This is a guest post by Julie Miller, a historian in the Manuscript Division. It offers a window into the social realities of South Carolina in the days leading up to the Civil War, when very different ideas of “freedom” existed side by side. As any reader will notice, such issues persist in different form today.

Henry and Claudia Izard lived at a house called “The Elms” outside Charleston, inherited from Henry’s parents, Ralph and Alice Delancey Izard. After “The Elms” burned in 1807, before his marriage to Claudia, Henry rebuilt it. By 1940, when it was photographed by the Historic American Buildings Survey, the house was in ruins again. Historic American Buildings Survey Photographer C.Ol Greene May. 1940. The Elms (Ruins), University Boulevard (U.S. Route 78), Otranto, Charleston County, SC. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

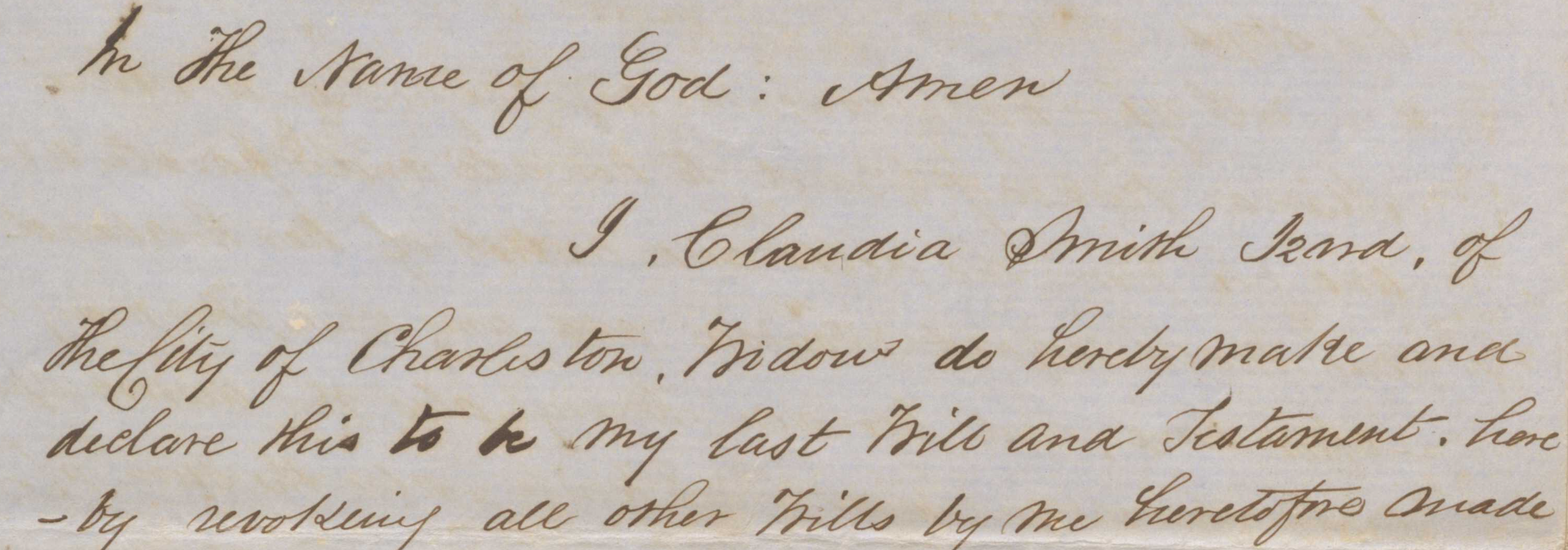

When 84-year-old Charleston widow Claudia Smith Izard made her will in 1853 she showed how two of the most heated issues of her day, slavery and women’s rights, resonated in her life and in the lives of the people around her. Today Izard’s will is at the Library of Congress, along with other papers of the Izard family.

As a young woman Claudia Smith earned a place in Charleston’s mythology when, judged “the wittiest woman in Charleston,” she was chosen to sit next to George Washington at a banquet when he visited the city as president in 1791. Despite her popularity, Claudia, who possessed a substantial income and a house of her own, remained single until 1814 when she was 46. Then she married planter Henry Izard, a widower younger than herself with five children. Henry’s parents, who are the subject of a portrait by John Singleton Copley, were Ralph Izard, an American diplomat in Europe during the Revolutionary War, later a South Carolina congressman and senator, and Alice Delancey Izard.

Ralph and Alice Izard, painted by John Singleton Copley, 1775. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

On his engagement, Henry Izard wrote his mother from Claudia’s house in Charleston: “I last evening brought my little adventure to a close, & am now writing in a room of which I am by courtesy of law, the master.” On receiving this Alice Izard wrote her daughter, dwelling on what Claudia had given up: “She was independent, was beloved by many friends, & saw them often. Now she has a master & a husband not of the gentlest nature.” He was also entangled in debt, and his mother hoped the money and property Claudia brought to the marriage would “help to put him at ease in his affairs.” But Claudia’s money was not enough to save him. In 1826 Henry, who had also suffered the deaths of several of his children, committed suicide.

Twenty-seven years after this catastrophe Claudia Izard wrote her will. With no surviving children of her own, she left her money and property to her nieces, grandnieces and a female friend. Only five men are named in the will, and three of these were her executors. Two men received cash not for themselves, but in trust for their daughters. To those women to whom she left substantial property, Claudia specified that it was for their “sole and separate use and free from the control and debts of her husband.” For those who were unmarried, the phrase “any husband she may have” was substituted for “husband.”

The beginning of Claudia Izard’s will.

These legal phrases hedged against the reality that husbands were legally entitled to own or control their wives’ property after marriage. This is what Henry Izard meant when he declared himself “by courtesy of law, the master” of Claudia’s house. By the middle of the 19th century states were beginning to pass married women’s property acts that overturned the hegemony of husbands, but when Claudia Izard wrote her will South Carolina had yet to do so.

When Claudia, who had regained control of her property at her husband’s death, chose to leave it to the women of her family and protect it from their husbands, she was using a legal remedy that allowed married women to retain control of their property. She may also have been expressing what she felt about being subject to Henry Izard as her master. Her own subjection, however, did not prevent her from subjecting others. Nine slaves are named in her will. The story of one of them, Louisa, her enslaved “maid servant,” is revealing.

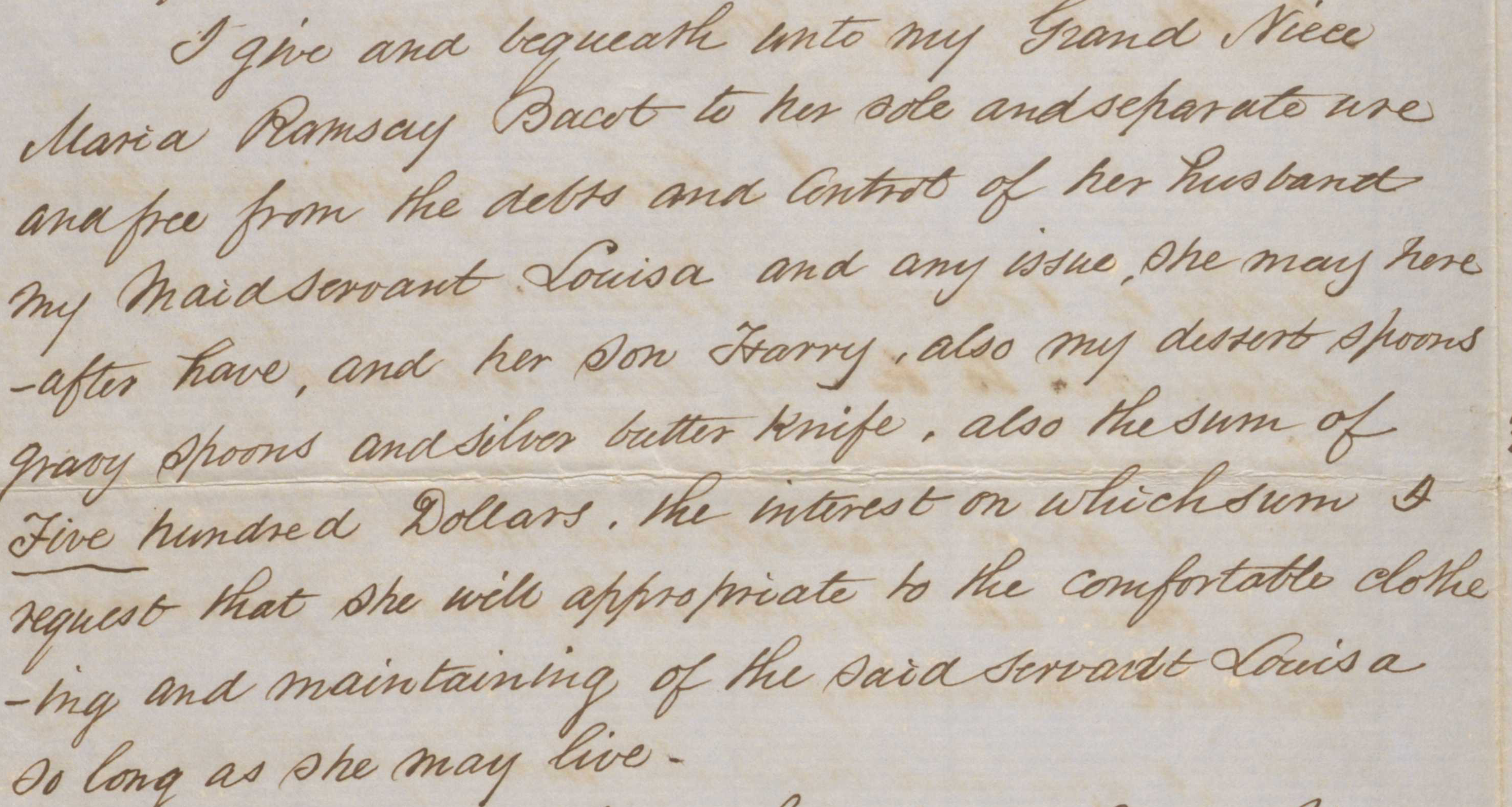

Claudia left Louisa to a grandniece, along with $500, “the interest on which sum I request that she will appropriate to the comfortable clothing and maintaining” of Louisa for the rest of her life. To another grandniece Claudia gave three of Louisa’s children: Benjamin, William and Harry (and added to the gift in the same sentence: “my dessert spoons gravy spoons and silver butter knife”). She made special provisions for William, requesting that he be allowed to “live with and attend upon his grandmother so long as she may desire him to do so.”

Excerpt from Claudia Izard’s will, giving away Louisa’s son Harry along with “dessert spoons.”

Claudia’s treatment of Louisa and her family complicates the picture of her as an upholder of women’s rights. It also makes no moral sense. How was she able to provide for Louisa’s comfort and consider the feelings of William’s grandmother while at the same time wrenching their family apart?

Claudia’s ability to compartmentalize freedom and slavery was the same thing that enabled Thomas Jefferson, another slave owner, to write “all men are created equal” in the Declaration of Independence. She and Jefferson were products of the same culture of slave-holding, but separated by time. By the 1850s the idealism of the revolutionary era, which made it possible even for slaveholders to imagine an end to slavery, had faded in the South. More than three quarters of a century after Jefferson drafted the Declaration of Independence, tensions between North and South over the admission of western territories as free or slave states had made Southerners dig in their heels, arguing that they took better care of their slaves than northern manufacturers did of their workers. Claudia Izard’s will, which robs people of their liberty even as it pretends to provide for their comfort, is a product of the decade before the Civil War when these tensions were blazing.

When Claudia Izard wrote her will she could not know that time would turn it into a historical artifact. She also could not anticipate that with the collapse of the Confederacy in 1865, a decade after her death, her plans for Louisa and her family would also collapse and they would be free.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send one cool story to your inbox Monday-Friday.