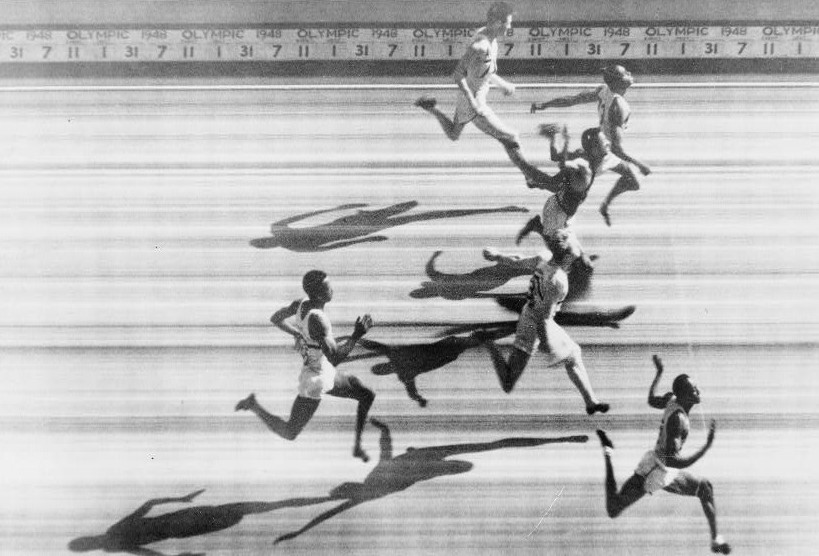

Harrison Dillard, bottom, wins the Olympic gold medal in a photo finish. Photo: Alamy Stock photo. Also in Prints and Photographs Division.

This post draws from an article by Megan Harris, a reference specialist in the Veterans History Project, in the Library of Congress Magazine. It’s been expanded here.

London, summer 1948. All eyes are on the first Olympic Games held since 1936. After years of war, countries from around the world meet not on the battlefield, but on the track, in the swimming pool, inside the boxing ring.

At Wembley Stadium, six sprinters crouch on the track for the finals of the 100-meter dash. The gun sounds and in 10.3 seconds it’s over. The race is so close that a photograph is used to declare the winner.

The image is striking. Six of the world’s fastest men, caught seemingly in mid-flight — none of their feet are touching the ground — are frozen in a furious burst of speed. They seem to be out-running their own shadows. It’s appears to be as much a ballet as it is a sprint.

But the photo makes it clear: William Harrison Dillard, at the bottom of the image, won the gold and takes the honorary title of the “fastest man alive.” His arms and hands are flung out and up, palms open, his right leg bent backwards at the knee, the toes of that foot pointing straight toward the heavens.

Fellow American Barney Ewell — who initially celebrated with arms raised, thinking he had won — took the silver. Panama’s Lloyd LaBeach edged the U.K.’s Alastair McCorquodale for the bronze.

Dillard’s feat was all the more stirring because, three years earlier, he had not been sprinting at a university or track club, but dodging mortar fire in Italy as part of the U.S. Army’s 92nd Infantry Division, a segregated unit known as the Buffalo Soldiers.

“I was extremely proud” of being a Buffalo Soldier, he said in a 2008 interview with the Library’s Veterans History Project.

As the 2021 Olympics get set to begin, it’s worth remembering that Dillard — along with Charley Paddock and Mal Whitfield — were among the armed services’ greatest Olympic champions in a long list of military and athletic greatness. The Department of Defense lists 19 members of the armed services participating in this Olympics.

Paddock, who served in the U.S. Army Field Artillery in World War I, won two golds and two silvers in the 1920 and 1924 Olympics. (You might remember him as the cocky American in “Chariots of Fire.”) He returned to the service during World War II and was killed in a 1943 military plane crash in Alaska. Whitfield, a member of the Tuskegee Airmen, and Dillard won a combined nine medals at the 1948 and 1952 Olympics, seven of them gold. Four of the golds belonged to Dillard; five of the total belonged to Whitfield. All three are in the U.S. Olympics & Paralympics Hall of Fame.

Dillard’s Olympics got off to a disastrous start. He failed to quality for the finals in his signature event, the hurdles, even though he was the world record-holder at the time (he hit several hurdles). He barely qualified for the 100 meters final and thus had to run in the far outside lane.

But perhaps most striking was that he had attended the same high school in Cleveland, Ohio, as Jesse Owens. Owens won four gold medals in the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, humiliating German leader Adolph Hitler and his ideal of Aryan supremacy. Dillard, about a decade younger than Owens, had been 9 when he had watched Owens, then a high school senior, run at East Technical High back home. He idolized Owens, vowing to grow up to be just like him.

Since the Olympics were cancelled due to World War II in 1940 and 1944, the 1948 Olympics were the first held since Owens had accomplished his feat. And so it was that the East Tech guys were, in consecutive Olympics, both dubbed the fastest men on the planet.

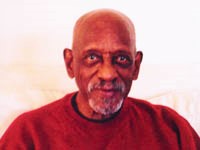

Harrison Dillard, at his home in Shaker Heights, Ohio, 2008. Photo: Veterans History Project.

Born in Cleveland, Dillard graduated from East Technical, then went to Baldwin-Wallace College (now Baldwin Wallace University) on a track scholarship. During his sophomore year, he was drafted and later assigned to the 92nd.

By 1944, he was in combat in Italy. For six months, the 92nd slowly advanced, liberating towns as they went. In his VHP interview, Dillard recalled mortar fire, minefields, the bravery of his comrades. He also remembered Italian civilians, their villages destroyed, begging U.S. servicemen for food.

With the end of the war, Dillard’s focus turned from survival to running. He would go on to being one of the greatest sprinters and hurdlers of his generation.

“I grew up physically in the service…but more than that it teaches you self-reliance and discipline,” he said in his VHP interview. “Military discipline is second to none.”

While stationed in Europe during the occupation, he won four gold medals at the G.I. Olympics. Gen. George Patton, whose papers are at the Library, had placed fifth in the pentathlon in the 1912 Olympics, was there. A reporter about the fiery general about Dillard’s performance. “He’s the best (expletive) athlete I’ve ever seen,” Patton responded.

He was the best athlete a lot of people ever saw. At the London Games, he won gold medals in 100-meter dash and the 4×100 relay. Four years later, at the Helsinki Games, he won the 110-meter hurdles and another relay — making him a four-time Olympic gold medalist, just like his idol, Owens. He’s the only man to win Olympic gold medals in the 100-meter dash and the 110-meter hurdles.

He returned to his hometown and spent the rest of his life there, well-known but not an icon. He spent most of his career as a manager in the business department of the Cleveland Board of Education, eventually retiring as department head in 1993. Fame never followed him very far, and he certainly never followed it.

When a reporter from The Undefeated visited him in 2016 for a story before the summer games in Rio de Janeiro, his Olympic medals were stored in a closet and there were no glory-days pictures or memorabilia on display. He was 93 years old. He didn’t consider himself a hero, but still saw Owens as one.

“He performed his athletic feat in circumstances where they were important, by throwing the lie of Aryan supremacy right in Hitler’s face and in his house,” he told The Undefeated. For himself, he said, his athletic achievements didn’t carry the same symbolism, and, at the end of the day, he didn’t think running fast was all that important in the scheme of things.

He died in 2019. He was 96.

Grit and resilience are among the qualities that make Olympic athletes great — many overcome formidable challenges just to reach the games. It’s even more difficult to survive the rigors of military service and combat to arrive at the medals podium.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.