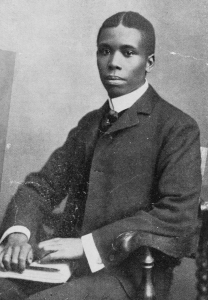

Paul Laurence Dunbar

Poet Maya Angelou’s debut memoir, “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings,” is her most famous work. The coming-of-age story has influenced writers and touched millions of people. Yet its title is not original to Angelou: She borrowed it from a poem by Paul Laurence Dunbar that he composed, at least in part, in response to his employment at the Library of Congress.

A new documentary by Frederick Lewis of Ohio University explores Dunbar’s poetry and life, including his stint at the Library. The film will be screened on Feb. 8 at 2 p.m. in the Mumford Room of the Library’s Madison Building. The Daniel A.P. Murray African American Cultural Association at the Library and its Moving Image Section are sponsoring the screening in recognition of Black History Month.

Here Lewis answers a few questions about Dunbar and the documentary.

Who was Paul Laurence Dunbar?

He was born to former slaves in 1872 in Dayton, Ohio, where he was boyhood friends with Orville Wright. The Wright brothers — Orville and Wilbur — had built their own printing press, and they helped Dunbar publish a short-lived newspaper for Dayton’s African American population when Dunbar was still in high school. The only African American in his class, he became editor of the school newspaper and was elected president of the literary club. The Dayton Herald was already publishing his poems. Yet upon Dunbar’s graduation, racism kicked in, and the only work he could find was as a janitor. For several years, he worked as an elevator boy in a downtown office building.

What made you want to create a film about Dunbar?

I teach documentary studies and production at Ohio University, and I was approached by a colleague who had secured funds from the state humanities committee to get the project started. As a former English major, I was somewhat familiar with Dunbar, having read a few of his poems in my American literature class. As the project unfolded, however, I began to realize how little I actually knew about him, how rich his brief life had been and how much archival material exists. As a filmmaker, I’m especially drawn to projects that allow me to delve deeply into archives to search for photos, old film clips and ephemera.

Frederick Lewis in his editing suite. An image from the Dunbar documentary appears on the screen behind him. Photo: Sam Girton.

How did Dunbar come to work at the Library of Congress?

In 1897, Dunbar’s book, “Majors and Minors,” was reviewed by literary lion William Dean Howells, after which Dunbar embarked on a reading tour of England. Financially, the trip was a disaster, and Dunbar returned home in need of work. Robert Ingersoll, a well-known orator, helped Dunbar secure a position at the Library as an attendant. He retrieved and reshelved medical and scientific volumes from the Library’s musty stacks.

The Library’s new home — now the Thomas Jefferson Building — had just opened, and Dunbar became the first poet to give a reading there, in the Reading Room for the Blind.

How does the concept of a caged bird relate to his Library employment?

Understandably, Dunbar’s time as an elevator boy back in Dayton is often assumed to be the inspiration for his poem, “Sympathy,” which contains the line, “I know why the caged bird sings.” This was of course the line borrowed by Maya Angelou for her famous memoir.

A gilded elevator is indeed a kind of cage, but the poem was written years later, during Dunbar’s time in Washington, D.C. Dunbar’s wife, Alice, herself an accomplished writer, noted in an article written eight years after her husband’s premature death:

The iron grating of the book stacks … suggested to him the bars of a bird’s cage. … The torrid sun poured its rays down into the courtyard of the library and heated the iron grilling of the book stacks until they were like prison bars in more senses than one … and he understood how the bird felt when it beats its wings against the cage.

What research did you do in the Library’s collections?

The vast collection at the Library is the first place I go to when starting a new project. It is an absolute treasure trove. Although I use more than 550 photos and pieces of ephemera in the Dunbar documentary, drawn from more than 100 archives and private collections, the materials at the Library were absolutely critical. I haven’t done a tally, but I’m sure that I must have used more than 150 images from the Library, many of which helped me provide historical and geographical context. The librarians I worked with were excellent allies, always getting back to me with timely, thoughtful information about collections I needed to access.

Your film ties Dunbar to other individuals whose papers are at the Library. Can you elaborate?

As I mentioned, Orville Wright was a boyhood friend of Dunbar’s. I use several items from the Wright Brothers collection at the Library, including photos, letterhead from their bicycle shop and their celebratory telegram to their father on Dec. 17, 1903, after their first powered, controlled and sustained flight.

Mary Church Terrell and Dunbar met at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago and years later became next-door neighbors in LeDroit Park in D.C. Terrell recalled, “I can see Paul Dunbar beckoning me as I walked by, when he wanted to read me a poem which he had just written or when he wished to discuss a word or a subject on which he had not fully decided.”

At the time, Terrell was teaching at the M Street School, where her husband, Robert, was principal. The M Street School would later be renamed Paul Laurence Dunbar High School, in honor of their neighbor.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.