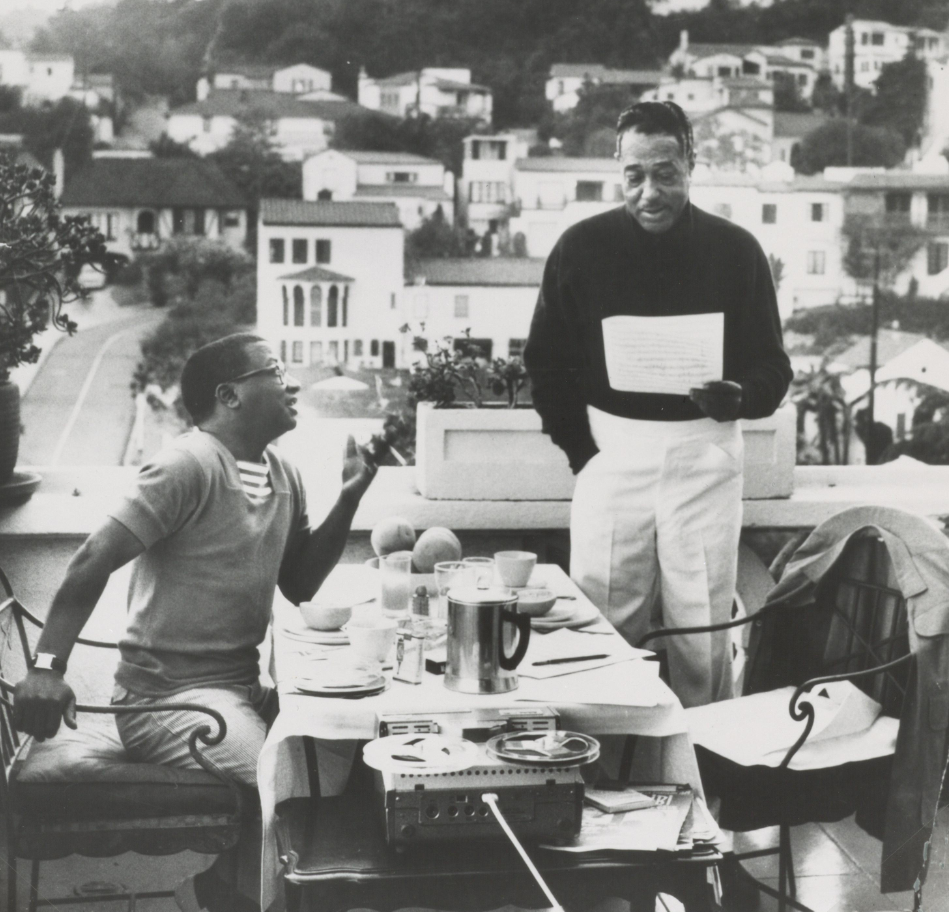

Billy Strayhorn and Duke Ellington. Photo: Unknown. Music Division.

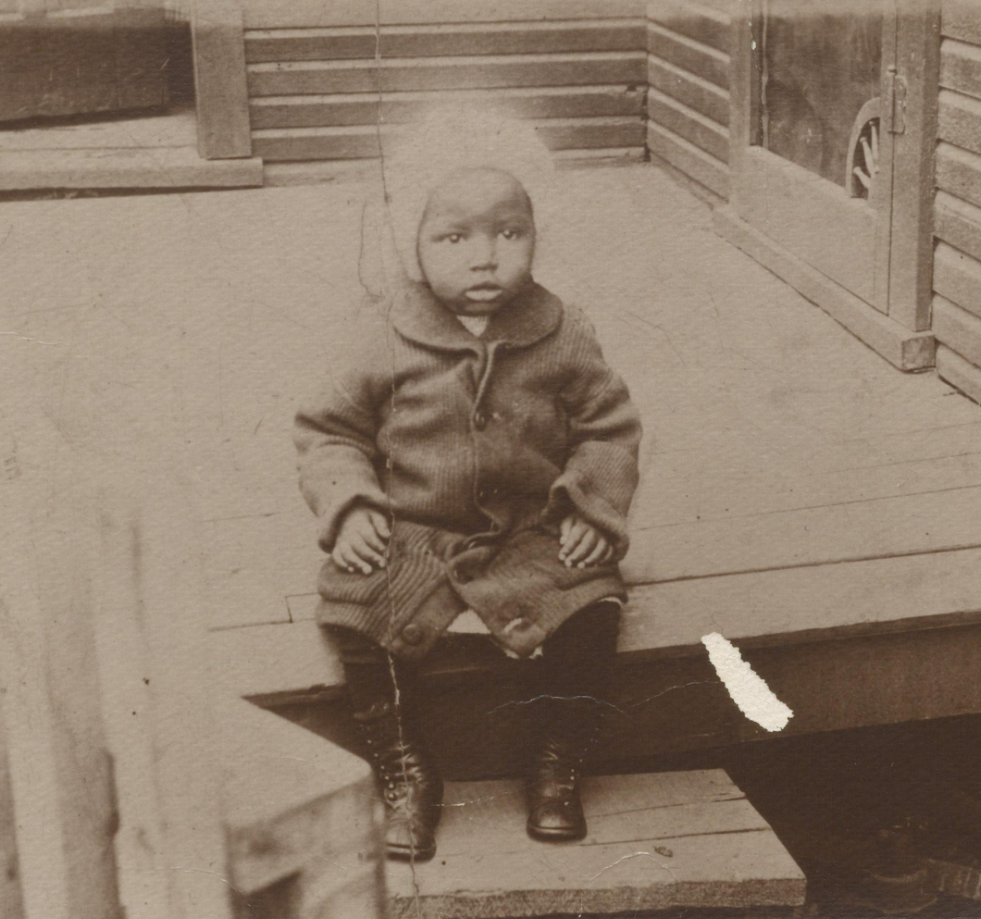

It was just a few years into the 20th century. Times were impossibly hard for a young Black couple in Dayton, Ohio. Two of their three children died in infancy. So on Nov. 29, 1915, when Lillian Strayhorn gave birth to another small and sickly child, she and her husband, James, didn’t bother to name him. They didn’t think he’d live long enough. They just put “Baby Boy Strayhorn” on his birth certificate.

Eventually, though, as Duke Ellington famously put it, “his mother called him Bill.”

Billy Strayhorn’s unlikely rise from childhood sickness and poverty to becoming one of the greatest names in 20th-century American music — he was the composer, arranger and songwriter for Ellington’s orchestra for three decades — is captured in his papers at the Library. The 17,000 items, including music manuscripts, letters, photographs, scrapbooks and business contracts, were brought to the Library by his family in 2018.

Strayhorn as a child. Family photo. Music Division.

Strayhorn wrote the iconic “Lush Life,” about the darker seductions of the jazz life, when he was a teenager. He wrote “Take the ‘A’ Train” at 24, just after joining Ellington’s band. He wrote “Chelsea Bridge.” “A Flower Is a Lovesome Thing.” “Day Dream.” “Rain Check.” “After All.” His style and Ellington’s so overlapped that scholars have a hard time deciding where one ended and the other began. Ellington agreed. “Billy Strayhorn was my right arm, my left arm, all the eyes in the back of my head,” he wrote in his memoir.

He was short, small, bespectacled, neatly dressed and fun to be around. He was a terrific vocal coach. Lena Horne absolutely adored him. “Ever up and onward!” was his motto. His nickname was “Sweat Pea” or “Strays.” He drank. He smoked. He was friends with everybody. He was openly gay in an era when that was all but impossible.

He died of esophageal cancer in 1967. One of his last pieces was “Blood Count,” about his cancer’s deadly progression. When he left one hospital a few weeks before his death, his nurse thanked him for his “extended hand of encouragement” to her. “I … hope that the power of God’s Blessings and protection will be your daily experience,” she wrote.

He was 51 when they buried him.

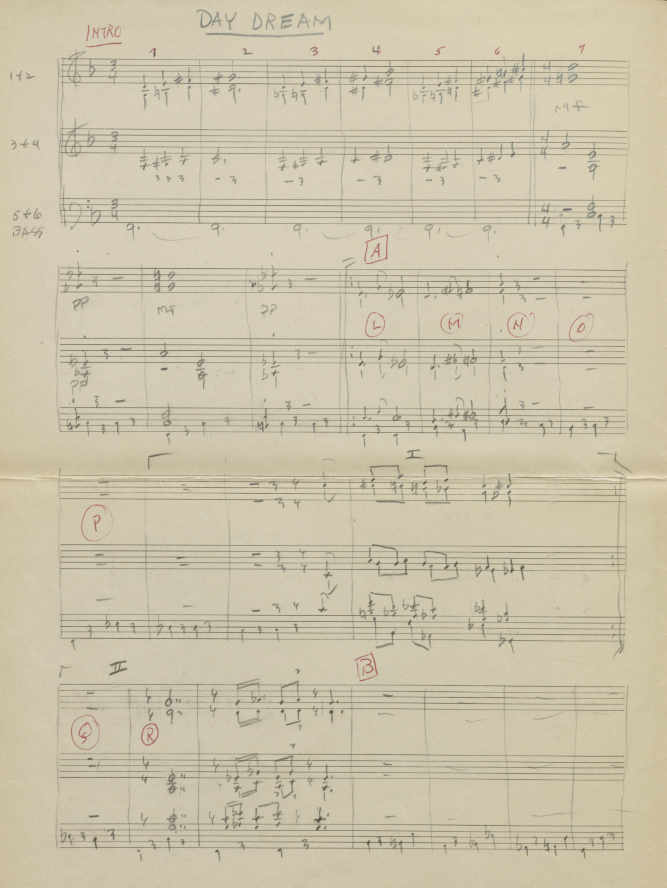

Strayhorn’s hand-written arrangement of “Day Dream.” Music Division.

His compositions are still “harmonically and structurally among the most sophisticated in jazz,” says the New Grove Dictionary of Jazz, a 1,200-page reference work. Pianist Donald Shirley, remembering the man for David Hajdu’s biography, “Lush Life,” put it this way: “Many composers in jazz are good at thinking vertically and horizontally, but Billy could write diagonals and curves and circles.”

Thanks to a number of posthumous recordings, biographies and retrospectives, he is perhaps more widely known today than during his lifetime. Billy Strayhorn Songs Inc., the company his family founded in 1997, works to protect his copyrights and cement his reputation.

“The Strayhorn legacy continues to move ‘Ever Up and Onward’ … as a new generation of artists are performing his works in recordings, on television, in film and on the stage,” said A. Alyce Claerbaut, Strayhorn’s niece and president of BSSI. “There has been increasing scholar study by jazz educators that has highlighted more of the singular genius that his writing and arrangement talents contributed to the Ellington Orchestra.”

Strayhorn and his mother, Lillian Young Strayhorn at a family reunion. Early 1950s. Family photo. Music Division.

Part of the magic of the Library is holding the works of people who have changed history and helped create the modern world. Their hand pressed the pen into the paper here. They scribbled in the margin there. Time moves at the speed of their pen across the paper.

It’s that way with Strayhorn’s papers. In a working copy of “Chelsea,” the musical notation is in pencil but he marks parts for the musicians in red ink: “Paul [Gonsalves],” “Proc [clarinetist Russell Procope]” and so on. Here is “Day Dream,” taking life before your eyes. The man held this very sheet of paper, the song just an idea in his head, concentrating, his hand sketching out chord progressions, until it was there, a finished thing. A ragged copy of “Lush Life,” which got wet somewhere along the way, marks out how the lyrics should be sung: “I used to vis-it all the ver-y gay places …”

It was the era when people wrote letters, and he was delightfully chatty and offhand.

On May 18, 1952, when he was 36 and a big star, he sent his parents a postcard from Yellowstone National Park. It showed a bear, standing on two feet, looking into a car window. “Dear Mom and Pop,” he wrote, “Would you like a nice bear for your living room? Mom, I tried to call on Mother’s Day but couldn’t get through … Love and Kisses, Bill.” From Hamburg, Germany, he wrote boxer Sugar Ray Robinson, after one of his fights: “We’re a long ways from home but we heard all about you. Congratulations! See you soon, Sweet Pea.”

The collection, like his music, is a charming and lovesome thing.

“Lush Life” sheet music that was sold commercially. Music Division.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox