Exploration into the unknown — when much of the world’s surface was not accurately mapped — is the theme of this month’s edition of the Library’s Free to Use and Reuse sets of copyright-free material. The collection is an eye-opening reminder that much of the globe was not recorded until late in the 19th century.

For example, California dreamin’ wasn’t a thing — or maybe, in fact, it was — in the mid-17th century, when European explorers were just getting a fix on what would become, three hundred years later, La La Land.

Joan Vinckeboons 1650 map of California. Geography and Map Division.

Joan Vinckeboons (aka Johannes Vingboons), a prominent Dutch mapmaker and artist in the 17th century, thought California was a large island off the coast of North America, much the same way England was a large island off the coast of Europe.

Spanish and Portuguese explorers had been traveling through Mexico and Central America for a century before the map was made, with Portugese-born João Rodrigues Cabrilho being the first to explore the coast of what is now California in 1542 and 1543, dropping anchor in San Diego Bay. They called it ”Alta California” and discovered that Native Americans had been living there for ages. Vinckeboons executed this map circa 1650, more than 100 years later, but still two decades before a permanent European settlement was established on the California coast, by which time they had learned that California was, in fact, not an island.

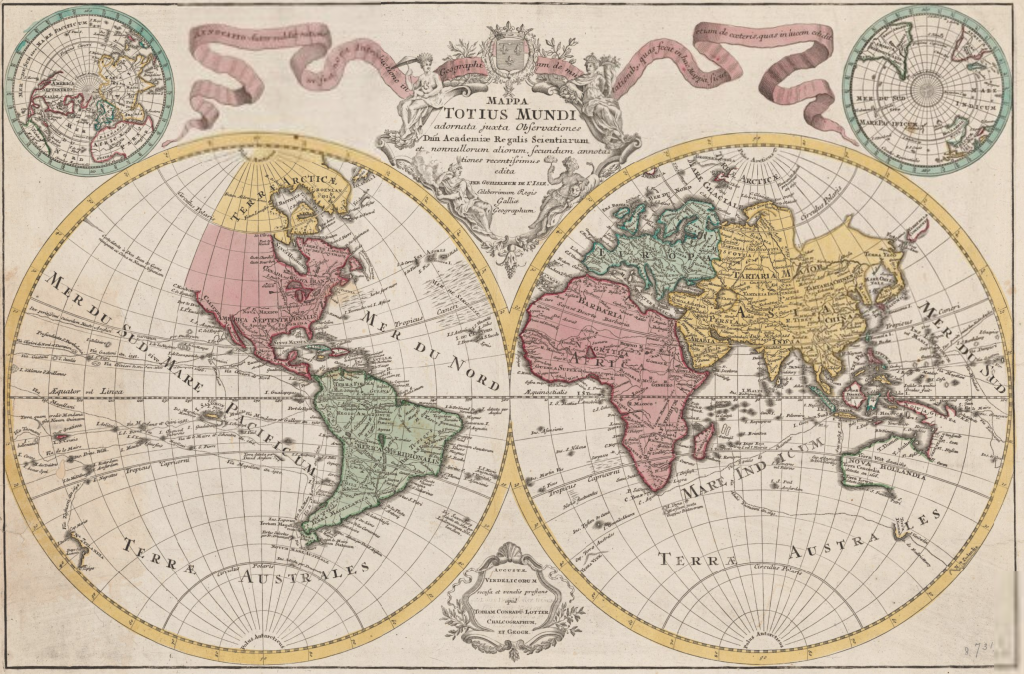

Still, by the early 18th century, the elite of Europe knew the planet’s broad, continental outlines, as seen in this map by one of the great cartographers of the era, France’s Guillaume de L’Isle.

“Mappa Totius Mundi,” by French cartographer Guillaume de L’Isle. Geography and Map Division.

You’ll notice that western part of North America is a squared-off blank, and that’s where our last map comes in, courtesy of the redoubtable team of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. Below is an 1803 map that they used in the planning stages of their voyage.

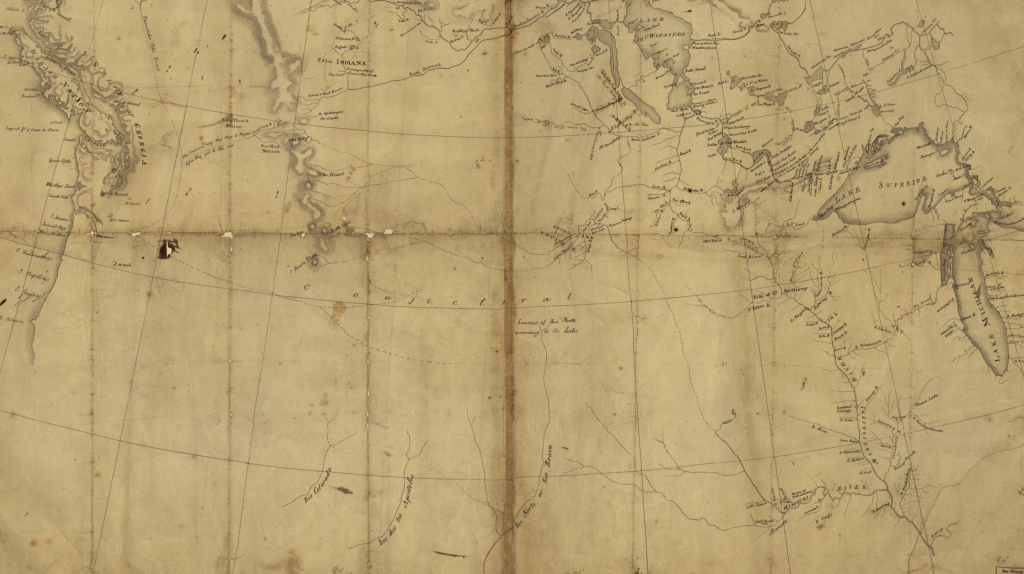

Lewis and Clark’s map of the west, circa 1803, just before they set out. Geography and Maps Division.

President Thomas Jefferson commissioned them to lead an expedition to explore the new Louisiana Purchase in 1804. The pair traversed 8,000 miles over three years, reaching the Pacific coast at present-day Astoria, Oregon, and made it back home, losing only one man in their original 45-member crew. (Sacagawea, their Shoshone MVP guide, survived the expedition, too.) Their explorations over the vast plains of the northwest, the Rockies and then on to the west coast, changed American history. This map, the work of U.S. War Department cartographer Nicholas King, was “the federal government’s first attempt to define the vast empire later purchased from Napoleon.” Lewis took it as far as Mandan Village, where they hunkered down for the first winter of the trek.

In this close-up, you can see some of Lewis’ notations in brown ink. This detail is from what is now Canada, with Lake Manitoba to the right. The upside-down writing in the center reads, “the river that calls.” That was the English translation of its Cree name, Catabuysepu, and it was said to be haunted by spirits that wailed during the night, according to the journals of fur traders who worked in the region during the era. Today, it is the Assiniboine River, named for another Native American tribe of the region.

Lake Manitoba, Canada, lies on the right of the map.

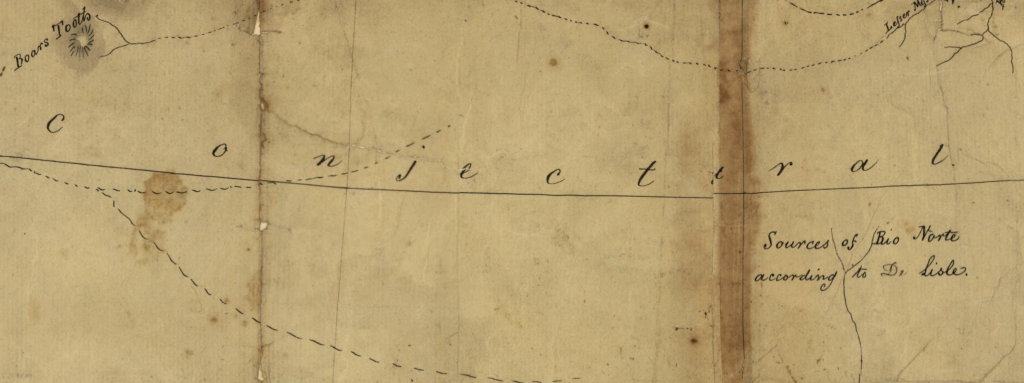

But, really, the most striking part of the map is one word spread across hundreds of miles of territory: “Conjectiral” (sic). The word lies along the 45th parallel, roughly the border between Montana and Wyoming, but includes, in its vastness, Oregon, Idaho, Nevada, Colorado, Utah, Nebraska, South Dakota and Kansas. The westernmost settlement on the southern side of the map lies in present day central Missouri.

The vastness of the unknown: “Conjectiral” (sic) on the early map of Lewis and Clark.

The territory, populated by dozens of tribes of Native Americans who did not need to conjecture about the landscape at all, would not be sectioned off into parts of the United States for another five decades or more. It was, at the time, still a land without fences.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.