As the 75th anniversary of D-Day approaches, Ryan Moore, a cartographic specialist in the Geography and Map Division, writes about a top-secret map used in the invasion.

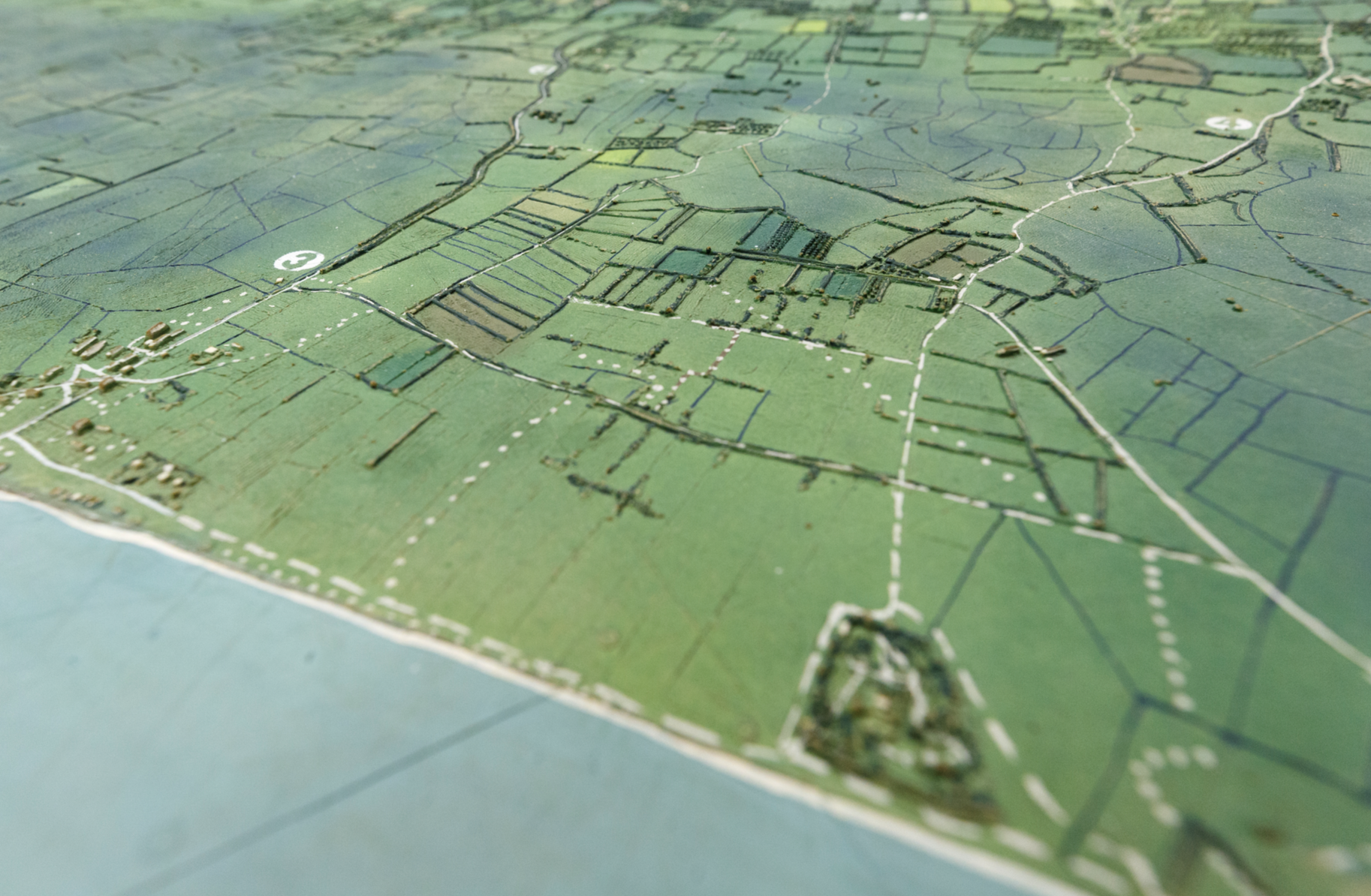

The model of Utah Beach used to brief Eisenhower and Montgomery the night before D-Day. Photo: Shawn Miller.

On June 6, 1944, Allied landing crafts approached the French coast to commence D-Day. The troops aboard knew that murderous machine gun and artillery fire awaited them.

But the liberation of Europe would take more than overcoming the German military immediately before them. It required overcoming the terrain, too: the beaches, the heights above them, the marshes just inland and the open fields cut into rectangular sections by tall hedgerows. It was the power of American mapping intelligence that helped the men in this momentous battle that became known as the “The Day of Days.”

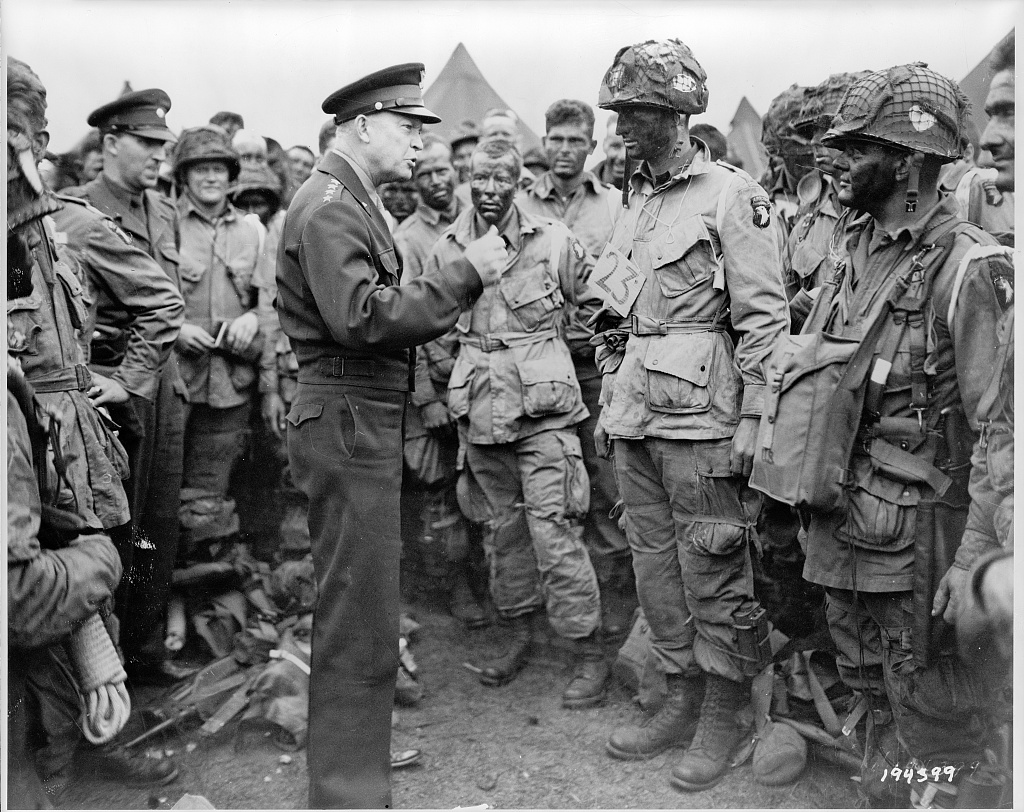

The night before the invasion — dubbed Operation Overlord — Allied Supreme Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower, British General Bernard Montgomery and other leaders gathered in Portsmouth, a port city on the English Channel, for a last briefing on everything from the weather to the terrain. One of the key presenters was U.S. Navy Lt. Commander Charles Lee Burwell, a 27-year-old Harvard graduate who, while being “scared to death,” nonetheless delivered a short talk on the tides and the thousands of star-shaped steel barbs called “Czech hedgehogs” that the Germans had dropped just offshore to wreck landing crafts.

Charles L. Burwell, interview with the Library in 2003.

The map Burwell and others were using for this top-level briefing was spectacular: a one-of-kind, three-dimensional model of Utah Beach, the code name for beaches near Pouppeville, La Madeleine, and Manche, France. The top-secret model, made of rubber on two 4×4 sections, depicted the beach and the interior pastures sectioned off by those hedgerows, a geographic feature that obstructed lines of sight and created conditions for deadly, close-quarter combat. Later that night, Burwell took the model aboard transport ships, showing the commanders and troops the same raised maps of the terrain they would see for the first time in a few hours.

“(The soldiers) identified with it, ‘That’s really a road I’m going to come next to a little forest, and woodland, a here’s a field,’ ” Burwell later told the Library in an interview. “I think it made a lot of difference. It was a technology worth developing.”

Utah Beach model, detail. U.S. Navy, 1944. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Burwell hung onto the model after the war and donated it to the Library’s Geography and Map Division in 2003. You can see it by appointment.

But in mid 1944, the model, along with all other details of the invasion of Nazi-occupied France, was a closely guarded secret. It could only be unveiled once Eisenhower ordered the invasion to begin. Information on the map had come from life-threatening missions over enemy territory. Allied pilots had sortied over the Normandy beaches, under German fire, to make up-to-date, stereo aerial photographs, which provide the illusion of three dimensions to the viewer. American and British reconnaissance teams, who risked life and limb, had gathered information on sandbars and other features otherwise unobservable from photographs and maps.

This data was sent across the Atlantic to the Navy’s Special Devices Division in Camp Bradford, Virginia, which assembled the model. Just prior to the invasion, American pilots flew it back to Portsmouth, the staging ground for the invasion. There, Burwell and others used them in their briefings to Eisenhower and Montgomery.

“I would have preferred to go on one of those beaches,” Burwell said of his nerves that night, in the Library interview. He recalled the auditorium, that the models were elevated so that they could be clearly seen – and that Montgomery, the legendary British commander, was a dapper dresser. “He didn’t look like he was going to battle; he looked like he was going to Greenwich village night club.”

Eisenhower giving final instructions to paratroopers before D-Day. U.S. Army photo. Prints and Photographs Division.

The crux of the D-Day plan was that Allied troops were to land between the Cotentin Peninsula and Le Havre and gain a secure foothold for reinforcements and supplies. The Americans were to take Utah Beach and Omaha Beach. The British and Canadians were to seize three beaches code named Gold, Sword, and Juno. In order to execute the plan, the tides at Normandy had to be low, thereby exposing the star-shaped Czech hedgehogs, so that demolition teams could knock them out. The moon would have to provide ample light for paratroopers to drop in behind enemy lines the night before. Allied meteorologists predicted that between June 4 and June 6 that those conditions were likely to be met.

But foul weather intervened, delaying the invasion. The troops, having already been briefed and aboard transport ships, had to wait it out in rough seas, as commanders feared that if they returned ashore, they might let the secret slip.

The bad weather passed. The secret held. And on June 6, the invasion began.

Paratroopers dropped in behind enemy lines an hour or so after midnight. Infantry and tanks hit the beaches at dawn. On Utah Beach, the men rapidly overwhelmed the surprised defenders, suffering roughly 170 casualties. The scene at Omaha Beach was dramatically different. Some 24 miles away, the troops there endured withering fire from a determined German defense, leaving some 2,000 men as casualties. Airborne troops suffered the worst, with 2,499 casualties. In all, more than 4,400 Allied troops were killed on D-Day.

Overhead view of the entire map, showing English Channel, beaches, and inland fields. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Still, by mid-afternoon, tens of thousands of troops were coming ashore, along with tanks and transports and machinery. These reinforcements were needed to secure the beaches and to push inland.

“Just chaos,” Burwell said, recalling the number of broken-down jeeps in the sand on Utah Beach and the waves of troops and tanks still going forward. He had come ashore, just for a few minutes. He was standing on the real ground that the model had depicted, and the troops who had used it were now moving inland.

The liberation of Western Europe was underway. There would be many hard-fought battles before Nazi Germany surrendered 11 months later. As Eisenhower said of D-Day, it wasn’t the end, but it was the beginning of the end.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.