This is a guest post by Yuri Shimoda, a 2018 summer intern with the Junior Fellows Program in the Library’s Recorded Sound Section. She is pursuing her master’s degree in library and information science at the University of California, Los Angeles, with a specialization in media archival studies. Shimoda is the founder and chair of the first student chapter of the Association for Recorded Sound Collections and a recipient of an American Library Association’s 2018–19 Spectrum Scholarship. She plans to become an audio archivist and music librarian.

Yuri Shimoda beside a 1945 master recording of “Cry You Out of My Heart” by Ella Fitzgerald with the Delta Rhythm Boys.

In 2011, Universal Music Group (UMG) donated more than 200,000 master recordings to the Library of Congress’ Recorded Sound Section, which maintains approximately 3.6 million sound recordings at the National Audio-Visual Conservation Center in Culpeper, Virginia. Within the collection’s 5,000 linear feet of material are historic recordings by artists such as Bing Crosby, Louis Armstrong, the Andrews Sisters, Billie Holiday, Guy Lombardo and Les Paul.

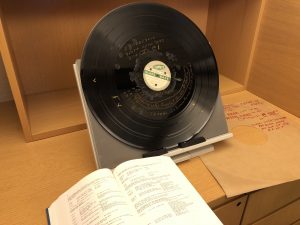

Many of these tracks were recorded onto thousands of 16-inch lacquer discs. Those created during the mid-1940s on UMG’s subsidiary label Decca serve as the focus of my project this summer. My goal for the 10 weeks that I am in Culpeper is to process as many of the discs as possible, which may seem like monotonous work, but has proven to be quite the opposite.

My work days consist of sorting and arranging the discs in order of matrix number, the unique identifier assigned to each recorded track; assigning them a shelf number and barcode; looking up the matrix number in Michel Ruppli’s authoritative discography of Decca recordings; and entering into an inventory spreadsheet information from the discography and from the discs, their original sleeves, or accompanying recording-engineer notes.

Processing lacquer discs entails research to adequately describe each recording.

Some discs might not have a matrix number, artist name or song title written on them, so they become a mystery for me to solve with some online research. In cases where a disc has no identifying information at all, I ask one of the Audio Preservation Unit’s studio engineers to play it so the curator of recorded sound, Matt Barton, and I can find out what songs are on it.

It can be easy to slip into the rhythm of processing without letting the significance of the artist’s name or song’s title I’m entering into the database really sink in. When I actually get to sit down and hear these tracks in the engineer’s studio, though, the impact of how unique and culturally relevant the content of these discs are hits home.

While the aforementioned list of UMG artists is impressive to say the least, and I did feel a thrill of excitement upon coming across an Ella Fitzgerald recording session last week, some of the lesser-known artists like Joe Mooney and a radio-broadcast recording of “The Lonesome Train” cantata, directed by Norman Corwin, about Abraham Lincoln’s funeral train (narrated by Burl Ives) are among what I would call unexpected gems of my exploration thus far.

Once the contents of each disc have been inventoried, I carefully remove the disc from its original envelope to assess its physical condition before placing it into a fresh sleeve. Most of the discs are extremely fragile, since they were made during World War II using a glass base instead of aluminum, due to wartime rationing. Aside from being prone to cracks and breakage, lacquer discs are at risk of other environmental conditions that can speed up deterioration, thus making them a high preservation priority.

Although my experience as the only junior fellow stationed in Culpeper is quite different from my colleagues – while they make their way to work through throngs of tourists visiting our nation’s capital, I might encounter a deer or maybe some rabbits during my daily commute – I would not trade my post for anything. Since I am studying to become an audio archivist, the skills that I am honing and the staff expertise I am exposed to are incredibly valuable. I am enjoying my work with the UMG recordings immensely, and I will be quite sad to leave the discs at the end of the summer.

For more information about the Junior Fellows Program, visit the Library’s website.