This is a guest post by Jer Thorp, the Library’s innovator-in-residence. On November 8, he took over the @LibraryCongress Twitter account to host a #SerendipityRun in which participants connected with one another and shed new light on Library holdings by taking a serendipitous “run” through the online collections. Here Thorp describes the inspiration behind this experiment in making the accidental purposeful.

Let’s start with a story about two men named Horace.

One of them was Horace Walpole, son of the first British prime minister, parliamentarian, art collector, wanderer, man of letters. On January 28, 1754, this Horace wrote a letter to another Horace — Horace Mann, a diplomat living in Florence. In the letter, Walpole described a painting he’d recently acquired by Giorgio Vasari, a portrait of an Italian noblewoman named Bianca Capello.

“Her Serene Highness,” Walpole wrote of the painting, “is arrived safe at a palace lately taken for her in Arlington Street. She has been much visited by the quality and gentry, and pleases universally by the graces of her person and comeliness of her deportment.”

Horace #1 goes on to tell Horace #2 that he has “bespoken” a frame for the painting, an elaborate affair meant to match the elegance of the painting. The frame has the lady’s grand-ducal coronet at top, a label in Latin “as short and expressive as Tacitus” and two coats of arms on the bottom: Capello’s own and the Medici’s (Capello was the second wife of Francesco I de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany). In researching these insignia, Walpole made a discovery, which he shared in his letter to Mann: Both sets of heraldry contained the same symbol, a fleur-de-lis on a blue ball.

This fact came to him not through search but rather through coincidence — through the purchase of the painting and his decision to commission a frame. There is a word for this this kind of discovery, made by chance, and we find it coined for the first time in the next lines of the letter:

This discovery, indeed, is almost of that kind which I call Serendipity, a very expressive word, which, as I have nothing better to tell you, I shall endeavour to explain to you: you will understand it better by the derivation than by the definition. I once read a silly fairy tale, called The Three Princes of Serendip: as their Highnesses travelled, they were always making discoveries, by accidents and sagacity, of things which they were not in quest of: for instance, one of them discovered that a mule blind of the right eye had travelled the same road lately, because the grass was eaten only on the left side, where it was worse than on the right. Now do you understand Serendipity?

Walpole’s phrase — “of things which they were not in quest of” — has rattled around my mind during my year at the Library, one of the world’s great research institutions. As you read this, many dozens of scholars and genealogists, amateur and professional, are filling out call slips, consulting with librarians, viewing materials and making notes in the Library’s many reading rooms. These people, for the most part, are “in quest of” something. They’ve come to the Library to read a particular book, to dig into a specific manuscript, to look at a photograph or to listen to a recording.

But what of those of us who are not in quest of something? What if we come to the Library not to look for a specific thing, but instead in the hopes of stumbling upon something wonderful?

Lately, I’ve been experimenting with ways to foster serendipity, tools and methods that make the accidental a little bit more purposeful. Serendipity is not something that you can try to look at directly. You can do your best to cultivate it, though, and one way to do that is to find fertile soil for chance. For example, Library of Time, a clock that displays time through titles of random objects from the Library’s collection.

A screen shot from the Library of Time.

This is a tool that functions the opposite of a search engine. Indeed, it’s almost impossible to use Library of Time with any specific purpose. Anything that you might find comes from some combination of patience and luck.

Another serendipitous tool I’ve made is called Library of Color. As with the clock, this tool uses the titles of works from the collection. However, it shows them to you in a more ordered way: through the creation of huge color palettes, generated by color words that the titles contain. This tool gives you more control than Library of Time, but it still doesn’t really let you search with purpose. Looking at images whose titles contain the word “blue,” you are as likely to find a musician from New Orleans as you are a postcard of the Aegean. By design, there is a lot of accident to be found.

A screen shot from the Library of Color in which each small color slice represents an object in the collection.

These two tools are fun to use. But they’re a bit lonely, aren’t they? While it’s possible to experience either of them with another person, in a crowd, with a class, chances are you’ll use them alone. One of the things I’ve come to understand about serendipity is that it is a social thing — it works better with friends. People are wonderful engines of chance, and when you engage in the act of finding with another human, or with a group of humans, you are more likely to stumble on the unexpected. Horace #1’s “silly fairy tale” was not, for a reason, titled “The One Prince of Serendip.”

Serendipity also tends to beget more serendipity. In groups, one person’s strange discovery spurs another’s, such that small sparks of coincidence can be readily fanned into bonfires of inspiration. This property of serendipity was at the center of an experiment I led a week ago on the @LibraryCongress Twitter account — #SerendipityRun.

The idea was simple: We’d start with a single item from the collection, and we’d ask the Library’s followers to post things that in some way reminded them of it. We’d Kevin Bacon our way from object to object, from image to book to film to website to web page. Over the course of two hours, we’d see how far and wide we could range as one big, collective, serendipity-powered search engine.

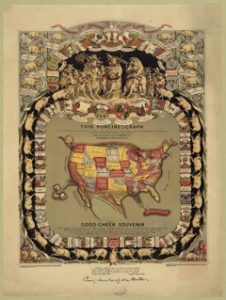

And range, we did. Within the first 10 minutes, we’d moved from a handwritten letter by Rosa Parks to suffragettes on horseback, baobab trees and maps of the Turkish Empire. Later we’d drift together to Babe the Blue Ox, One Direction, W.E.B Du Bois and photos of kittens (of course). We saw aerial images of World War I trenches, hand-drawn diagrams for dances and photographs of Houdini’s great escapes. We ended up at a map of the United States, shaped like a pig.

One of #SerendipityRun’s last surfaced items, a U.S. map in the shape of a pig, surrounded by pigs representing the different states, with notations about state foods.

None of this was planned, which is not to say that our run didn’t take us to useful places. I had no idea that we’d find one of the Library’s banjos or a collection of 2,753 speech accents. One of #SerendipityRun’s participants found a photo of the boat her parents had migrated to the U.S. aboard more than eight decades previously.

Years ago, I had the chance to collaborate with the writer and photographer Teju Cole on a project called “The Time of the Game.” For the piece, Teju engaged with thousands of people on Twitter, asking them to post photos of themselves watching the 2014 World Cup Final. The result was a collection of images, all from different places in the world of the same thing: a soccer game on a television. Working with Mario Klingemann, I made a web interface that overlaid all of these unique images exactly on top of one another so that it looked like everyone was watching the same TV set. In an essay he wrote about the project, Cole referred to “The Time of the Game” as an experiment in “public time,” which he described as the chronological equivalent of public space. “It is basically about finding ways to make the public space intimate, and yet to do it without going directly to Kumbaya,” he wrote. “Under the guise of football, we actually testify to each other’s existence.”

“The Time of the Game” by Teju Cole, Jer Thorp and Mario Klingemann.

#SerendipityRun was likewise an experiment in public time. It gave its participants a chance to be in the Library’s collections together at the same time, to humanize a vast dataset of hundreds of millions of objects together, to weave the stories held by the books and photos and films and banjos with stories of their own, all at the same moment.

Horace #1 said that serendipity was a kind of divination — a seeking of guidance by which by which he found everything he wanted, “à point nommé, wherever I dip for it”. À point nommé: just when needed.

With #SerendipityRun and the projects that will follow over the coming months, I hope that we can all find new ways to roam the Library’s collections, to share public time with others and to discover strange and wonderful things.

Visit labs.loc.gov to see more of the work that Thorp has done as Innovator-in-Residence.