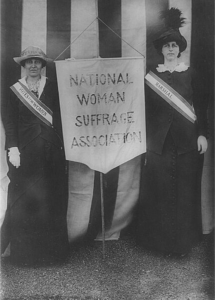

Suffragists Katharine McCormick and Mrs. Charles Parker (first name not recorded). April 1913. Prints and Photographs Division.

This is a guest post by Candice Buchanan, a research librarian in the local history and genealogy section of the Main Reading Room.

Finally. After seven decades spent lecturing, debating, writing, parading, suffering, and all-out fighting for it, women had the right to vote. The 19th Amendment was ratified on August 18, 1920. History was made, although as a practical matter, these gains only applied to white women at the time. Still, the paradigm had shifted.

Did your ancestor take part? Was she for or against such decisive reform?

It can be challenging to discover records that give dimension to the women in our genealogy. Suffrage provides an opportunity.

The enormous suffrage movement produced national superstars whose names are forever connected to the cause. Those women earned their prominence because they rallied broad participation across the country.

The boots-on-the-ground suffragists were the women in your community and family tree. These women labored for reform in their states, counties, cities, churches, schools, social clubs and families. At every level, women had to convince a majority of male voters and legislators to endorse suffrage. Only men could cast the ballots that would grant the same right to women.

Not all women were suffragists. A strong anti-suffrage movement coexisted and counteracted the cause. Some women kept their opinion private. Others avoided the topic altogether. To find out where your relatives were on that spectrum, you can begin with some basic genealogical research.

The suffrage movement lasted from the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848 to the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920. To get started, first identify the women in your family whose lifetimes intersect that era. They did not have to be members of an official pro- or anti-suffrage organization to take a side. Investigate the positions of their social clubs, religious affiliations, political parties, family members, and communities for insights into how they may have viewed suffrage.

Library of Congress Collections and Exhibits

Next, the Library is home to significant historical material related to the suffrage movement, including the special exhibit, “Shall Not Be Denied: Women Fight for the Vote.” The exhibit has a virtual counterpart to explore online, which includes original papers of suffragists and suffrage organizations, photographs, historical accounts and more. Browse digital collections such as the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) Records and utilize resources identified in the 19th Amendment research guide to understand the national movement and provide historical context for the roles your ancestors played.

Suffrage Organization Archives

Each suffrage organization had philosophies and action plans. Knowing which one(s) your ancestors belonged to will help you to understand their perspectives.

The most well-known suffrage organizations were the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) and American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), which merged in 1890 to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). After the 19th Amendment passed in 1920, NAWSA merged with the National Council of Women Voters to form the League of Women Voters, which is still active.

Similarly, the National Federation of Afro-American Women and the National League of Colored Women merged in 1896 to become the National Association of Colored Women (NACW). In 1904, NACW became known as the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (NACWC). Their work to overcome the challenges women of color face in the fight for equal rights is ongoing.

As the movement evolved, these groups continued to merge, adapt, or split. A prominent example of the latter, occurred in1917, when Alice Paul broke away from NAWSA to form the National Woman’s Party.

Other groups, though not specifically created to fight for suffrage, supported the cause. These organizations, such as the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, became important allies.

To find out if your ancestors were members, search for the records of each organization. Seek out state and local chapters from the communities where your ancestors lived. In addition to Library, ArchiveGrid is a useful tool to locate collections at over 1,000 institutions nationwide. Reach out to state or university archives, county historical societies and community libraries. Most archives do not have every-name indexes. You’ll want to find the most likely collections and study their contents for ancestors’ names. If you do not find actual membership rosters, look for alternatives such as meeting minutes, correspondence, newsletters, and programs that may identify ancestors or their neighborhoods.

Newspapers

Suffragist activities were often reported in local newspapers. Sometimes members were identified or quoted. For example, in November 1920, many articles were written about the first women at the polls on Election Day.

The Library provides free access to Chronicling America, a collection of historic newspapers. It’s important to find the newspapers local to your ancestors’ neighborhoods. If those hometown papers are not yet posted to Chronicling America, use the U.S. Newspaper Directory to see which repositories house the archives.

Poll Taxes and Voter Registrations

If her state required a poll tax, find out if she paid it. For some areas, poll taxes have been digitized or published, but in most cases you will need to contact the county tax office or courthouse to access the original records. Voter registrations are also generally maintained at the local level. For family history purposes, these documents may reveal additional facts like name changes, birthdays, occupations, residences and taxable property.

There are limitations to poll tax and voter registration records because, in spite of the 19th Amendment, not everyone was given an equal opportunity to participate. Women of color, like men of color, were forced to overcome intentional obstacles such as literacy tests and the poll tax itself. If your ancestor does not appear as a registered voter, you may want to dig deeper into the local history of their town, county, and state to determine what tactics may have inhibited their opportunity to register to vote.

Poll taxes and voter registrations indicate what your ancestor did with her new right. They do not tell you how she felt about it or whether or not she took an active role in the fight for it. Nevertheless, this historic moment in the lifetimes of our female ancestors should be documented for every woman in the family tree who was qualified to vote on Election Day, November 2, 1920. Whether or not she registered to vote, or tried to register to vote, in the first election for which she was constitutionally eligible, is a relevant part of her story and her place in history

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.