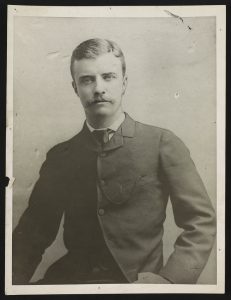

Theodore Roosevelt, 1884.

This is a guest post by Michelle Krowl, a historian in the Manuscript Division.

On Feb. 14, 1884, Theodore Roosevelt marked an X in his pocket diary, followed by the words, “The light has gone out of my life.” That morning his mother, Martha Roosevelt, died of typhoid fever. That same afternoon, in the same house, his wife, Alice Hathaway Lee Roosevelt, died of kidney disease, just two days after giving birth to their daughter. On another page, Roosevelt recalled his relationship with Alice, concluding, “For joy or for sorrow my life has now been lived out.” He was 25 years old.

Roosevelt’s life had really only begun, however, and his papers at the Library of Congress record his extraordinary public career through voluminous correspondence sent and received, speeches and executive orders, press releases and public statements, diaries and scrapbooks. The Theodore Roosevelt Papers, now available online, document the multifaceted and remarkable life led by America’s 26th president.

Roosevelt’s diary entry for Feb. 14, 1884.

T.R. entrusted his infant daughter to his sister Anna, and set off for the Dakota Territory. “Black care rarely sits behind a rider whose pace is fast enough,” Roosevelt later wrote. He exercised his grief by leading the strenuous life of a cattle rancher, and learned the politically useful skill of working toward a common goal with people from different backgrounds. “I got along excellently with everyone,” he wrote his son Ted in 1908. “I worked hard with them on the roundup.” Roosevelt’s western period also gave him a cowboy image, which political cartoonists used in years to come.

Roosevelt found happiness with his second wife, Edith, his children and public service. He served on the United States Civil Service Commission (1889–95), and then applied his abundant energy to the New York City Board of Police Commissioners (1895–97). There he honed skills that he employed for the rest of his career. He sought reform in the operation of the police force and went on “midnight rambles” to determine how many beat cops slept at their posts or engaged in corrupt activities. He cultivated the press to publicize his actions and learned from reporters like Jacob Riis about problems in the community. As the scrapbooks in the Roosevelt papers attest, T.R. made news as a police commissioner, and his prominent teeth and eyeglasses became symbols that forever more identified Roosevelt cartoons.

An 1895 cartoon depicts Roosevelt solely by way of his pince-nez glasses and his prominent teeth.

A 1900 cartoon also portrays Roosevelt by his glasses and his teeth.

Roosevelt followed his police work by serving as assistant secretary of the Navy, where he advocated Alfred T. Mahan’s principles of naval supremacy. When the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898, Roosevelt refused to miss his “crowded hour” of glory and organized the First Regiment, U.S. Volunteer Cavalry, better known as the “Rough Riders.” He parlayed his fame as the hero of San Juan Hill into election as governor of New York, telling his friend Cecil Spring Rice in November 1898, “I have played it in bull luck this summer. First, to get into the war; then to get out of it; then to get elected.”

Roosevelt flees the vice presidency in the cartoon “The Office Seeks the Man,” published in 1900.

Roosevelt, a Republican, continued his reformist and independent ways as governor, to the chagrin of his party’s establishment in New York. Political bosses hoped electing him vice president in 1900 would shelve him in a powerless position. Although he did not want the job, T.R. campaigned hard for President McKinley and reconciled himself to the end of his political ascent. In September 1901, however, an assassin’s bullet ended McKinley’s life, making Roosevelt president of the United States.

Roosevelt’s presidency is the best-known period of his political life, and it is documented extensively in his papers. Incoming correspondence captures the issues brought to Roosevelt’s attention, while letterpress copybooks record his voluminous output on subjects from coal strikes to conservation, from statues to socialism. Scrapbooks contain newspaper clippings on various aspects of the Roosevelt administration, and desk diaries reveal who met with the president on a daily basis.

An April 11, 1908, letter from Roosevelt to his son Archie in which Roosevelt describes punishing Archie’s brother Quentin for putting spitballs on portraits at the White House.

Throughout his political career, Roosevelt enjoyed another life as an author. He published historical works; wrote about his experiences as a rancher, hunter and explorer; and regularly contributed articles to periodicals such as “The Outlook.” T.R. even briefly tried to change the English language itself by promoting economical spelling, such as substituting “thoroly” for “thoroughly.” The experiment failed, but Roosevelt accepted good-natured ribbing from associates and continued using alternative spelling in his personal correspondence.

After leaving the presidency, T.R. went on safari in Africa, sending specimens to the Smithsonian Institution. He then toured Europe in 1910. After breaking with the Republican Party in 1912, he formed the Progressive or “Bull Moose” Party and ran unsuccessfully for president. He went to South America in 1913 on an expedition to explore an Amazon River tributary later named in his honor.

The outbreak of World War I brought Roosevelt back into the public arena as an ardent voice for American war preparedness. T.R. even offered to raise troops, but the Wilson administration rebuffed his offer. “I am a man of action,” Roosevelt wrote in June 1917, “and the President has refused to let me take part in this great contest as a man of action.”

Theodore Roosevelt, the man of war who also received a Nobel Peace Prize, died in his sleep on January 6, 1919.