This is a guest post by Marianna Stell, a reference assistant, Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

When most of us think of Janis Joplin’s hit song “Piece of My Heart,” it’s her raspy voice that worms its way into our brains, and we start humming, “come, on, come on, take another little piece of my heart now, baby!”

Though Joplin’s version topped the charts in 1968, the song was recorded two years prior by Erma Franklin, Aretha Franklin’s older sister. Both versions express the protagonist’s experience of feeling torn apart. She is appreciated, the song goes, but not enough. Internal fragmentation results.

If medieval manuscripts in the United States had a voice beginning in the early part of the 20th century, they might have sung a similar tune. In the hands of the famous bookdealer Otto Ege, (1888-1951), they were appreciated, but not enough to be supported as whole entities. Ege was a book breaker. He called himself a “Biblioclast.”

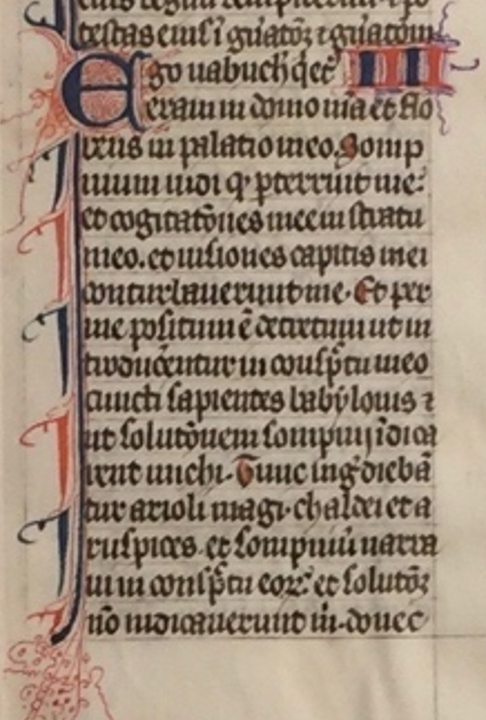

Detail of fragment from a 1310 Bible from one of Ege’s portfolio boxes. Rare Books and Special Collections.

“For more than 25 years,” Ege explained in the March 1938 issue of the hobby journal Avocations, “I have been one of those ‘strange, eccentric, book-tearers.’” An art professor in Cleveland, Ohio, Ege purchased manuscripts, cut them up, and turned them into portfolio books, which he sold to libraries across North America. A detail from one of these, from a 1310 manuscript “Paris Bible,” is pictured at left. It’s written n Latin vulgate in a gothic script. Ege included it in a portfoloio box, “Fifty Original Leaves from Famous Bibles. ”

Ege justified his actions as being democratically motivated. He reasoned that few university libraries and collectors could afford a complete medieval manuscript. By his logic, in breaking these treasures and providing buyers with a sample of manuscript leaves from various times and places, he allowed more people to enjoy access to these fragments of history.

Ege’s argument was sincere if problematic.

Then, as now, a clear financial benefit existed to breaking a manuscript. A bookdealer makes a lot more money by selling individual leaves to different buyers than by selling an entire manuscript to a single buyer. This problem remains well-known to circumspect curators and ethical antiquarian bookdealers, who rely on well-documented provenance records in order to prove that the purchase of an item does not support the dismembering of cultural artifacts.

While no one can turn back the clock and spare these manuscripts from Ege’s destructive appreciation, a new field of digital humanities has emerged as an answer. The Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library is collaborating with the international initiative Fragmentarium.ms to help pioneer what’s called digital fragmentology.

Fragmentarium is building an international community around the ability to identify, search, compare, and collect data on medieval manuscript fragments. What does that mean? For one, it means that libraries across the world can work together to create complete virtual reconstructions of Ege’s manuscripts. One of the most famous reconstructions is the Beauvais Missal for which leaves from more than 60 locations were brought together.

Here in Rare Books, we’re in the process of bolstering our fragment identifications and descriptions so that our fragments—loose leaf fragments, those added to manuscripts or books, and those used as waste in the bindings of other books—can be discovered.

While important information is lost when a manuscript is broken apart, fragments in-and-of themselves can be quite important. During the medieval and early modern period, manuscripts deemed no longer useful were often used as structural support within book bindings. Now, some of these in situ fragments are of greater historical interest than the text block the binding was once fashioned to protect.

Fragment of Ivo of Chartre’s “Dectrtum” pasted to the back board of Leonardus de Utino’s Quadragesimale aurem Venice, Francisus Renner, 1741.

We were recently reminded of this fact when, upon opening a rather homely looking Venetian imprint we discovered a late 11th-century manuscript fragment pasted on the inside of the back board (above). Written in a late Caroline scribal hand that is not especially refined, the text of this fragment is clear enough to be identified as the work of Ivo of Chartres.

Ivo was bishop of Chartres Cathedral in Paris from 1090 until his death in 1115. His writings were foundational to the development of the late medieval legal tradition, and his influence was immediate and widespread throughout Europe.

The Library’s fragment corresponds to the section of Ivo’s Decretum—a collection of decisions and judgments in canon law—in which the bishop discusses baptism. Based on the scribal hand, the Library’s fragment likely dates to the end of the 11th century, right around the time the Decretum was being created, and toward the end of Ivo’s life.

This fragment was likely later used as binding waste because it had no aesthetic value and the text was for some reason not considered useful.

Piecing together the narratives of these fragments helps scholars reconstruct portions of history that would otherwise remain locked in vaults or portfolios. In making the fragment collection more accessible, we hope to encourage a healthy appreciation of fragments that leads to constructive conversations and discourages destructive collecting habits.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.