This is a guest blog by Barbara Bair, a historian in the Manuscript Division.

“I wish that I could look out over the desert with you for a moment – Georgia.” From New Mexico, December 1, 1939, Georgia O’Keeffe to Henwar Rodakiewicz. From the Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz Collection, Manuscript Division. Box 1, Folder 13.

The Library’s Manuscript Division has acquired a collection of long-lost letters written by Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz that offer insight into the couple’s art, marriage and ambitions during an eighteen-year span in which they were primary shapers of American Modernism.

The letters — never available to the public until now – were written, independently of one another, to their mutual friend and artistic colleague, the filmmaker Henwar Rodakiewicz, between 1929 and 1947. After being in private hands for decades in Santa Fe, New Mexico, they are now available to the public in the Manuscript Reading Room. (They are not digitized.)

Stieglitz’s letters, written mainly from New York City and Lake George, reveal behind-the-scenes details of his management of his third and last gallery in Manhattan, An American Place, as he showcased O’Keeffe’s art work there along with that of Marsden Hartley, Arthur Dove and John Marin.

But it is the letters from O’Keeffe that compose the bulk of the newly revealed find.

Georgia O’Keeffe. Photograph by Alfred Stieglitz, 1919. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, The Alfred Stieglitz Collection, Gift of Georgia O’Keeffe, [reproduction number, e.g., LC-USZ62-123456].

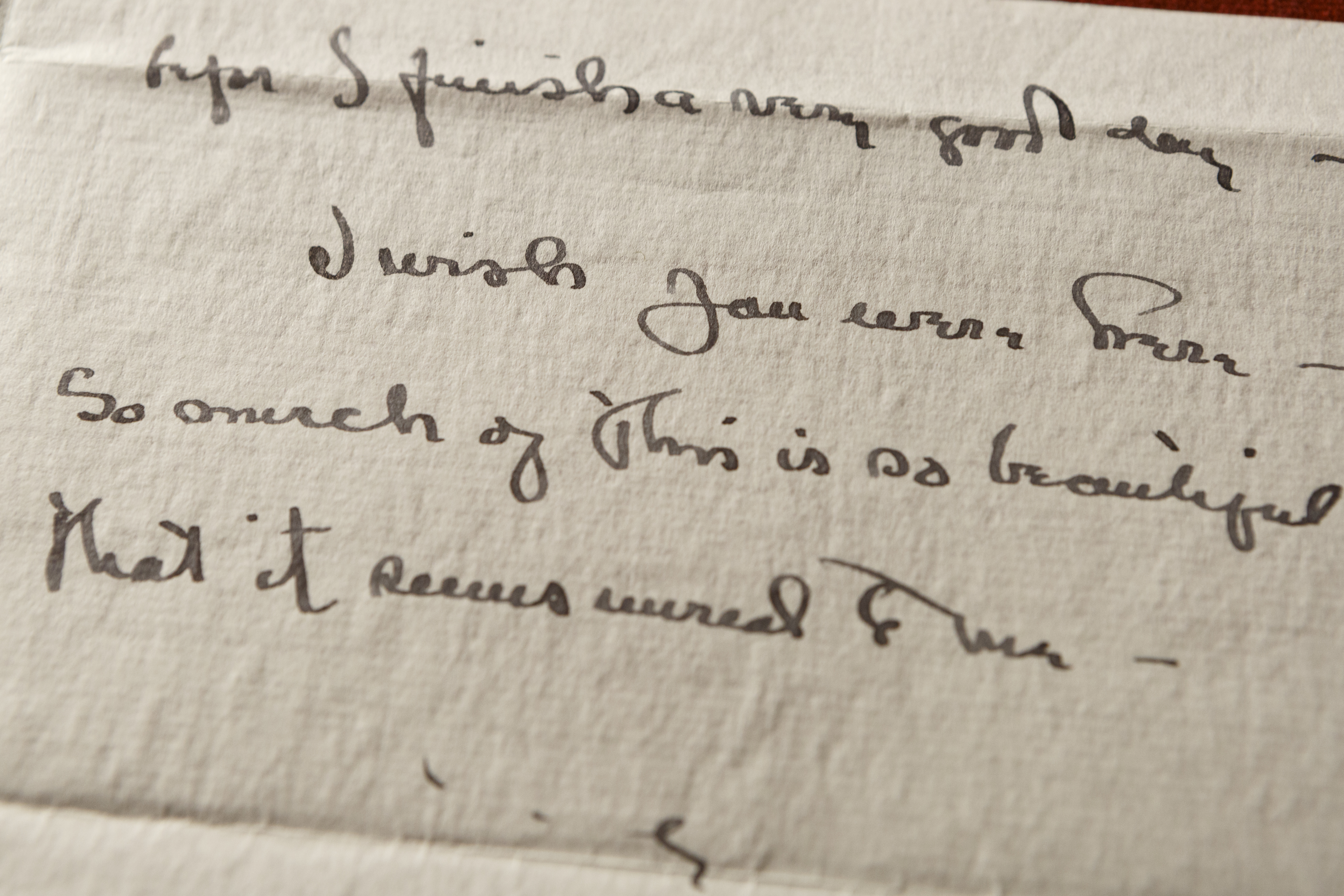

Written from both New York and New Mexico, they are sensitive, sensual and personally revealing. She pens them in her distinctively expressive calligraphy, with dashes and innovative spellings that make the letters read like a cross between Emily Dickinson and Gertrude Stein. She writes of her well-being and artistic hopes, and shares descriptions of the world around her, written through her unique vision as a painter.

Going to the Southwest invigorated her and stirred her to take new directions in her art work. “Here it is color again,” she writes in October, 1938. “I am painting an old horses head that I picked out of some red earth,” she says in another.

“I am painting an old horses head that I picked out of some red earth…” Georgia O’Keeffe to Henwar Rodakiewicz, from New Mexico, Summer 1936. From the Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz Collection, Manuscript Division. Box 1, Folder 8.

“I’ve been a long time resting myself since you went off into the sunset that afternoon — Now that I begin to feel good – really rested – I wish that I could see you,” she writes in December, 1939. “– wish that I could look out over the desert with you for a moment.”

There’s a long, kite-tail line of black ink that sighs down into her sign-off: “Georgia.”

In Sept. 1937, she wrote that she had clambered onto the roof of her adobe house at Ghost Ranch in New Mexico in the darkness: “But tonight the whole cliff is white and full of color in the moonlight. I went up the ladder alone with my coat on – pretty chilly and cheerless on the roof but the whole cliff is white And it seems some thing to tell you.”

“but tonight the whole cliff is white….” Georgia O’Keeffe to Henwar Rodakiewicz, from New Mexico, Sept. 1937. On Ghost Ranch letterhead. From the Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz Collection, Manuscript Division. Box 1, Folder 10.

And on the last day of January 1939, she dashed off a few lines to him on stationery from The Streamliner, the Union Pacific train that ran from Chicago to Los Angeles. “Wyoming with thin sun and blowing snow is beautiful — cold drifting snow, as if there are no people — as we come to pine trees they look black in the whiteness — white in the air and white on the ground.”

O’Keeffe and Rodakiewicz first met in New Mexico in 1929, when she and fellow artist Rebecca Salsbury Strand [James], spent months together in Taos and became part of Mabel Dodge Luhan’s artistic network. O’Keeffe stayed and painted in subsequent years as a guest at the H&M Ranch in Alcalde, New Mexico, owned by Rodakiewicz and his wife, the writer Marie Tudor Garland. From there she explored the area that would become her eventual permanent home, near Abiquiu.

Both O’Keeffe and Rodakiewicz were married during most of the time period of these exchanges. O’Keeffe, famously to Stieglitz until his death in 1946; Rodakiewicz, first to Garland, and later, to Peggy Bok—both of whom were good friends of O’Keeffe’s.

It is not known if their relationship went beyond platonic friendship, but these letters document that O’Keeffe felt emotionally close to him. She writes to him as a trusted confidante, revealing her feelings, her vision, and her work as an artist.

Georgia O’Keeffe. Photograph by Carl Van Vechten, 1950. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Carl Van Vechten Collection, [reproduction number, e.g., LC-USZ62-54231]

At the same time, Stieglitz’s letters also reveal a close bond of affection for Rodakiewicz, and mutual ties in the New York art world.

The new trove of correspondence came to the Library as a purchase/gift from Susan Todd and Michael Kramm of Santa Fe, New Mexico, through the auspices of art and manuscript dealer William Channing.

The materials complement letters in other archives, most notably at Yale’s Beinecke Library. Taken together, these letters add fuller dimension to the complexities of O’Keeffe as person, wife, friend and artist.

In them, she writes notes from trains; on the same paper or stationery that Stieglitz uses from their apartment at the Shelton Hotel in New York; from the Stieglitz family property, The Hill, at Lake George; and on letterhead from Ghost Ranch, which used her design of a cow-skull emblem.

She mentions her travels to Canada, Bermuda and Hawaii, as well as the complexities of her life split between residences in New Mexico and New York. She writes of periods of inner turmoil and longing, of anxieties suffered, and joys in new works and artistic triumphs. She reports conundrums as she makes professional and personal commitments outside Stieglitz’s orbit, in her effort to strike out more on her own, and around the responsibilities that fell to her to settle Stieglitz’s estate after his death in 1946.

“I wish you were here – So much of this is so beautiful that it seems unreal to me.” Georgia O’Keeffe to Henwar Rodakiewicz, writing from Hawaii, ca. Feb.-April 1939. From the Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz Collection, Manuscript Division.Box 1, Folder 13

During their correspondence, Rodakiewicz worked on a series of films. Stieglitz showed Rodakiewicz’s short film, “Portrait of a Young Man in Three Movements” at An American Place in 1933. Rodakiewicz collaborated with Paul Strand on the artistically acclaimed “Redes” in Mexico. Released in that country in 1936, the film was distributed in the United States as “The Wave” in 1937. His “One Tenth of Our Nation,” about discrimination in African American education in the South, briefly landed him in jail for violating local Jim Crow mores.

The letters between O’Keeffe and Rodakiewicz came to an end in 1947, after Rodakiewicz featured O’Keeffe as a southwestern artist in “The Land of Enchantment.”

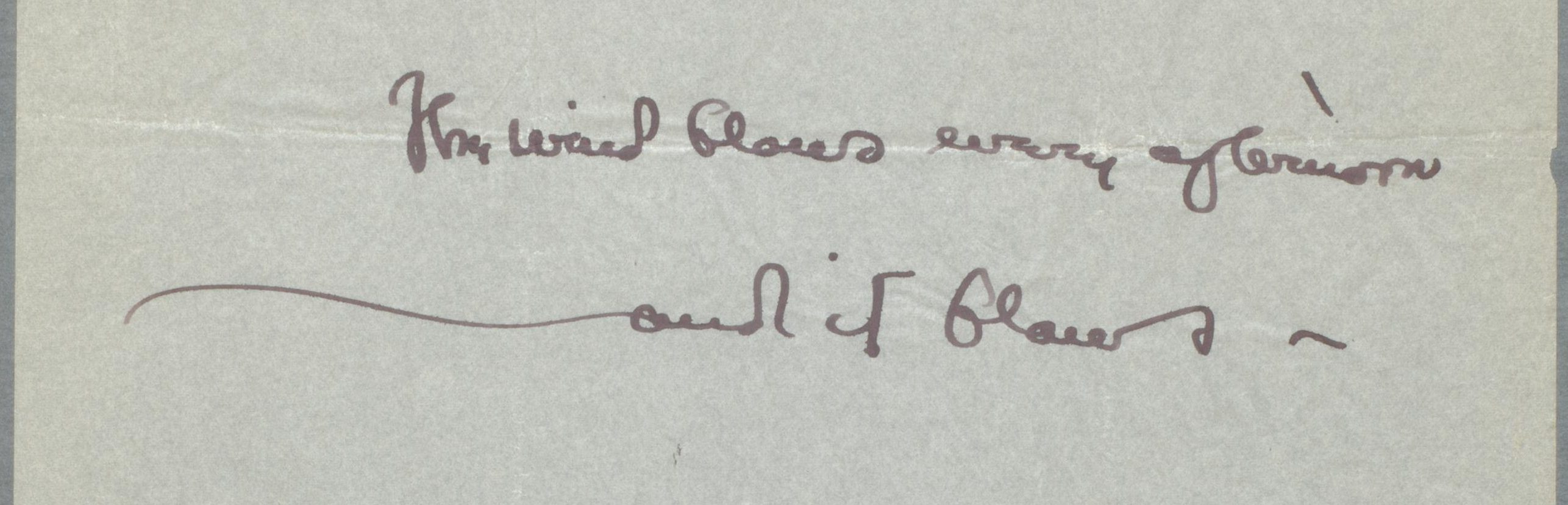

“The wind blows every afternoon,” O’Keeffe wrote to him at the end of one June 1945 missive from New Mexico, with a long line running to form the end of the sentence, “and it blows.”

As calligraphy, as an expression that seems to carry a tantalizing meaning beyond the words on the page, it’s beautiful. It is O’Keeffe in her element and at her philosophical best, and one of many revelatory passages in this new group of letters.

Georgia O’Keeffe to Henwar Rodakiewicz. From the Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz Collection, Manuscript Division.Box 1, Folder 13.