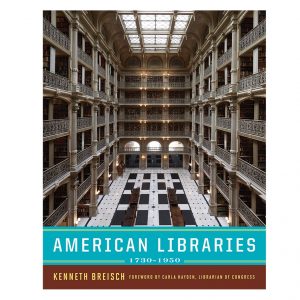

The following is a guest post by Helena Zinkham, chief of the Prints and Photographs Division, about “American Libraries 1730–1950,” published this fall by W.W. Norton and Company in association with the Library of Congress.

You can find libraries at the heart of many different communities, from the center of a town or a college campus to a shared toolbox at a construction site. The new book “American Libraries,” written by architectural historian Kenneth Breisch, takes you on a tour of the interior spaces as well as the public facades of libraries throughout the United States from 1730 to 1950. By way of introduction, here’s a sampler of the more than 450 photographs and architectural designs that fill the volume to the brim.

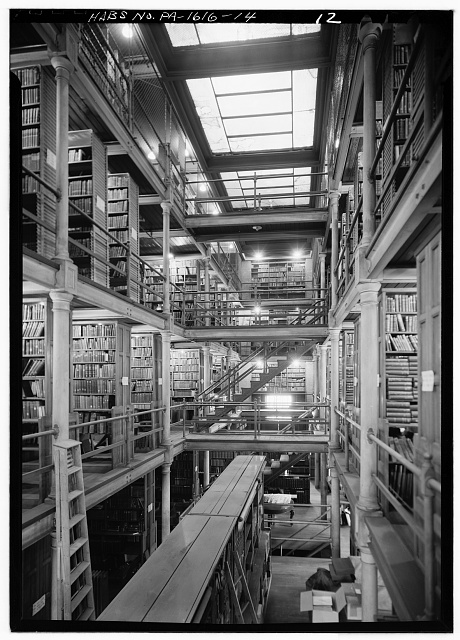

The Library Company of Philadelphia represents the world of private libraries featured in the first chapter. Designed in 1876 by Addison Hutton, multistory iron stacks house the books. I’d love to explore those shelves.

The Library Company of Philadelphia’s stacks. Photograph by Jack Boucher, 1962.

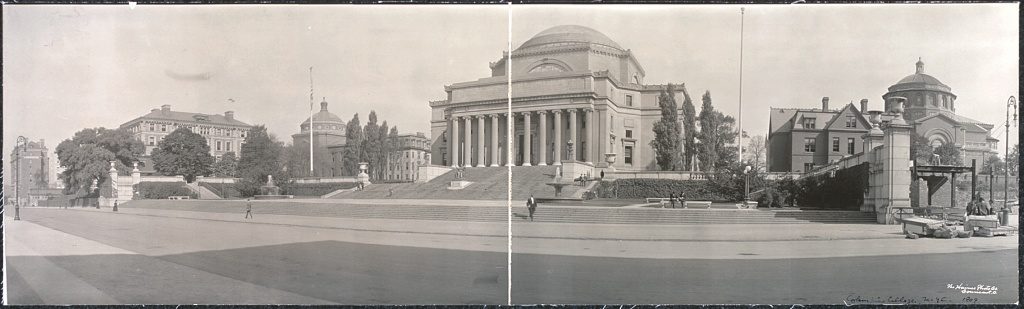

A panoramic view featuring the Low Memorial Library at Columbia University confirms the centrality of a library on a college campus. The academic libraries chapter describes various plans and styles chronologically: early, linear alcove, panoptic, classicism (Low Library), eclecticism and modern.

Low Memorial Library of Columbia University. Photograph by Haines Photo Co., 1909.

The chapter on government libraries features the Library of Congress, from its origins in the United States Capitol to the three buildings that comprise the national library today on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C.

Aerial view of Capitol Hill featuring the three buildings of the Library of Congress—Madison, Jefferson and Adams—in the right foreground. Photograph by Carol M. Highsmith, 2007.

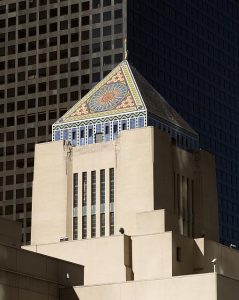

Public libraries are so numerous in the United States that they fill the final three chapters of the book, starting with large urban public libraries from coast to coast.

Enoch Pratt Free Library in Baltimore. Photograph by Carol M. Highsmith, 2011.

Tower of the Central Library in Los Angeles. Photograph by Carol M. Highsmith, 2013.

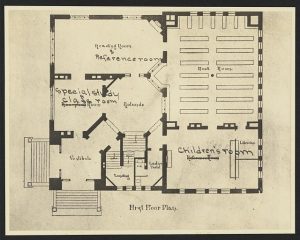

The functional requirements of a public library are clearly delineated in their floor plans: a gracious or inspiring entry area, a space to serve children, a classroom for teaching and study, a reference and reading area and the book stacks. Architect Henry Hobson Richardson introduced the Romanesque Revival style for libraries in the late 1800s, which provided grand, distinctive exteriors as seen in the image below.

First-floor plan for the Scoville Institute, now the Oak Park, Ill., Public Library. Photograph of an architectural drawing by Patton and Fisher, ca. 1886.

Exterior of the Scoville Institute, now the Oak Park, Ill., Public Library. Photograph of an engraving, ca. 1890.

No book on library architecture would be complete without a close look at the Carnegie era of the early 1900s. Andrew Carnegie and his foundation endowed more than 1,600 library buildings in almost every state and territory of the United States. Lighting fixtures might seem to be the focus for the photograph below. But the real joy for a public library is tables crowded with children of many ages, ready to read.

Carnegie Library in Pittsburgh, ca. 1900–05.

From the book’s foreword by the Librarian of Congress, Carla Hayden:

American Libraries 1730-1950” is the 11th and last title in the visual sourcebook series launched by the Library of Congress in collaboration with W. W. Norton in 2003. Bringing this series to conclusion with a book about libraries—their functional designs as well as their beauty and value to society—is especially fitting for us as the national library of the United States.

Learn More

Learn More

- Read the Library of Congress Press Release: New Book Highlights Architecture of U.S. Libraries.

- The Norton/ Library of Congress Visual Sourcebooks series covers barns, canals, theaters, lighthouses, bridges, public markets, Eero Saarinen buildings, dams, cemeteries and railroad stations.