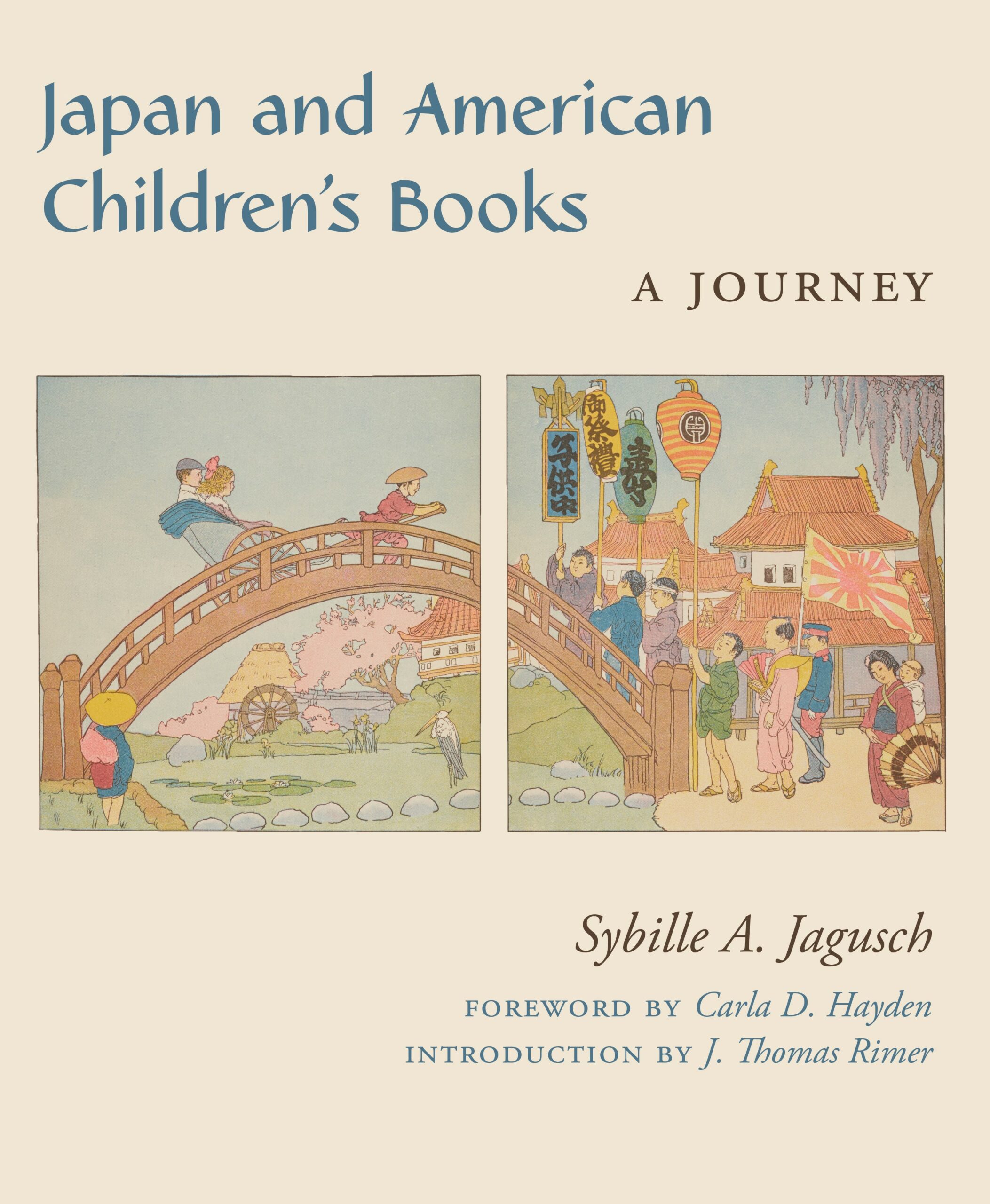

“Japan and American Children’s Books,” by Sybille Jagusch. Published by the Library and Rutgers University Press.

As children, books are one of our first ways of experiencing the wider world. They’re often our first exposure to new and different people, places and cultures. They’re written by adults, though, so in a looking-through-the-other-end-of-the-telescope way, they also tell us a lot about the older generation that writes, illustrates and publishes them.

That’s the brilliant manner in which Sybille Jagusch, chief of the Library’s Children’s Literature Center, views the relationship between Japan and the United States in her new book, “Japan and American Children’s Books.” It’s published by Rutgers University Press in association with the Library.

The gorgeously illustrated, 385-page book is a window into both cultures as they have evolved over the past two centuries, but its focus is on the stories and illustrations that Americans have chosen to show their children about Japan. It’s not always a pretty picture, with stereotypes, caricatures and exoticism dominating the early years, but it has also resulted in beautiful stories, pictures and narratives that will last for generations.

“My intent was not to evaluate how correctly an American writer would portray American and Japanese cultures,” Jagusch said in a recent interview. “It’s to give the reader an overall picture of Japanese culture as it was portrayed by Americans. Those books today are very up to date. That was not the case in the early days, in the 19th century, because children’s books were not as highly regarded as they are today.”

Lady Murasaki Shikibu and Sei Shonagon in “Japanese Portraits,” by Dorothy and Thomas Hoobler, illustrated by Victoria Bruck, p. 13. Raintree SteckVaughn, 1994. Courtesy of Victoria Bruck Vebell.

Jagusch was appointed chief of the Children’s Literature Center in 1983. Over the ensuing years, she’s expanded the Library’s collections of rare and remarkable children’s literature, organized exhibitions and symposia and brought together an international book community. The Library now holds more than 600,000 children’s books, periodicals, maps and other items.

She became fascinated with Japan shortly after taking the helm of the Literature Center. Tayo Shima, a children’s book editor, walked into her office as a volunteer. The pair struck up a friendship and put together exhibitions and books on Japanese and American children’s books.

The papers from their first conference were published as “Window on Japan: Japanese Children’s Books and Television Today.” A companion volume, “Japanese Children’s Books at the Library of Congress: A Bibliography of Books from the Postwar Years, 1946-1985,” was also published.

Jagusch soon began traveling to Japan, touring the country, developing friendships and becoming a collector of Japanese children’s books.

This book, two decades in the making, walks readers through the history of Japan’s appearance in U.S. children’s books. As Jagusch points out, the U.S. published very few children’s books and magazines in the 18th and early 19th centuries, a time when Japan was also almost entirely closed to outsiders.

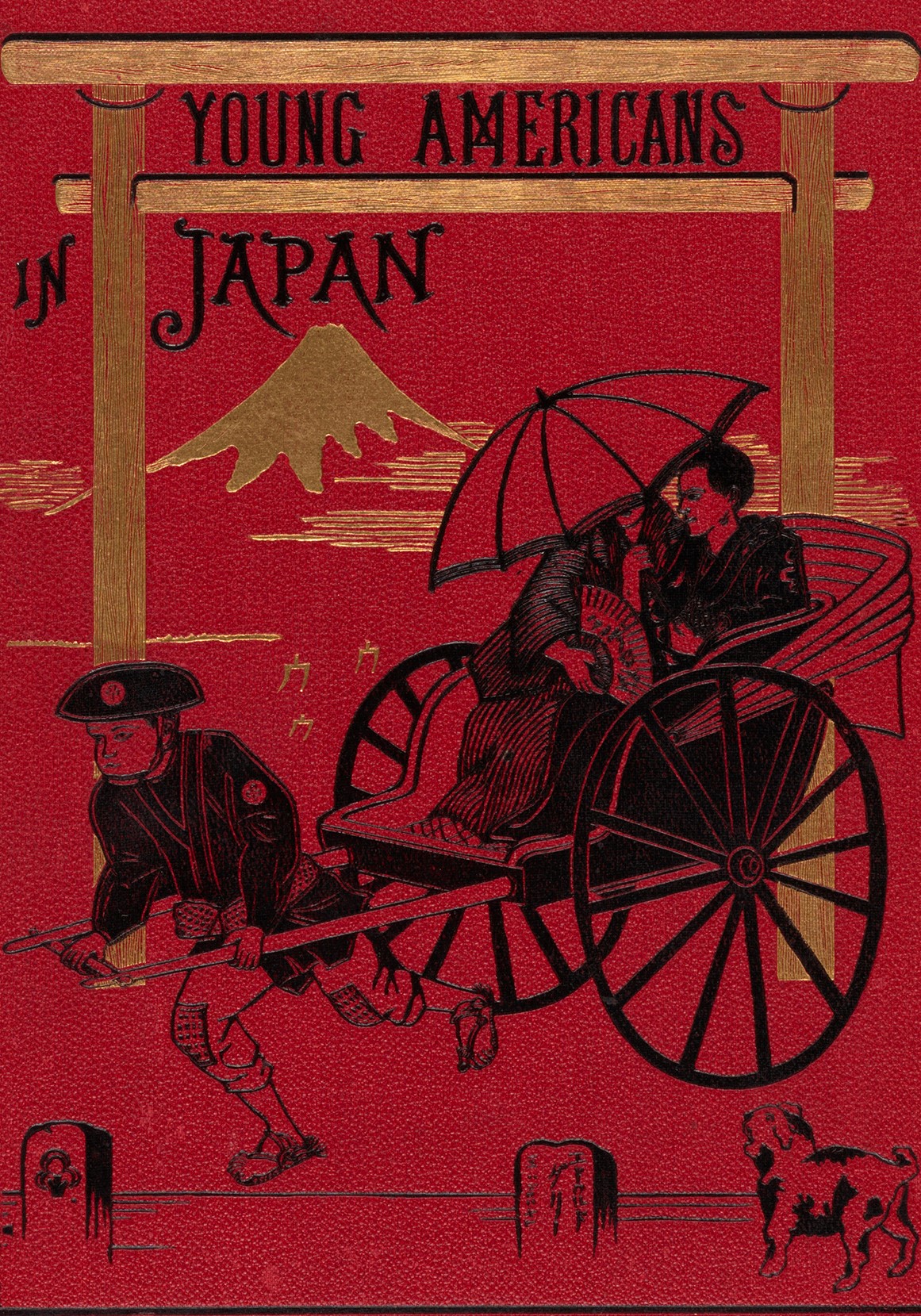

But in 1853, a gunboat trip by U.S. Commodore Matthew Perry to Edo (Tokyo) Bay resulted in a treaty that opened the nation to international trade and culture. Americans immediately saw it as a land of the exotic and told their children the same. Merry’s Museum and Parley’s Magazine, one of the few children’s magazines of the era, made a short mention of the place several years after Perry’s visit: “So wholly unknown, so strange, so curious, Japan seems like a new world, and her inhabitants like a new race of beings. It will be a long time before we shall become fully acquainted with them.”

“Young Americans in Japan; or, The Adventures of the Jewett Family and Their Friend Oto Nambo,” by Edward Greey. Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1882.

This approach would continue for decades, Jagusch writes. Algernon Mitford, a British diplomat and linguist, sought to correct some of most egregious errors. His research into traditional folklore, collected into “Tales of Old Japan” in 1871, included what are believed to be the first Japanese fairy tales printed in a Western language.

“These are the first tales which are put into a Japanese child’s hands; and it is with these, and such as these, that the Japanese mother hushes her little ones to sleep,” he wrote. “[t]those which I give here are the only ones which I could find in print; and if I asked the Japanese to tell me others, they only thought I was laughing at them, and changed the subject.”

The collection included magical stories in which people and animals shape-shift. There’s “The Accomplished and Lucky Tea Kettle,” which miraculously transforms itself into a badger; and “The Story of the Old Man Who Made Withered Trees to Blossom,” which begins with the man’s dog finding a pot of gold.

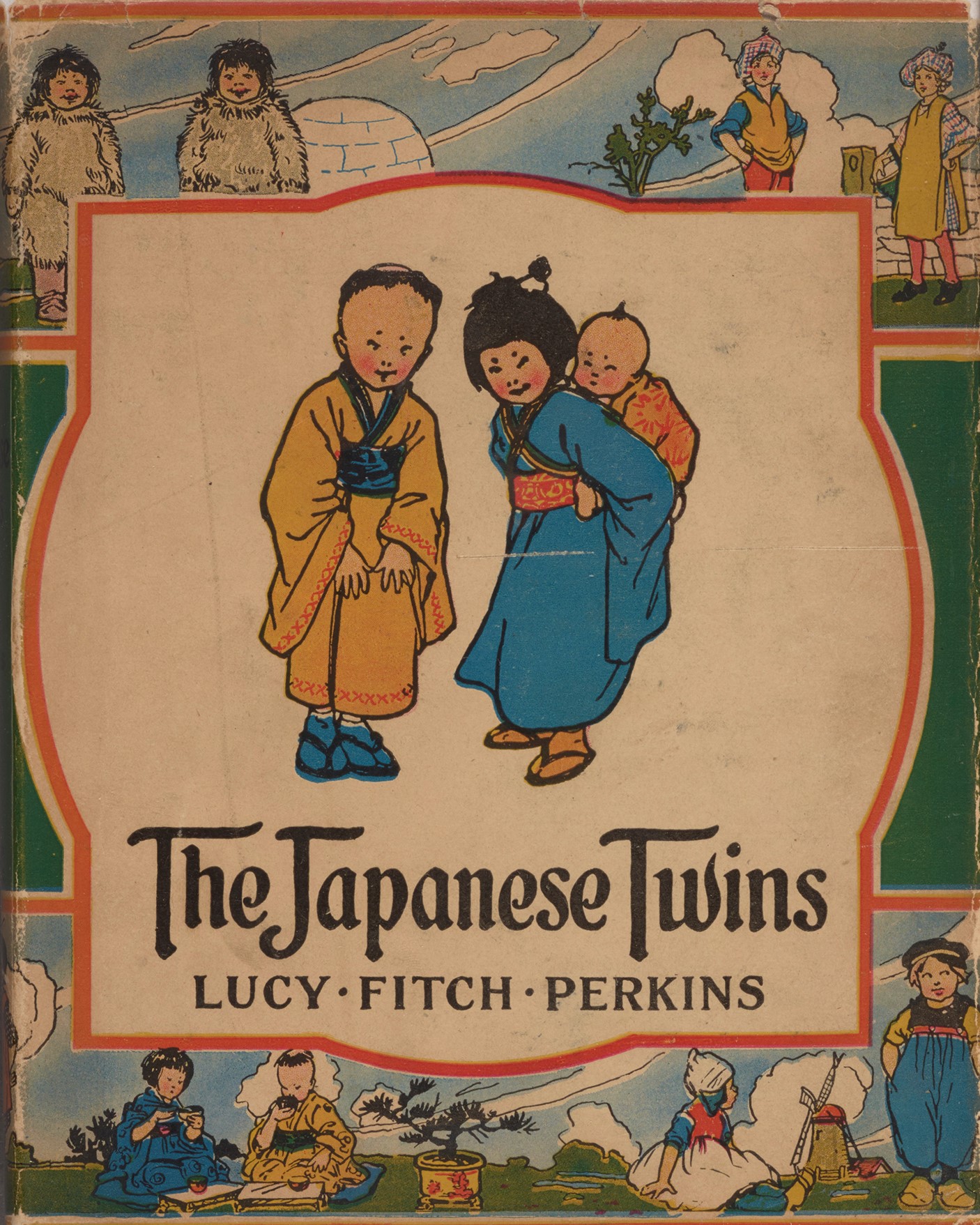

“The Japanese Twins,” written and illustrated by Lucy Fitch Perkins. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1912.

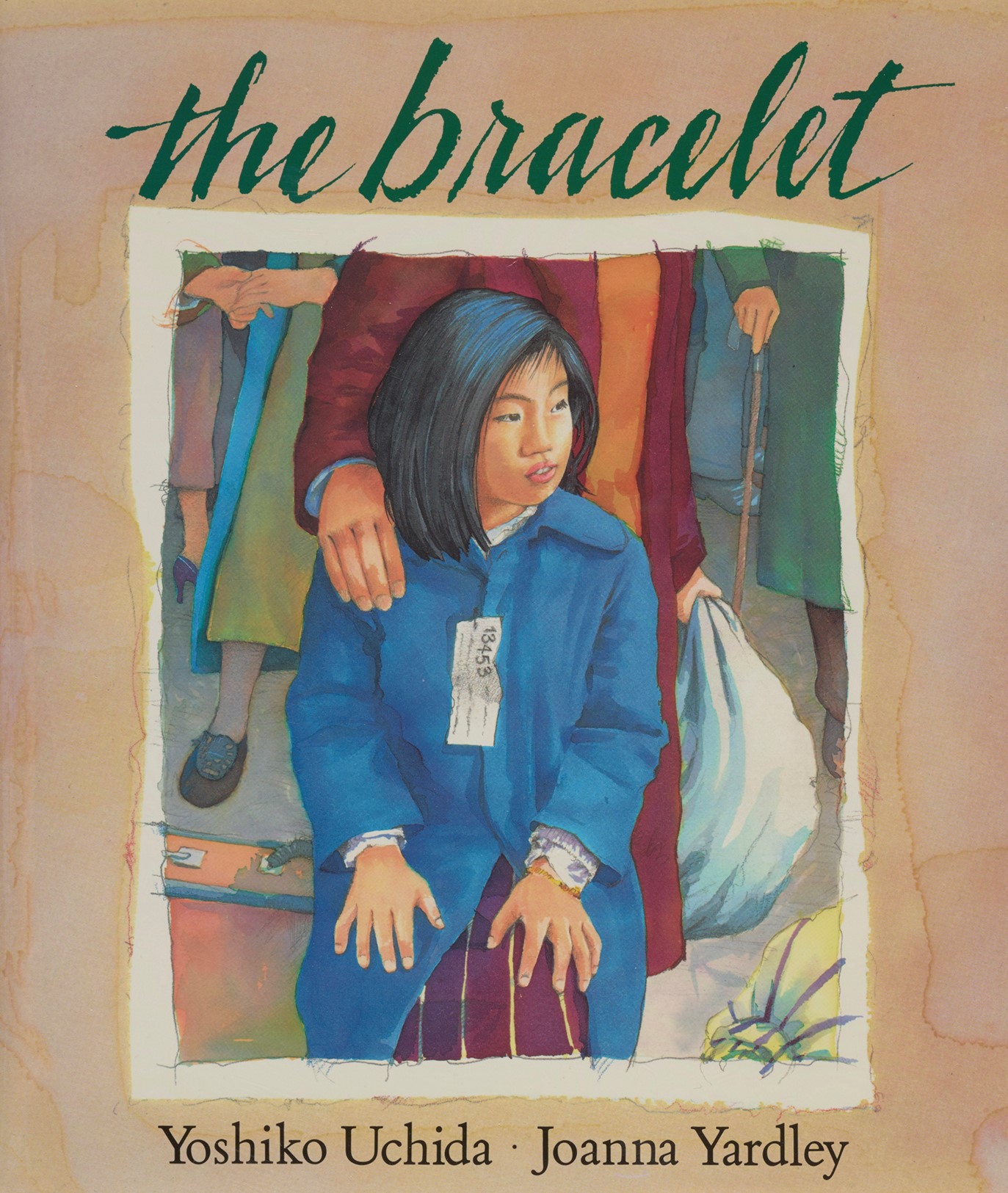

Americans seemed to cling to the idea of Japan as a realm of the mysterious until the eve of World War II. The horrors of war – the brutality of the Pacific Theater, the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the internment of Japanese-Americans – were seldom reflected in children’s books of the mid-century. But, afterwards, a new realism about Japan began to appear in American children’s books, led in no small part by Japanese-American storytellers and artists who help bridge the cultural gaps. Writers such as Taro Yashima and Yoshiko Uchida created authentic and serious works, not fearing to touch subjects like the war years and the immigrant experience.

“The shift away from the exotic towards the familiar and down-to-earth is obvious, and mirrors in turn the level of increased familiarity between the two cultures,” writes J. Thomas Rimer, professor emeritus in the Department of East Asian Languages & Literatures at the University of Pittsburgh, in the book’s introduction.

As a native German, Jagusch said she found an affinity between the two cultures and became comfortable with the idea of herself as a traveler between two worlds.

“These children’s books with their special point of view and purpose reveal the evolving relationship between Japan and America,” she writes in the book’s introductory note. “They also provide a glimpse of a traveler between these two places.”

“The Bracelet,” by Yoshiko Uchida, illustrated by Joanna Yardley. 1993. Courtesy of Joanna Yardley.

“Japan and American Children’s Books” is available in hardcover ($120.00), softcover ($49.95) and e-book ($49.95) formats from booksellers worldwide. Softcovers are available for purchase from the Library of Congress shop.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox