semitic government crackdown in 1968, some 13,000 Jews left the country in the next few years, roughly half of the nation’s already decimated Jewish population.

By the time of Gotfryd’s visit, there were only about 10,000 Jews in the nation. How it must have felt, this sense of alienation amid the nostalgia of home. It’s the kind of thing he wrote about until the end of his life, and captured in this deceptively simple image.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.