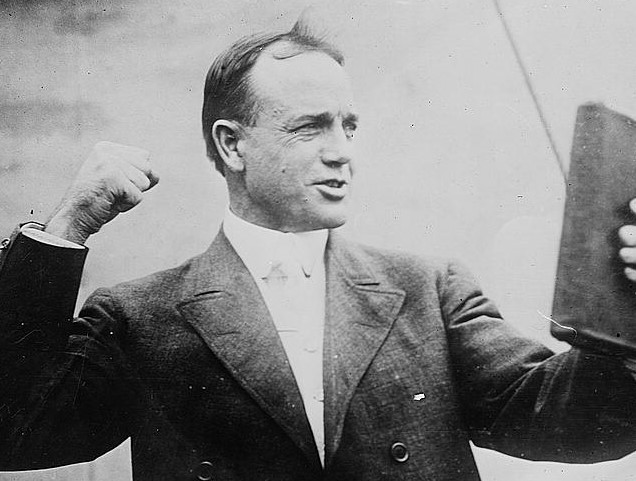

Billy Sunday, in full evangelical form. Prints and Photographs Division.

This is a guest post by Ryan Reft, a historian in the Manuscript Division. His most recent piece for the blog was about the American Federation of Labor.

A. B. MacDonald was a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist in the early decades of the 20th century who had a front-row seat to the sermons of Billy Sunday, one of the most electrifying preachers of the day.

MacDonald, based in Kansas City, was an evangelical Christian himself. He spent much of 1917 to 1919 traveling across the country and proselytizing with Sunday, a man MacDonald repeatedly described as a “genius” and “the greatest man I have ever known.”

His diary from Sunday’s Chicago campaign of 1918 is part of the recently acquired A. B. MacDonald Papers in the Library’s Manuscript Division. The diaries are among the collection’s highlights, notably the two documenting his experiences with the Sunday campaigns. The first was 1917 in New York; the second, Chicago in 1918. The latter provides a window into the reverend’s charisma and religious influence, while also serving as a cartography for much of the city’s industrial and religious life. While Sunday spread the good word to massive crowds, MacDonald evangelized to more modest but still significant gatherings in churches and workplaces across the Windy City.

Crowds jam New York’s Penn Station to see Billy Sunday arrive. Bain News Service, between 1910 -1920. Prints and Photographs Division.

In Chicago, Sunday spoke to thousands on a regular basis. On March 15, 1918, he preached to 5,000 in the afternoon and 12,000 in the evening. According to MacDonald, Sunday could move even the inebriated. Spotting “two drunken men wheeling around in the jam” searching for seats, MacDonald noted, “several times” the two men wiped “tears from their eyes,” as Sunday proselytized.

At other times, MacDonald suggested that Sunday spoke directly to God.

Billy Sunday. Bain News Service, 1915. Prints and Photographs Division.

Once, when it began to rain just before an outdoor speaking engagement, Sunday despaired that it would be impossible for people to hear him over the din of “a mighty downpour.” Sunday then “put his hands to his face, his thumbs upon his cheeks, the open palms of his hands on each side of his mouth, forming a megaphone,” and implored God, “to please let it stop.”

“Strange as it may seem, to some,” MacDonald wrote, “the rain stopped almost instantly and did not begin again until he was through speaking.” Whether or not the rain ended due to Sunday’s lament or, more likely, as a result of meteorological circumstances, MacDonald’s account captures the charismatic attraction of the nation’s leading evangelist.

Burgeoning socialist and labor movements animated the political ferment of the era. Both drew hostility from business leaders, who, in some cases, turned to men of the pulpit to dampen the organizational fervor of workers. Several years earlier, Sunday had taken his message to Philadelphia and other Pennsylvania towns. He had encouraged workers to be “more faithful to their duties.” Labor historian David Montgomery points out that these efforts were “short lived and left no ideological legacy,” but MacDonald and Sunday believed the hearts of workers remained open to Sunday’s interpretation of Christianity.

In this way, for urban and labor historians, MacDonald’s diaries paint a compelling portrait of industrial Chicago. MacDonald spoke to thousands of men and women in their workplaces, including Montgomery Ward, “the big mail order house;” the Kimball Piano Factory; the shops of the Northwestern Railways; the Chicago Screw Company and the Hansell-Elcock Iron Works.

At the Adams Express Company, MacDonald spoke to an audience of 150, mostly men and boys. “The air was blue with tobacco smoke,” he wrote. “They were a rough looking lot of men, but under their coats their hearts were just like mine, and I felt that I spoke to them.” In another, MacDonald proselytized to a room of 400 men standing or sitting on “turning lathes and other machines.”

Sometimes, audiences received his sermons ambivalently. At the aforementioned iron works, a frustrated MacDonald failed to win over his listeners. He wrote, without offering any evidence, that there was not a “Christian” among them. Nor was the journalist above sectarianism. Once, he spoke at a piano and organ factory to a room filled with “girls from 16 to 20 years of age.” Perhaps 90% were Roman Catholics, he wrote, whom the superintendent of the factory said, “didn’t work hard on the job.” MacDonald, despite his journalistic credentials, never questioned the assertion.

MacDonald also traversed the city’s Protestant churches. At the Austin Baptist Church, “the audience was deeply affected. A great many of them were in tears as I concluded.” The audience at the Presbyterian Church in Norwood Park proved more elusive. “The singing was good and I spoke at my best,” he confided in his diary. “As the Methodists say I ‘Had much liberty’ in my address and the audience laughed and cried by turns. But at the end there was not one convert.”

MacDonald’s papers offer numerous other insights from his long career, including his Pulitzer in 1931 of a murderous Texas love triangle; pioneering work on the famous Leo Frank murder trial and subsequent lynching in Georgia; the closing of the Western frontier; the Chautauqua lecture circuit and much more.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.