This is a guest post by Ryan Reft, a historian in the Manuscript Division.

“Interpreters were brought from everywhere to instruct our men in the French methods of warfare because be it known that everything American was taken from us except our uniform.”

—Noble Sissle, 369th “Harlem Hell Fighters” Regiment

Recruits for what would become the 369th Regiment, also known as the “Harlem Hell Fighters.”

The Library of Congress exhibition Echoes of the Great War: American Experiences of World War I explores the role of African-American soldiers in the war and ways in which the international conflict contributed to a growing racial consciousness among black veterans.

Over 350,000 African-Americans served overseas for the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) during the war. Most toiled away in important but menial positions—as stevedores, camp laborers, clerks. But between about 40,000 and 50,000 black American troops served under French commanders in the war, largely in the 93rd Division of the AEF, consisting of the 369th through the 372nd regiments. No black troops experienced as much combat as those assigned to the French military.

As historians like Jennifer Keane, Chad Williams and Adriane Lentz-Smith have demonstrated, racism was deeply embedded in the segregated World War I military. Among officers and the rank and file, white soldiers felt no compunction in demeaning their black counterparts. In France, “U.S. troops were busy spreading rumors among the civilian population that blacks were rapists, thieves, and had tails,” Keane points out.

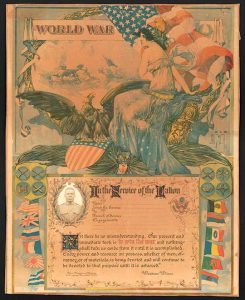

Although the soldier pictured here is unidentified, his uniform indicates that he served with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Its three-towered castle appears on his collar insignia and is echoed in artist Dan Smith’s commemorative certificate.

Although the government organized its first officer’s training camp for black troops during World War I, the camp was segregated. Located in Des Moines, Ia., it trained only enlistees for the infantry. White officers eschewed imparting artillery and engineering skills to camp enlistees even though such skills proved crucial at the front, where many soldiers found themselves assigned to artillery and engineering units. And even in its limited focus on infantry, the camp’s military leaders failed to adequately train their charges for the challenges ahead. The division that emerged from the camp experienced combat, but under white officers who took every opportunity to denigrate the division’s efforts while obscuring their own failures of leadership.

What to do with black soldiers generally once they were trained bedeviled leadership. AEF commander General John J. Pershing and others refused to integrate the armed services, and military leaders struggled with how to assign the 93rd Division. By assigning it to the French army, Pershing fulfilled a pledge to supply combat regiments to the French, while also freeing “himself from the dilemma of how to use the African-American fighting regiments of the provisional 93rd,” writes Williams.

Doing so came with a cost, however. “They now became France’s problem, an act that cast African-American troops as outside the U.S. Army, and in a symbolic sense, outside the nation itself,” Williams states. W.E.B DuBois summed up the treatment endured by black soldiers from their white American counterparts: “[T]he American Negro soldier in France was treated with the same contempt and undemocratic spirit as the American Negro citizen is treated in the U.S.”

The 369th was the first black regiment to reach European shores in late December 1917; it was also the first to gain notoriety for its fighting skills when Henry Johnson and Needham Roberts successfully defeated a German assault, earning the French military’s highest honor, the Croix de Guerre. “The first heroes of the American Army came from that regiment,” wrote Noble Sissle.

He described relations between the French and their African-American counterparts as generally good. French officers befriended African-American troops and officers, while the noncommissioned officers “treated our boys with all the courtesy and comradeship that could be expected.”

Most African-American soldiers, whether fighting for the AEF or the French military, experienced a great deal more freedom in France than they did in the U.S. Though the French had their own racial issues, black Americans found the country devoid of Jim Crow segregation. Many dated French women, which infuriated their white AEF counterparts.

When the 369th returned from the front in 1919, it enjoyed a boisterous parade in New York City to celebrate its contributions. But many other black veterans experienced hostility, finding themselves subject to verbal abuse, assault and even lynching.

“The disillusion of wartime encounters would feed the transformation of black soldiers’ political consciousness,” notes Lentz-Smith of African-Americans in the AEF.

Even before the war concluded, thousands joined civil rights organizations to push for racial equality—from 1917 to 1919, the NAACP expanded its ranks sixfold. More militant veterans allied with the League for Democracy, organized by and for black veterans as a means to promote racial equality and democracy. The government took a dim view of the organization, including it in a 1919 report entitled “Negro Subversion.”

In the end, DuBois captured the attitude of black World War I veterans best in his 1919 poem, “Returning Soldiers”:

We return

We return from fighting

We return fighting

World War I Centennial, 2017–18. With the most comprehensive collection of multiformat World War I holdings in the nation, the Library is a unique resource for primary source materials, education plans, public programs and on-site visitor experiences about the Great War including exhibits, symposia and book talks.