This is another guest post by Giselle Aviles, the 2019 Archaeological Research Associate in the Geography and Map Division. It was first published on the Library’s Worlds Revealed by John Hessler. We’re republishing a slightly edited version here. As John noted in his original post: “She is delving into the treasures of the Jay I. Kislak Collection of the History and Archaeology of the Early Americas, undertaking an ethnographic analysis of Andean textiles and mesoamerican ceramics, tracing and unfolding their stories. She is a former Research Fellow of the Quai Branly Museum-Martine Aublet Foundation in Paris, and has conducted fieldwork in Puerto Rico, Haiti, Algeria, France, and Spain. She has come to the Library through the Hispanic National Internship Program sponsored by the Hispanic Association of Colleges and Universities (HACU).” How can I tell stories about ancient artifacts when their parts are scattered in different places in a library? I take the example of ethnographers: When they are doing fieldwork to decipher a given society, they study the general culture along with specific items, such as photographs, personal letters, official documents and historical archives. They’re always looking for an “Aha!” moment that offers a bit of unique insight.

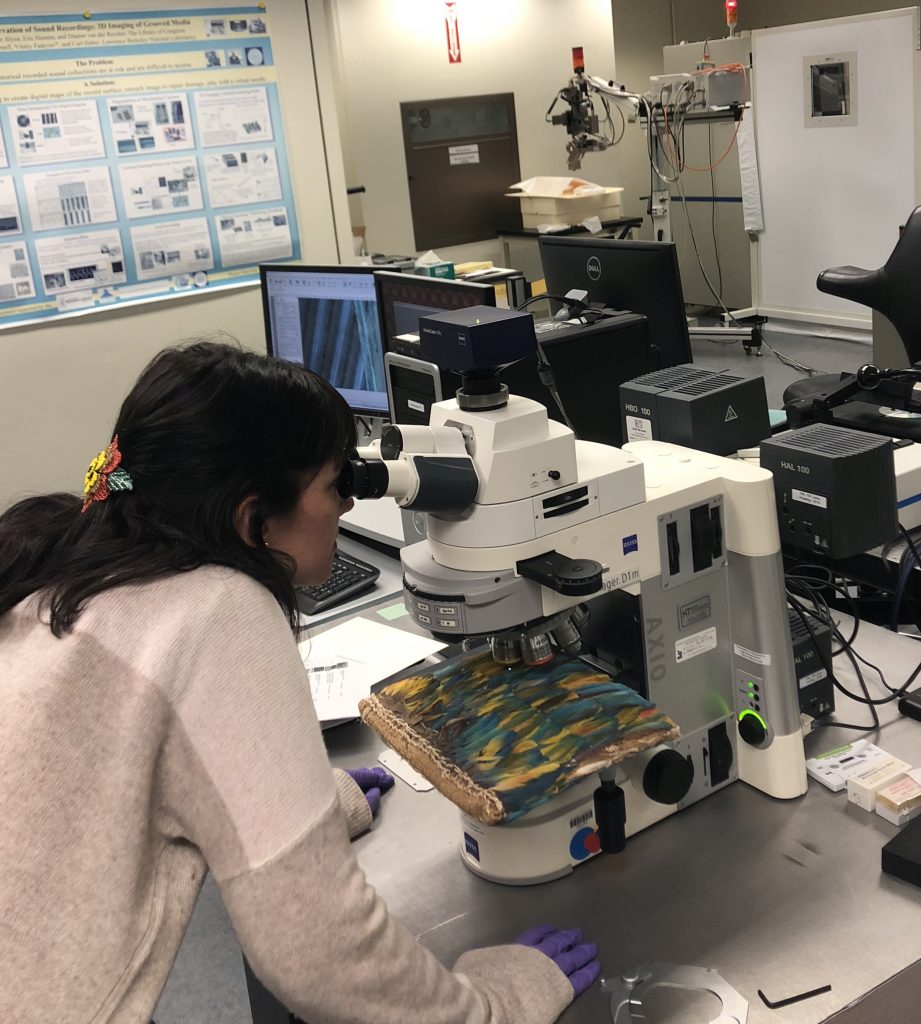

Giselle Aviles examining a miniature feather tunic from the Ica Valley of Peru, 12-13th century CE in the Preservation Research and Testing Division of the Library. William and Inger Ginsberg Collection, Library of Congress.

When I received the message that I was going to collaborate with John Hessler, the curator of the Jay I. Kislak Collection of the Archaeology and History of the Early Americas — which includes Pre-Colombian Peruvian textiles and Mayan ceramics — I couldn’t believe it. No longer would I be appreciating early American artifacts through the exhibit cases of a museum. I would be close to them, studying them, feeling them.

Photograph in UV light of the Ica Feather Tunic. Analysis by Tana Villafana, Senior Scientist in the Preservation Research Division, and Giselle Aviles, Archaeological Research Associate

It’s been thrilling. The Kislak collection encompasses, for example, a diversity of chuspas, a Quechua word for a hand-woven pouch used to carry coca leaves. When looking for the first time at the Peruvian textiles, donated by William and Inger Ginsberg, I found myself imagining the stories behind them. What conversations could have taken place? What social relationships would have developed? Did many families weave? Why did they chose those specific colors and patterns? Did a preferred location to weave exist, such as at home or a workshop? What would the weaver’s space be like while the textile was being thought through and produced?

My methodology over the next few months will be to grasp the symbols, colors, and feelings of objects in the Kislak Collection and relate them to other items in the library, such as rare books, manuscripts and maps. Working with archaeological artifacts in an ethnographic way is exciting, and there is not a single day when I don’t learn something new. I have the objects in front of me. I sit in the cold vault where the artifacts are temperature protected and, alone, I talk with them. How can an ancient life be thought about through a specific artifact? These are questions that I hope to ponder during my research time at the Library and discuss in my Gallery Talks in the Exploring the Early Americas Exhibit.

Maya Ceramic Vase with Animal Way Dancers. One of the many ceramic pieces being investigated by Giselle Aviles. Jay I. Kislak Collection, Library of Congress.