Harry Houdini, July 7, 1912. The crate will be sealed and lowered into New York Harbor; he’ll escape. Photo: Carl Dietz. Prints and Photographs Division.

This is a guest post by Amanda Zimmerman, a reference assistant in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division. Since we’re approaching Halloween, we thought we’d drop in on America’s most famous mystic and magician, Harry Houdini. This article was adapted from the Library of Congress Magazine.

One of the most recognizable figures of the 20th century, Harry Houdini — escape artist, debunker of frauds, delver into all things mysterious — spent a surprising amount of time in the company of the police. The Library has his collection in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division, and it is filled with marvelous things — just ask author, actor and magician Neal Patrick Harris, who visited the collection before his recent appearance here.

One thing that you’lff notice is that the self-proclaimed Handcuff King routinely issued challenges to law enforcement, claiming that no handcuffs or prison cells could hold him — stunts that made Houdini famous around the world and frequently brought him into contact with people on both sides of the law. He spent a lifetime studying the methods of the criminal element to understand how they duped the innocent and unsuspecting.

This insight resulted in law enforcement occasionally asking for Houdini’s help in solving crimes. On at least one occasion, Houdini received an official police pass allowing him to cross any police barriers in an active crime scene or investigation.

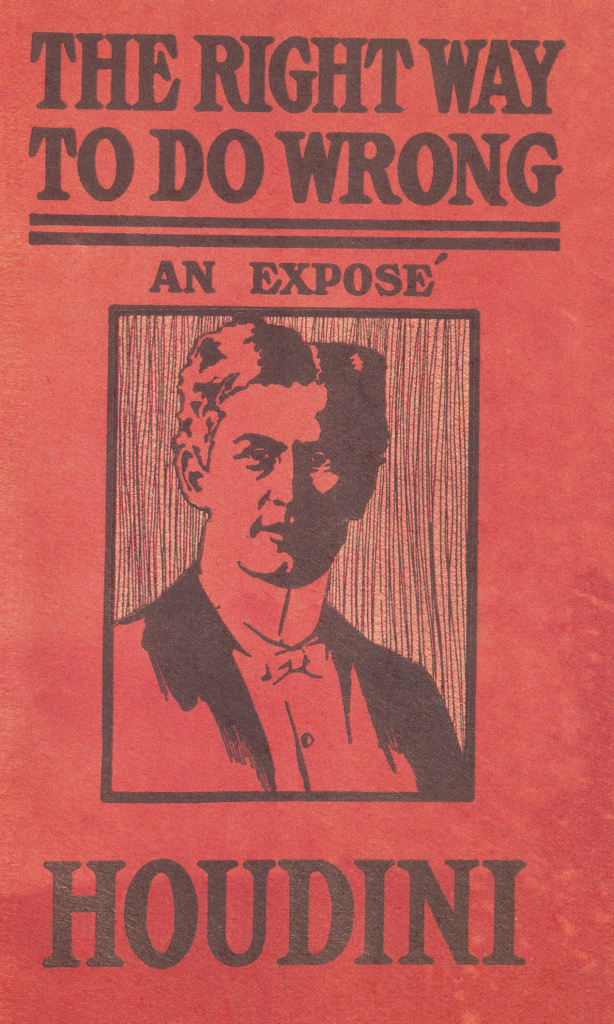

From the Harry Houdini Collection. Rare Books and Special Collections Division.

This unusual level of involvement with police matters allowed Houdini to amass a huge amount of information related to crime, fraud and general wrongdoing. In 1906, he gathered this information and published “The Right Way to Do Wrong: An Expose of Successful Criminals.”

In the preface, Houdini outlines his purpose: “I trust this book will … put you in a position where you will be less liable to fall a victim.” Each chapter explores various classes of criminals, from burglars and cracksmen to “healers” and humbugs, revealing the tricks they use to con their innocent prey. Houdini condemns the behavior of criminals but also claims they have the same “talents” as giants of business and finance — only with their energy and skills applied in the wrong direction.

The books were sold primarily at Houdini’s own performances, and rumors circulated when it was published that criminals snatched up as many copies as they could in an effort to protect their secrets (rumors now supposed to have been started by Houdini himself). Perhaps Houdini truly did hope to use his knowledge to inform and protect the innocent public; perhaps he also saw this as an opportunity to once again display his incomparability as the master of all that mystifies.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.