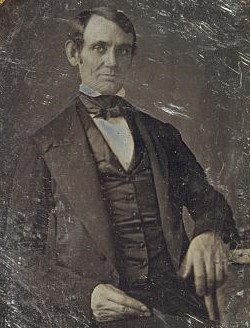

This 1846 or 1847 daguerreotype is the earliest known photograph of Abraham Lincoln. He was 37 and a Congressman-elect from Illinois. Photo: Nicholas H. Shepherd. Prints and Photographs Division.

This is a guest post by Mark Dimunation, chief of the Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

Abraham Lincoln never really had a “back to school” moment, as the future president was raised on a farm and had less than a year of formal schooling. This didn’t mean he didn’t love learning, though. From an early age, he devoted intense effort to self-study through reading.

In 1831, when he was 22, Lincoln left his frontier home in southwestern Illinois for the bustling village of New Salem, Illinois. Over the next few years, he worked as a store clerk, dabbled in business, served as postmaster and engaged in a serious regimen of self-education. By today’s standards, he was old enough to be a college graduate, but still considered his education to be “defective.”

So, soon after arriving in New Salem, Lincoln contacted the local schoolmaster, Mentor Graham, about the availability of a proper grammar for his study. Graham apparently recommended Samuel Kirkham’s 1828 volume, “English Grammar in Familiar Lectures.”

This was an influential, all-in-one volume that went through many editions over the years. It was filled with rules of grammar and syntax, sentence structure, instructions on pronunciation and basic composition, as well as warnings against provincialisms, such as “ain’t” “izzent,” and “askst.” There was a guide to common but erroneous manners of speech (“Give me them there books”) paired with the the correct way (“Give me those books.”)

Lincoln’s copy of Kirkham’s “English Grammar.” Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

“This work is mainly designed as a Reading-Book for Schools,” the introduction read. “In the part of it, the principles of reading are developed and explained in a scientific and practical manner, and so familiarly illustrated in their application to practical examples as to enable even the juvenile mind very readily to comprehend their nature and character, their design and use, and thus to acquire that high degree of excellence, both, in reading and speaking, which all desire, but to which few attain.” (emphasis in the original.)

Lincoln definitely wanted to attain that “high degree of excellence.” When it turned out that the only available copy of “Grammar” in the area was at the farm of John Vance, some six miles out of town, Lincoln didn’t hesitate. After the 12-mile round trip, and a few chores to help him earn the book, Lincoln returned home with his prized possession. It is the earliest book known to have been in Lincoln’s possession and is now in the Library’s Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

It was noted that Lincoln always had the book with him. He would later remark that it was his study of grammar that shaped his success and later gave voice to his eloquent speeches. Most likely he had it in hand one day when he acted on behalf of Denton Offutt, the owner of the general store at which he clerked. He was handling a receipt between James Rutledge and David Nelson. Today, that receipt is still attached to the inside front cover of the book.

Lincoln’s signature on the Offutt receipt. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

It was while working at Offutt’s store that Lincoln is said to have accidentally overcharged a customer. At Offutt’s insistence, Lincoln traveled the many miles to make amends for the error, earning him the sobriquet “Honest Abe.”

Meanwhile, that receipt is of more than just passing interest. The first party of the receipt, Rutledge, owned the local tavern, and his daughter, Anne, stayed with him. One version of this story, most likely apocryphal, is that Abe first became well acquainted with Anne in 1833 at her father’s tavern. Although she was engaged, the long absence of her intended freed Anne to eventually fall in love with young mister Lincoln. A promise was made to marry once she was released from her commitment.

Whatever the actual circumstances, they were on such good terms that Abe wrote on the title page: “Anne M. Rutledge is now learning grammar.” Whether this was a sweet double entendre between two young lovers, or just a polite inscription between friends, remains a matter of conjecture.

But more was not to come. Typhoid fever swept through New Salem in the late summer of 1835. Anne died of complications of the disease on August 25 — 186 years ago this week. Lincoln is said to have slid into a deep, dark depression. He eventually recovered, went on to work as a lawyer, and eventually married Mary Todd Lincoln seven years later.

The lessons he learned from Kirkham’s “English Grammar” stayed with him and helped him give the nation some of the most memorable speeches in its history.

Lincoln wrote “Anne M. Rutledge is now learning grammar” on the title page of his copy of Kelsey’s “Grammar.” Rare Book and Special Collections division.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox