Betty Bormer, who was freed by the military order that founded Juneteenth. Fort Worth, Texas. June 26, 1937. Photo: Works Progress Administration. Prints and Photographs Division.

Journalism is often called the first draft of history. As any writer can tell you, first drafts are often messy.

So on this momentous day, the first federal holiday of Juneteenth, let’s look at how 19th-century media covered the birth of what would become the nation’s official holiday marking the end of slavery. That was the June 19, 1865, order by Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger in Galveston, Texas, that abolished slavery in that state, the last Confederate holdout.

Granger did not bury the lead. He established the legal authority to assume military command in the state and named his staff in two brief general orders, or military proclamations. Then he cut to the heart of the matter in “General Orders, No. 3.”

“The people are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property, between former masters and slaves.”

Clear and concise. Not a word wasted. Black people in Texas, the last in America to find out that the Emancipation Proclamation applied to them, were out of bondage. Slavery was dead. A terrible era was over.

Today, we mark that announcement as a very big deal. The nation, founded on the ideal of equality, fought the deadliest war in its history over slavery, yet waited 156 years to officially mark the demise of the institution. There’s a lot to unpack in that, and we, as a nation, continue to do so.

But how did newspapers report it at the time?

By and large, they didn’t. Or just barely.

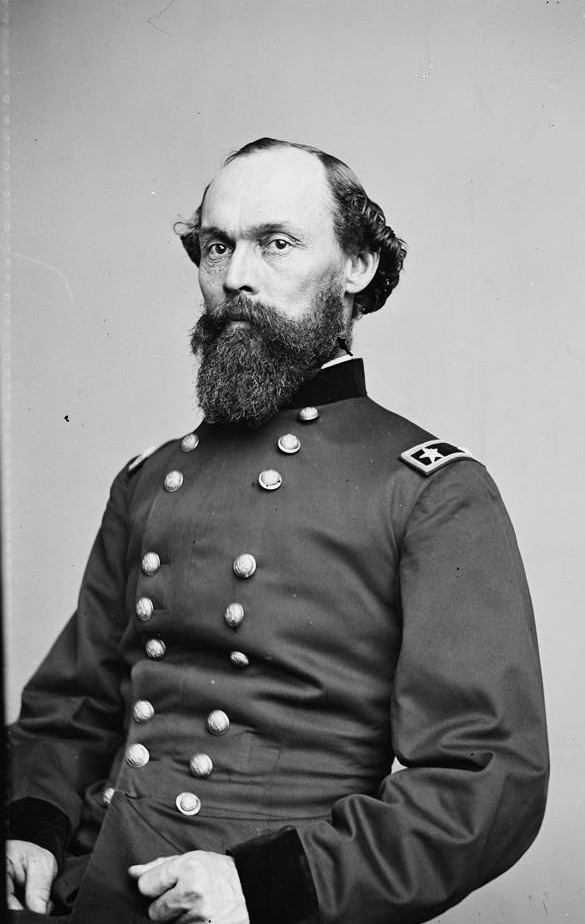

Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger. Photo: Brady’s National Photographic Portrait Galleries. Prints and Photographs Division.

The Galveston Tri-Weekly News, the Galveston News and the Houston Telegraph all reported Granger’s orders on June 20. These notices would, in the coming weeks, be picked up by other newspapers across the country. “The Slaves Declared Free,” ran a small front-page headline in the New-York Daily Tribune on July 7, prioritizing that declaration above the other four that Granger issued that day.

But by and large, most newspapers that can be found in the Library’s Chronicling America archives and in other databases available on-site show that most newspapers paid scant attention. The slavery order, if mentioned at all, was often just a one-sentence notice, deep in the sea of tiny type that characterized newspapers of the era, a pointillist’s dot in a newspaper mural.

Surprisingly, the only major dispatch from Galveston that week, which focused on the mood of the city, didn’t mention the orders.

“Jatros,” a correspondent for the New-York Daily Tribune, on June 20 filed a first-person account of walking through Galveston. He seemed unaware the order had been issued the previous day. “Galveston is a city of dogs and desolation,” Jatros wrote, in a colorful piece that would take two weeks to be printed in his own paper, then be republished by several others. He noted that “colored” Union troops kept the peace, but still referred to the local black population as “slaves.”

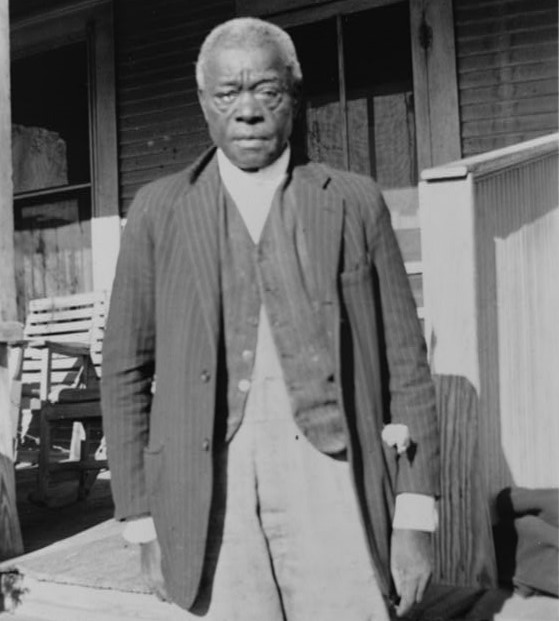

William Moore, who was freed by the military order that founded Juneteenth. Dallas, Texas. Dec. 21, 1937. Photo: Works Progress Administration. Prints and Photographs Division.

Jatros noted that livestock roamed the streets at will, that the city’s low-slung houses were often painted yellow, that the stores were dingy and devoid of merchandise, that the people were “stunted and scraggy” like the local trees. It was, by far and away, the most in-depth report from the place where Juneteenth originated, and yet it did not note that Black people were now free.

On Saturday, July 1, the weekly Dallas Herald printed all of Gordon’s orders but buried the item on the paper’s second page, along with noting that there had been a fine rain recently. On July 8, the Cincinnati Daily Inquirer reported the “all slaves are free” passage in a news round-up under the headline of “Afternoon Telegraph From the South-West.”

While all this might today seem a historical omission, that wasn’t necessarily true at the time.

Almost everyone outside of Texas already knew that slavery was over. Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, freeing enslaved people in the secessionist states, had gone into effect on January 1, 1863. The Thirteenth Amendment, abolishing slavery, had passed the U.S. Congress in January, 1865, and was being ratified by the states. Robert E. Lee, the Confederate military leader, had surrendered his army at Appomattox, Virginia, on April 9, 1865.

By June, Lincoln had been assassinated and the trial for his killers was underway. Debate raged about the fate of former Confederate troops and politicians. The new president, Andrew Johnson, was in the midst of appointing provisional governors to take control of the rebellious states.

In this turbulent, pell-mell of violence and the after-shocks of four years of war, the fact that a little-known military officer read a proclamation reiterating that slavery was indeed over in one far-flung state was not exactly earth-shaking.

“While it is difficult to know precisely why Gen. Granger’s General Orders No. 3 did not receive more press coverage, it coincided with a time when other national news likely took precedence for newspaper editors,” says Michelle Krowl, the Library’s Civil War and Reconstruction specialist.

Besides, whites in Texas did not exactly regard Granger’s orders as good news, as a New York Times piece on July 16 made clear. The paper reported that nine days after Granger’s orders were issued, the mayor of Galveston called a meeting of the city council to address the “altered condition of the colored population, which required new regulations for the protection of the citizens.”

Granger took quick action. The next day, he decreed that “No persons formerly slaves will be permitted to travel on the public thoroughfares without passes or permits from their employers, or to congregate in buildings or in camps at or adjacent to any military post or town.”

In less than 10 days after obtaining “absolute equality,” Black Texans were ordered – by the federal government, their supposed liberators – to get permission from their former owners to so much as walk down the street. It was a harbinger of the false promises of Reconstruction.

Still, for the one group of people who did regard Granger’s order as a revelation — Black Texans — the news was earth-shaking. They staged celebrations on the first anniversary of Granger’s order and, by 1872, a group had pooled resources to buy what is now known as Emancipation Park in Houston for their observation of what became known as Juneteenth.

It seems plain that is the spirt which today, a century and a half later, marks this as a federal holiday. Juneteenth is not a holiday simply because of Granger’s order. It exists because black Texans celebrated it for years, decades, more than a century, in the teeth of Jim Crow segregation and racist violence, in the unyielding belief that the United States might someday become a land of the free.

Anderson and Minerva Edwards, who were freed by the military order that founded Juneteenth. Marshall, Texas, Aug. 3, 1937. Photo: Works Progress Administration. Prints and Photographs Division.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.