This is a guest post by Kristi Finefield, a reference librarian in the Prints and Photographs Division. An earlier version was published on “Picture This,” the division’s blog.

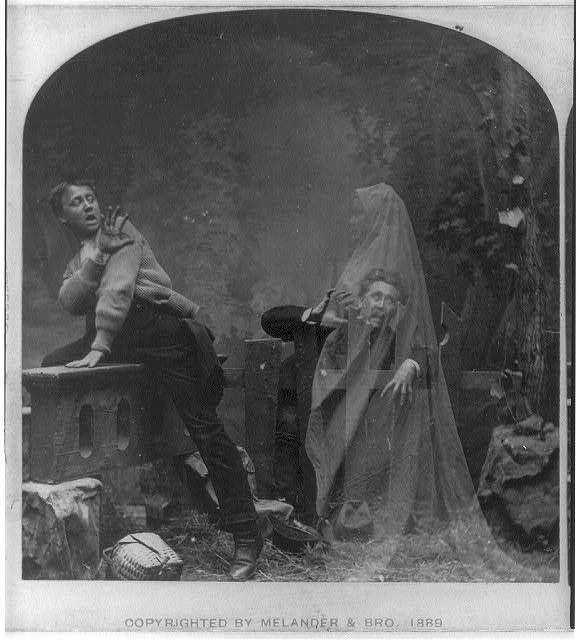

“The Haunted Lane,” a stereograph showing a ghost frightening a boy and a man. Created in 1889 by Melander and Bro.

Can you take a photograph of a ghost? Will a spirit pose for your camera? Looking at “spirit photographs” from the mid-1800s to the early 1900s, you might be tempted to answer, “Yes”!

Claims of capturing a spirit with the camera lens were made as early as the 1850s, when photography was relatively new to the world. At that time, the process of photography was mysterious enough to most people that the idea of a photograph capturing the latent image of a spirit seemed quite possible.

By the time spirit photographs were being publicized in the 1860s, professional photographers had developed several techniques to portray ghost-like apparitions through composite images, double exposures and the like.

In fact, Sir David Brewster, in his 1856 book on the stereoscope, “The Stereoscope: Its History, Theory, and Construction,” gave step-by-step instructions for creating a spirit photo, beginning with:

“Spirit,” a 1901 photograph allegedly documenting a séance. F. W. Fallis, photographer.

For the purpose of amusement, the photographer might carry us even into the regions of the supernatural. His art, as I have elsewhere shewn, enables him to give a spiritual appearance to one or more of his figures, and to exhibit them as “thin air” amid the solid realities of the stereoscopic picture.

He went on to explain how this was easily done. Simply pose your main subjects. Then, when the exposure time is nearly up, have the “spirit” figure enter the scene, holding still for only seconds before moving out of the picture. The “spirit” then appeared as a semi-transparent figure, as seen in “The Haunted Lane.”

One of the more famous—and infamous—spirit photographers was William H. Mumler of Boston. He turned his ability to make photographs with visible spirits into a lucrative business venture, starting in the 1860s. Doubts grew about his work, but even when a spiritualist named Doctor Gardner recognized some of the so-called spirits as living Bostonians, people continued to pay as much as $10 a sitting. Mumler was charged with fraud in 1869, though not convicted, due to lack of evidence. However, his career as a photographer of the spirit world was essentially over.

Celebrities took sides in the debate in the 1920s. Famed author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was an outspoken spiritualist who believed that the supernatural could appear in photographs, while illusionist Harry Houdini denounced mediums as fakes and spirit photography as a hoax. Doyle and Houdini publicly feuded in the newspapers.

Harry Houdini with a ghostly image of Abraham Lincoln.

To demonstrate how easy it was to fake a photograph, Houdini had an image made in the 1920s, showing himself talking with Abraham Lincoln. He even based entire shows around debunking the claims of mediums and the entire idea of spiritualism.

That said, since Halloween will soon be upon us, a day for the spooky and the unexplained, you might want to keep your digital camera handy, just in case!

Learn More

- Try a search in the Prints and Photographs Online Catalog for spirit photographs or Halloween.

- Find out more about Halloween in the collections of the Library of Congress on our updated Halloween page!