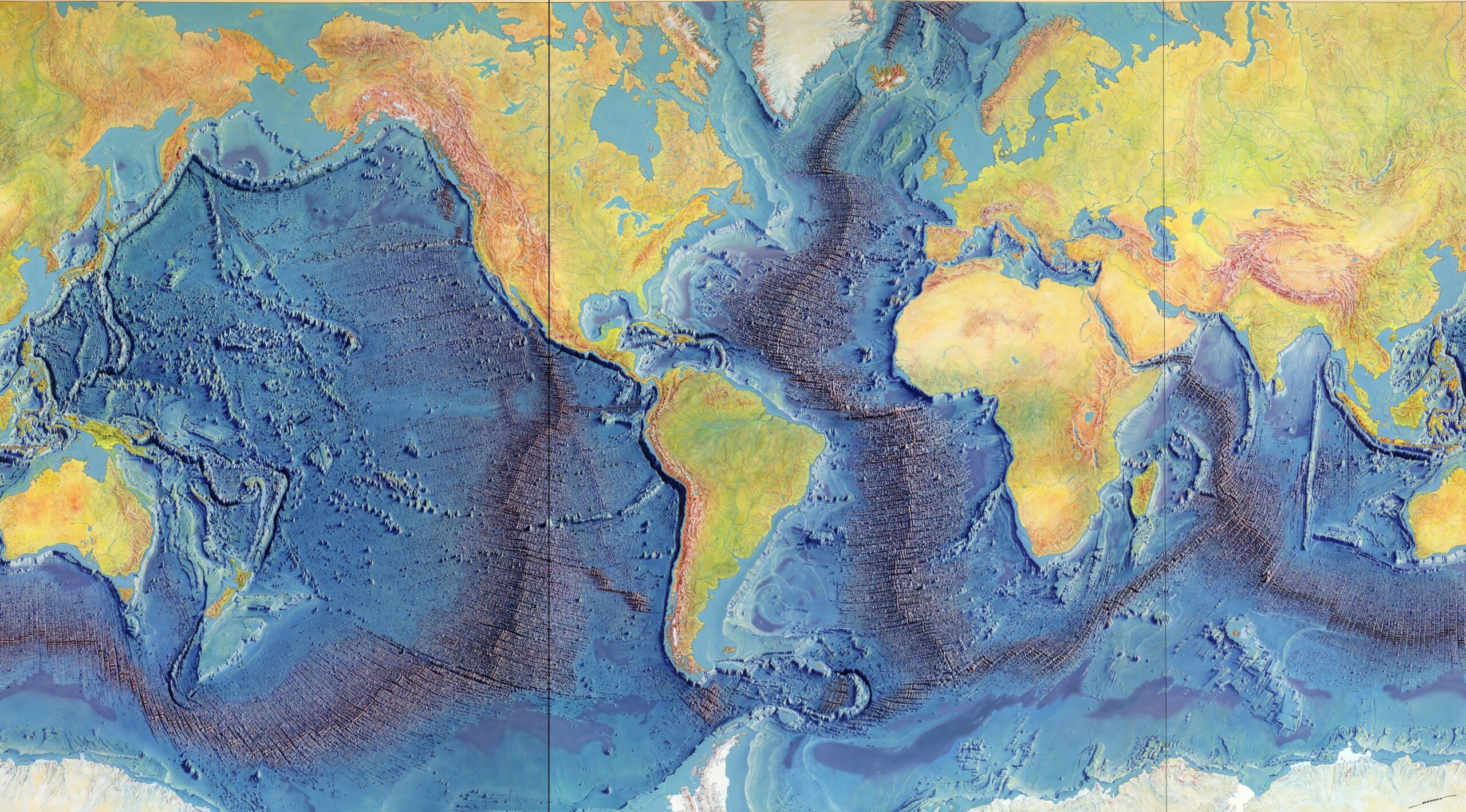

Heinrich Berann’s 1977 painting of the Heezen-Tharp “World Ocean Floor” map, a landmark in cartography. Geography and Map Division.

Mike Klein wrote a short piece for the Library of Congress Magazine’s July/August issue on the Heezen-Tharp map, pictured above. That article has been expanded here.

Marie Tharp was well-suited to the task of interpreting the texture and rhythm of the Earth’s surface, including the ocean floor — a space almost entirely unknown to humans, even after they began sailing the seas. A scientist, she had a background in mathematics, music, petroleum geology and cartography.

But she was a professional woman in the American mid-century in a field overwhelmingly dominated by men. She played a major role in one of cartography’s greatest achievements, mapping the sea floor for the first time in history, documenting a vast mountain range in the Atlantic Ocean. The maps she and her longtime collaborator, Bruce Heezen created then verified the theory of continental drift — the idea that the Earth’s continents shifted across the ocean bed due to the movement of tectonic plates. Continental drift is now fundamental to understanding how our planet came to be.

“It was a once-in-a-lifetime—a once-in-the-history-of-the-world—opportunity for anyone, but especially for a woman in the 1940s,” she wrote in a 1999 essay.

Tharp donated the papers of their research to the Library in 1995, then helped Library staff arrange the tens of thousands of items for future researchers. It is by far the largest manuscript/research collection in the Geography and Map Division, comprising maps, journals, research papers, letters, correspondence and geologic and cartographic data. It culminates in the depiction of the map in the painting above, the Heezen-Tharp “World Ocean Floor” map. It is still in use today and documents the 40,000-mile undersea mountain ranges that are critical to understanding how and why the Earth’s continents came to be where they are.

This collection is part of a larger archival project that documents some of the pioneering geographers of the 20th century, include Roger Tomlinson, one of the primary developers of the Geographical Information System (GIS), and John P. Snyder, who worked on the mathematics that enables mapping from space.

“Tharp’s work certainly provided evidence and weight to the theory of plate tectonics, but her work is really about seafloor spreading, which occurs at the mid-ocean ridges that she was the first to map,” says Paulette Hasier, chief of the division.

Marie Tharp with James Billington, former Librarian of Congress. Photo: Rachel Evans.

Tharp’s role as a top-tier female scientist who largely worked behind the scenes might prompt comparisons to the women at NASA’s space program in the 1960s, as featured in the book and film, “Hidden Figures.” But Hasier says the better comparison would be to the “Harvard Computers,” female scientists who worked at the Harvard Observatory in the early 20th century. Astronomers such as Annie Jump Cannon, Williamina Fleming and Florence Cushman helped develop and codify a classification system for some 300,000 stars, thus rendering the universe more of a known entity.

“Tharp, like these women, had a talent for visualizing data, something we take for granted today but required real geometric intuition before the widespread use of computers,” Hasier said.

Before Heezen and Tharp’s work, maps of the world showed three-fourths of it — the oceans — to be a flat blue surface. Sailors knew of reefs, channels and sand bars, of course, but not much else of what lay further below. Geologists had only a vague idea of the depths, but it was largely presumed to be flat and featureless.

“I think our maps contributed to a revolution in geological thinking, which in some ways compares to the Copernican revolution,” she wrote in an essay included in “Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University: Twelve Perspectives on the First Fifty Years 1949 – 1999.” “Scientists and the general public got their first relatively realistic image of a vast part of the planet that they could never see.”

In many ways, she had been working her entire life to make such discoveries.

Born in Ypsilanti, Michigan, in 1920, Tharp grew up moving to place to place, as her father was a soil surveyor for the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The family moved seasonally to follow his work, a peripatetic life in which she attended more than two dozen schools by the time she graduated high school. It left her, she later said, with a residual awareness of land, soil and the way the Earth is shaped.

Her father’s mantra: “When you find your life’s work, make sure it is something you can do, and most important, something you like to do.” At Ohio University, she didn’t find much she liked that women were allowed to do. The outbreak of World War II provided a break in the patriarchal system, as men were called away to war. In their absence, women took on many roles in the workplace they had not before. At the University of Michigan’s geology department, the staff began to allow female students. In 1943, Tharp was one of 10 young women who enrolled.

This led to unfulfilling work in the petroleum industry, which led to an unfulfilling math degree from the University of Tulsa, which led to an unfulfilling proposed job the American Museum of Natural History in New York, which, finally, led to a job at Columbia University’s Lamont Geological Observatory (now the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory). There, she soon met Bruce Heezen, another bright young star, with whom she would work for the next quarter century. The partnership was necessary, as women were not allowed on sea-faring research ships at the time. For years, while he gathered data at sea, she developed the data on maps back at the lab.

They began compiling thousands of files of data about the ocean floor (mostly sonar readings from U.S. Navy ships). The sonar soundings were rough, incomplete, and taken at different international measuring standards. Still, she began to map out data that showed a huge north-to-south mountain range underneath the Atlantic Ocean, bordered by a rift valley.

When she showed it to Heezen, he dismissed it as “girl talk” and scoffed that it looked “too much like continental drift,” then considered an outlandish theory.

“But I thought the rift valley was real and kept looking for it in all the data I could get,” she wrote. “If there were such a thing as continental drift, it seemed logical that something like a mid-ocean rift valley might be involved. The valley would form where new material came up from deep inside the Earth, splitting the mid-ocean ridge in two and pushing the sides apart.”

By the 1970s, as their work progressed, after they had charted the locations of tens of thousands of undersea earthquakes, and as their findings were collaborated by other scientists from around the world, the Mid-Atlantic Ridge became an obvious part of an undersea mountain range that stretched around the world.

The pair produced maps of individual oceans in partnership with National Geographic that culminated in the iconic worldwide panorama above in 1977, painted by Austrian artist Heinrich Berann. Ironically, Heezen died of a heart attack on a research cruise just a few months before the map’s publication.

She summed it all up this way:

“I worked in the background for most of my career as a scientist, but I have absolutely no resentments. I thought I was lucky to have a job that was so interesting. Establishing the rift valley and the mid-ocean ridge that went all the way around the world for 40,000 miles—that was something important. You could only do that once. You can’t find anything bigger than that, at least on this planet.”

Subscribe to the blog — it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.