This is a guest post by Julie Miller, a historian in the Manuscript Division.

Martha Washington, in an unfinished portrait by Gilbert Stuart. Theodor Horydczak Collection. Prints and Photographs Division.

In December 1793, Martha Washington bought a new book by Mathew Carey called A Short Account of the Malignant Fever Lately Prevalent in Philadelphia. The following February she bought a similar title, A Short Account of the Yellow Fever in Philadelphia, for the Reflecting Christian, by Henry Helmuth.

Her interest was personal. In the summer of 1793 when a devastating yellow fever epidemic hit Philadelphia she was in the city, then the U.S. capital, as the wife of the president. Carey, a publisher and bookseller, was also there. He joined a committee that helped the poor and sick who stayed behind when the wealthy fled. The Rev. Helmuth stayed to care for his congregants. The Washingtons remained in Philadelphia through the summer, but on Sept. 10 they left, as did nearly every member of city, state, and national government.

Yellow fever is a frightening disease. Benjamin Rush, a prominent Philadelphia doctor and author of another book about yellow fever, noted his patients’ chills and fever, yellowed skin, stomach pains, nausea, headache, sore eyes and delirium.

Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson wrote: “It is called a yellow fever, but is like nothing known or read of by the Physicians. The week before last the deaths were about 40. the last week about 80. and this week I think they will be 200. and it goes on spreading.”

Carey described how “acquaintances and friends avoided each other in the streets, and only signified their regard by a cold nod. The old custom of shaking hands fell into such disuse, that many were affronted at even the offer of the hand.” Carey estimated that out of a population of 50,000, about 17,000 left the city and 4,000 died. Later estimates put the death total as high as 5,000.

Between 1793 and 1805, waves of yellow fever attacked northern ports in the U.S. Then the disease retreated south, where it persisted through the end of the 19th century. At the turn of the 20th century, a time of great advances in bacteriology, scientists discovered that yellow fever was transmitted by the bite of an infected mosquito. This eventually led to a vaccine, although the disease is still endemic in parts of Africa and South America.

The yellow fever epidemics that struck American cities soon after the birth of the nation left a powerful mark in the historical record. That mark is visible in books, newspapers, maps and more at the Library, but especially in the papers of members of George Washington’s administration. Leaving Philadelphia in 1793, Secretary of War Henry Knox wrote Washington that “the alarm of the people in all the Towns and villages on the road, and at New York, on account of the prevailing fever is really inexpressible.”

The president, at home at Mount Vernon, described Philadelphia as “now almost depopulated by removals & deaths.” Thomas Jefferson commented snidely about treasury secretary Alexander Hamilton, who was sick with the fever: “A man as timid as he is on the water, as timid on horseback, as timid in sickness, would be a phaenomenon if the courage of which he has the reputation in military occasions were genuine.”

Politics filtered into debates about yellow fever.

“Contagionists” were likely to be Federalists who advocated restored trade with Britain and feared revolutionary France. They believed that yellow fever arrived on ships with refugees from France and its West Indian possessions. Pro-French Republicans, meanwhile, believed yellow fever was not contagious and that its causes were local.

Public officials, uncertain what to do, ordered quarantine and sanitation. Philadelphia’s free black citizens, including church leaders Absalom Jones and Richard Allen, were forced to fight back prejudice during the epidemic.

Benjamin Rush, 1802. Portrait: Charles Balthazar Saint-Mémin. Prints and Photographs Division.

Doctors were divided about treatment. Rush favored purging and bloodletting, while David Hosack and Edward Stevens, physician friends of Alexander Hamilton, believed in a milder treatment of quinine, wine and cold baths. Rush, whose methods were controversial, sighed, “I shall sooner or later be believed and forgiven.”

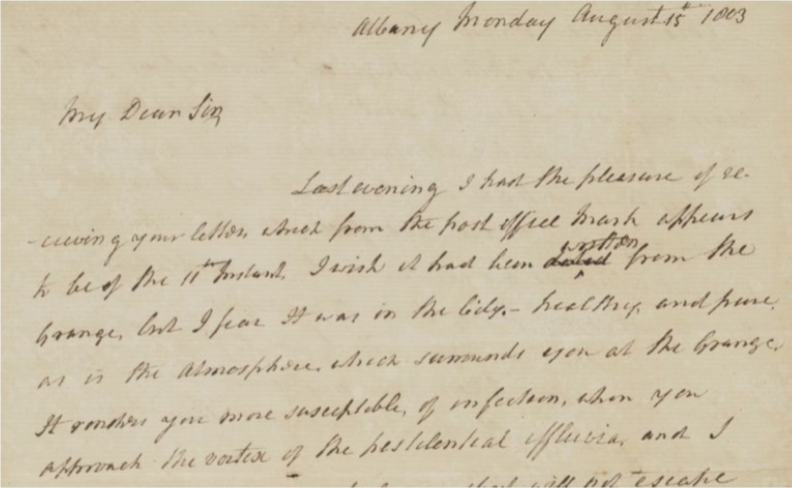

Some of the most anxious testimony is in letters from Philip Schuyler to his daughter, Elizabeth Hamilton, and her husband, Alexander. As yellow fever threatened Manhattan in 1803, Schuyler, a Revolutionary War general and New York politician, wrote Elizabeth that he was “under great anxiety for the safety of my dear Hamilton.” He warned his son-in-law to stay out of “the vortex of the pestilential effluvia.” “I cannot, my dear sir,” he pleaded, choosing his words carefully to best express his emotion, “describe how much I dread apprehend from your exposing yourself to pestilence.”

Letter, Philip Schuyler to Alexander Hamilton, Aug. 15, 1803. Alexander Hamilton Papers, Manuscript Division.

By December 1793, the disease had retreated from Philadelphia. Thomas Jefferson wrote his daughter, “This place being entirely clear of all infection, the members of Congress are coming into it without fear.” George Washington was back, Jefferson reported, but his wife was not. Because so few of Martha Washington’s letters survive, we have to rely on fragments of information, such as this “small news,” as Jefferson called it, or the record of her book purchases, to learn how she reacted to the yellow fever epidemic.

Now that we are living through something similar, it is not hard for us to imagine her alarm – or her relief when it was over.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.