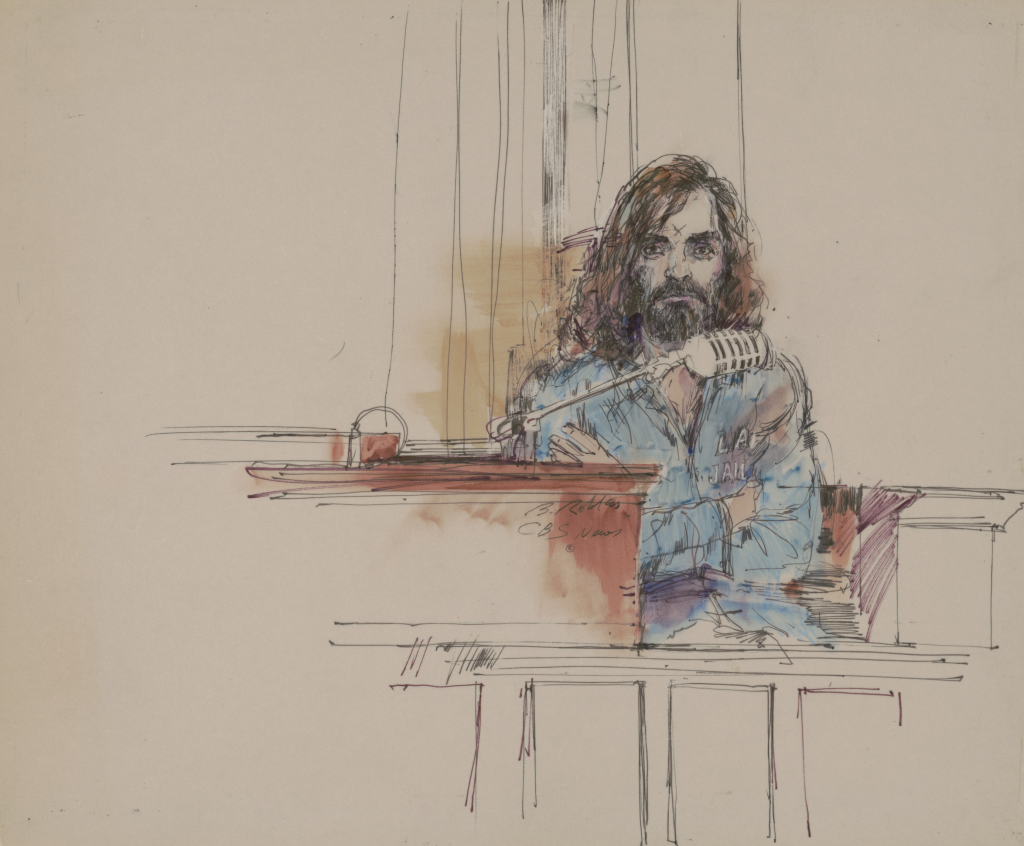

Manson on trial in Los Angeles. Sketch: William Robles. Thomas V. Girardi collection, Prints & Photographs Division.

This story is adapted from an upcoming issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

Charles Manson scarcely appears in “Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood,” the new Quentin Tarantino film. But the Manson family’s murderous home invasions on the nights of August 8 and 9, 1969, give the film its narrative tension, and Manson’s aura hangs over the entire film, as it should. The story of his band of hippies turned killers – mostly wayward young women with a penchant for drugs, sex and knives – has transfixed the nation for half a century, in a way that few other crimes ever have.

The slayings – seven people were butchered, including actress Sharon Tate, who was eight and a half months pregnant — were a horror show that brought the excesses of the decade into glittering focus. The nation, transfixed, looked at the killings and saw the larger society unraveling. Hippies, drugs, guns, celebrity, violence, racism, counter-culture revolution. It all blew up into the madness of a man who wanted to ignite an apocalyptic race war by killing rich white people and framing black people for it.

Front page of Los Angeles Times, Dec. 6, 1969, with headlines designed to generate street sales.

The Manson murders, Joan Didion famously wrote, ended the ‘60s. “Helter Skelter,” prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi’s frightening book about the killings, is still the best-selling true-crime book in U.S. history. All three of Manson’s female co-defendants were sentenced to death, likely the most women condemned to die in one incident in North American jurisprudence since the Salem witch trials in 1692. (All the death sentences in the case, including Manson’s, were later commuted to life in prison following a U.S. Supreme Court decision.)

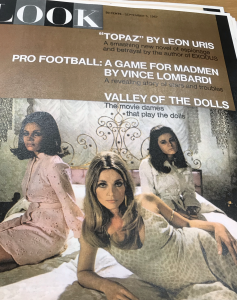

Sharon Tate, on the cover of Look magazine, Sept. 5, 1967. Look Collection, Prints & Photographs Division.

As the books, pop songs, films, documentaries and based-on novels blossomed over the years – Tarantino’s is only the latest in a very long list — Manson became the primogenitor of the “killer with something to say” trope, the idea that there’s this darkly intelligent madman who’s onto something about the quivering underbelly of the American dream. Like he was “The Joker” from Batman, brought to life. Reporters flocked to his jail cell for interviews, even before his trial. He was profiled on the cover of Rolling Stone. His image — greasy black hair, grungy beard, the “X” he cut into his forehead before his trial — was emblazoned on T-shirts and posters. Guns N’ Roses recorded one of his songs. Trent Reznor of Nine Inch Nails made a music video in the house where Manson’s followers killed Tate and her friends. Rocker Marilyn Manson used the killer for half of his stage name.

“I am what you made of me and the mad dog devil killer fiend leper is a reflection of your society,” Manson said after his conviction. “Whatever the outcome of this madness that you call a fair trial or Christian justice, you can know this: In my mind’s eye my thoughts light fires in your cities.”

He died in prison in 2017, at age 83.

Manson’s hold on the national imagination is preserved in the Library in several ways – courtroom sketches, books, newspaper archives, recordings – the most notable of which is the iconic drawing by the legendary courtroom artist William Robles. Robles spent every day of the nine-month trial sitting a few feet away from Manson, who, as he remembers, “terrified people.” Once, when Robles accidentally knocked over his sketching materials, making a clatter, he looked up to see Manson suppressing a giggle, playfully running one index finger down the other: The “shame on you” gesture.

“I could see how people were attracted to him,” Robles said in a recent interview. “He had an appeal, a warmth.”

It’s not as crazy a contradiction as it sounds.

Since the dawn of time, human beings have killed one another, often for reasons that can neither be clearly articulated nor understood, and this violent mystery goes to the heart of human nature. Who are we? What are our ultimate taboos, and how do we respond when these are violated? Crime, writ small or large, can therefore become a shorthand, a brutal slash of insight, into the society that spawns it.

The first lines of Homer’s “The Iliad” — the foundational epic of Western literature, composed about 2,800 years ago – describe the murderous “anger of Achilles” that sent many a brave soul “hurrying down to Hades.” The Biblical Book of Genesis, another cornerstone of Western culture, says that when the population of the Earth was four, Cain killed Abel, reducing it to three.

The Library’s holdings on the meanings of murder range from ancient manuscripts to Wild West ballads to most everything in between. Some of these reflect the low arts of the “penny bloods,” the wildly popular Victorian-era serial stories that presaged today’s tabloids. Others achieve the status of high art, such as Truman Capote’s “In Cold Blood,” the 1966 story of a multiple murder in Kansas that helped create the true-crime-as-literature-and-social-commentary genre.

Harry Truman, then a U.S. Senator from Missouri, lets U.S. Vice President John Nance Garner handle Jesse James’ guns. Feb. 17, 1938. Photo: Harris & Ewing. Prints & Photographs Division.

The roots of this run deep in the American bloodstream. After the Civil War, the “Wild West” became a mythological landscape, a place where murder, blood and cruelty became a romantic notion. Jesse James, a Missouri-born bank robber and killer, became a cultural icon. Nearly a century after James was gunned down, President Harry Truman, a fellow Missourian, acquired his pistols and playfully posed with them – murder weapons as presidential guffaws.

“It’s always been an American theme to make heroes out of the criminals,” Johnny Cash, who himself made a career from songs of outlaws and prisons, told Rolling Stone in 2000. “Right or wrong, we’ve always done it.”

But it was only after Capote’s lyrical tale of murder in rural Kansas that Americans began seeing non-fiction literature and serious art as appropriate forums with which to address the nation’s violent culture without the gauze of fiction. The “New Journalism” Capote and others practiced on crime reporting became so influential that, today, we take it for granted. Pulitzer Prizes, National Book Awards, Academy Awards – all have all been given to tales of true crime. In 2016, ESPN Films described “O.J.: Made in America,” its Academy Award-winning, eight-hour documentary about the 1990s O.J. Simpson murder trial as “the defining cultural tale of modern America – a saga of race, celebrity, media, violence, and the criminal justice system.”

They might well have been describing the Manson case half a century earlier. Robert Kirsch, the L.A. Times book editor, reviewing “Helter-Skelter” upon publication, seized on the crime’s significance. The book, and others like it, he wrote, were attempting to understand the frightening era in which they were living: “To accept these (killings) as simply symptoms of the malaise of the times,” he wrote, “is to abandon the obligations of civilization to rationally address even the most irrational and fearful events.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.