This is a guest post by Barbara Bair, a historian in the Manuscript Division.

Frederick Law Olmsted, 1893. Engraving by T. Johnson from a photograph by James Notman.

Frederick Law Olmsted (1822–1903) is most famous as the creator in the late 1850s of New York City’s Central Park with Calvert Vaux. But Olmsted had an enormous and geographically widespread impact on America’s lasting ideas of what cityscapes should be.

As we bicycle today in Riverside Park in New York, feel the spray of Niagara Falls, picnic in the forest at Biltmore, hurry to class at Stanford University, climb a hill in Mount Royal Park in Montreal or fly a kite with our children in the Emerald Necklace in Boston, we may be unaware that we are visiting and enjoying places Olmsted had a hand in creating. We might not even be aware we are in a place that was planned or carved by a human hand at all.

Olmsted believed philosophically in the important restorative powers of natural beauty to help humans cope with harried and often depleting urban environments. In Central Park, and so many other public parks in other cities, he created pastoral places of respite where people of all classes could go for relaxation, exercise, inspiration, fun and renewal of their worn psyches. He brought idealized rural landscapes into urban environments and designed gathering places where people could meet friends and family and children could romp and play away from dangerous city streets, regardless of their economic backgrounds.

Aerial view of Central Park, circa 2000. Photograph by Carol M. Highsmith.

Olmsted became inarguably the most important landscape architect in America in the 19th century. Indeed, through his work he pioneered the entire field of landscape architecture that thrives today. His name and legacy continued on past his lifetime through the work of his stepson, John Charles Olmsted; his son, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr.; their Olmsted Brothers firm (1898–1961); and their many associates.

The digitized collection of the Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted, newly available from the Library of Congress, consists of approximately 24,000 items (over 47,000 images) of Olmsted’s personal papers, most of which were digitized from 60 reels of previously produced microfilm. While the collection spans from 1777 to 1952, the bulk dates from 1838 to 1903. The collection contains primary materials stemming from both Olmsted’s private and professional life. These include diaries, letters, printed reports, drafted manuscripts, clippings and other documentation.

A June 11, 1862, letter from Olmsted to his wife, Mary Cleveland Perkins Olmsted, about the horrors of war.

A May 20, 1865, letter from Calvert Vaux to Olmsted, urging him to commit to the field of landscape architecture.

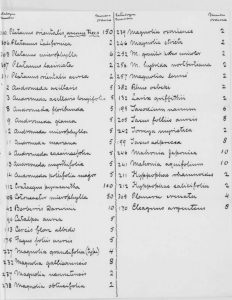

A plant order Olmsted placed on January 15, 1877, for the U.S. Capitol grounds.

Despite his fame, and the many projects, big and small, accomplished in the United States, Olmsted did not always know he would be a landscape architect. As a teenager, he learned surveying, mathematics and other skills by apprenticeship with farmers and educated men.

View from Central Park bridle path, 1984. Photograph by Jet Lowe.

As a young man, Olmsted traveled to England and the continent to view great art and architecture. He discussed innovations with master gardeners, botanists, civil engineers, water specialists, arborists and park managers. He would later draw on what he learned to help shape the aesthetics of cities, campuses, hospital grounds and residential communities across the United States. Before doing so, however, Olmsted worked as a clerk in New York, sailed to China on a merchant ship and taught himself about scientific farming by reading, observing and sitting in on lectures at Yale College.

As a young farmer himself, bankrolled by his father on small farms near Guilford, Connecticut, and on Staten Island in New York, he experimented in using organic methods and growing for local markets. He became a writer, a publisher and a journalist, a friend to antislavery advocates and reformers. He traveled on commission as a reporter through much of the pre-Civil War South, narrating to northern readers his opinions on agricultural economics and slavery.

Olmsted was working as an administrator at Central Park when the Civil War began. He turned his managerial skills to a leadership position with the wartime U.S. Sanitary Commission, reforming ways in which wounded and ill soldiers were transported and treated for battlefront maladies and attending to the public health of Union troops. He tried his hand briefly as the manager of a gold-mining estate in the foothills of the Sierras and investigated other business ventures in California.

Grounds of the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston.

It took the prodding of his friend Calvert Vaux to lure him back East to work in partnership on Prospect Park in Brooklyn after the war. Vaux advised Olmsted to make a commitment to landscape architecture as a profession, and the two paired on several important projects before striking out on their own.

During Olmsted’s later life, when the Olmsted firm was based at the Olmsted family’s Fairsted home in Massachusetts, the architect H.H. Richardson became another important friend and ally. Olmsted became deeply involved in planning the grounds for the U.S. Capitol. His crowning design achievements before he retired in ill health were the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago and the grounds of the Biltmore Estate in North Carolina.

Over the course of his career, Olmsted accepted private commissions and designed estates and institutions for wealthy clients, and he built a thriving business in doing so. But the heart of his work was in urban planning for public good and shared enjoyment.

Olmsted’s belief in the importance of creating and preserving natural spaces within cities extended to his commitment to wilderness preservation and forest conservation. As an original commissioner in California for what would become Yosemite National Park, Olmsted helped lay the groundwork for the idea of a national park system and the modern environmentalist movement. Fighting against overly intrusive commercial use, he argued that wilderness areas of extraordinary historic or natural consequence should be preserved for public use and be managed in ways that made it possible for ordinary citizens to visit for recreation and to witness the grandeur there, while the landscapes were protected to last as a public legacy into many future generations.

The Yosemite Valley from the Mariposa Trail, 1870s. Photograph by Carleton Watkins.