Michael Ford’s work in 1970s Mississippi was the foundation of his new book.

Heat. Molasses. Wooden houses, tin roofs. Grist mills. Mules, ears twitching. Metal on iron. Ice falling into a glass. Screen door hinges. Wind in the oaks. Eight-track music from the truck. Long orange sunsets that hang in the sky, a gloaming that gives way to a deep, penetrating darkness ruled by crickets and cicadas and four-legged animals that move, unseen, in the woods.

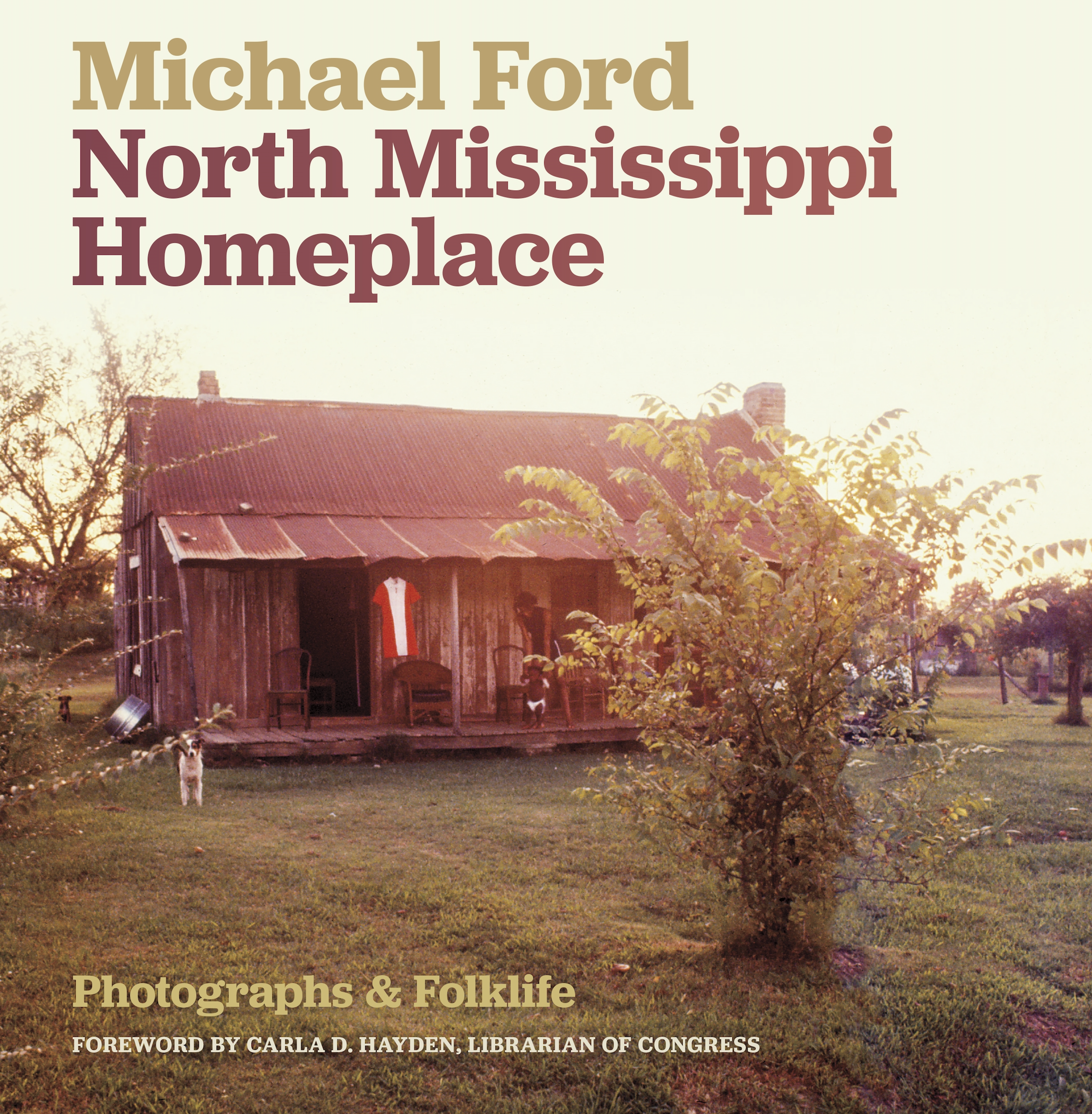

Northeast Mississippi’s hill country is a largely forgotten corner of the nation, peculiar in its mixing of Appalachian white culture and African American life more associated with the Delta on the western side of the state. It’s been one of Michael Ford’s artistic muses since the early 1970s, when he made “Homeplace,” a half-hour documentary that enshrined the place and time. A photographer and filmmaker, his subject was the vanishing culture of rural, agrarian America, where craftsmanship and self-reliance molded the shape of daily life. He was on point — one of the villages he filmed, Chulahoma, is now listed as an “extinct community,” and the general store he filmed and photographed there is long gone.

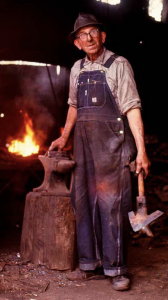

M.R. Hall. Photo: Michael Ford.

This bittersweet perspective informs “Northeast Mississippi Homeplace,” a book of Ford’s photography and writings published this month by the Library in association with the University of Georgia Press. It encapsulates Ford’s original work and a trip back to the same places a few years ago. The Library’s American Folklife Center acquired Ford’s Mississippi collection in 2014 — several hundred photographs, film reels, manuscripts and audio recordings — and the book grew out of that project.

North Mississippi “is a special place, a special part of America,” said Todd Harvey, a collections specialist in the AFC and curator of the Alan Lomax Collection, during a recent onstage conversation with Ford and Aimee Hess, the book’s editor. The conversation, part of the Botkin Lecture Series, was at the Whitthall Pavilion, and launched the book’s publication to a full house.

Ford grew up in the northeast, but took his young family to Mississippi in the early 1970s to work on an in-depth exploration of the folkways of one of the poorest places in America. He apprentinced himself to blacksmith Marion Randolph Hall, whose shop in Oxford was just off the town square that William Faulkner had made so famous. He hung out at Hal Waldrip’s General Store in Chulahoma, watched A.G. Newson make molasses, went to Othar Turner’s barbecues (featuring fife and drum music) and studied how Riller Thomas made quilts.

“When I got to north Mississippi and went wandering in late afternoon when it was first frost, I knew what I was seeing,” Ford said during the onstage conversation. “People were self-sufficient,without a lot of outside stuff.”

Michael Ford discusses his work with Aimee Hess, managing editor of the Library’s Publications Office. Photo: Shawn Miller.

The first lesson Hall taught him about blacksmithing? When looking at a piece of metal in the shop, “spit on it to see if it’s hot.”

Mississippi is that kind of place — gut-bucket deep with labor, practicality and mother wit. Ford, new to an old place, was struck by its poverty, by the raw relationship of people to nature. He stuck to a few counties that are to the south and east of Memphis, tucked below Tennessee and not far from the Alabama line. Interstates were things that ran someplace else. In these rolling hills and small villages, he struck up friendships and stayed for four years.

“They’re about the land,” he writes about his pictures of the era, “and about the people living their lives as best they can in the circumstances they are in. I was there in a rural America that was at its end.”

In his lecture, four decades later, he counted himself fortunate to have done so.

“I was lucky to get it,” he said, “while it was there.”

Riller Smith ‘s quilts on the line. Lafayette County, Miss., 1972. Photo: Michael Ford