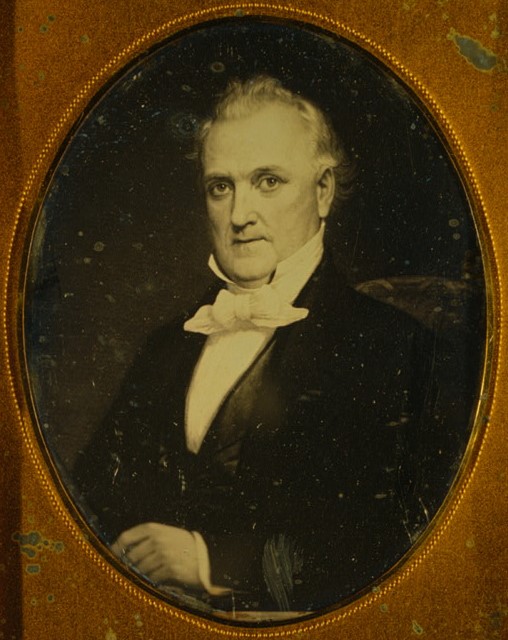

President James Buchanan’s name was used to lend credibility to the hoax. Prints and Photographs Division.

This is a guest post by Candice Buchanan, a reference librarian in the local history and genealogy section of the Main Reading Room. Her most recent piece was a guide to finding female suffragists in family histories.

Ninety years ago, as the Great Depression drained hopes and finances across the country, a Texas grocer named Lorenzo D. Buchanan stepped forward with one of the great hoaxes of 20th-century American pop-culture life, a genealogical fabrication that continues to resonate today.

Lorenzo, who ran a modest store in Houston, told reporters a whopper: The $850 million estate of one of his ancestors was ready to be distributed among eligible heirs who could prove kinship.

This ancestor, he said, was William Buchanan, who had left the bequest tied up in recently expired, 99-year land leases across the country, which included prime Manhattan real estate. William was said to be a cousin of former President James Buchanan, which lent the story credibility.

Genealogical pandemonium ensued.

Americans went bananas. Everyone named Buchanan, or related to someone named Buchanan, or who thought they might possibly have a distant cousin twice removed was suddenly researching Buchanan history. Others just made up connections and hoped nobody noticed.

It went on for five incredible years, even after Lorenzo and his lawyer said the story was completely fabricated, even after judges and economists said the estate didn’t exist, even after genealogical experts at the Library said there were no family ties to claim. Then it resurfaced from generation to generation, as the aging children of parents who had been taken in by the scam came across old paperwork in attics, family Bibles, scrapbooks that showed…they could inherit millions!

I know this because my family was caught up in the hysteria, too.

I came across my family’s claim as a teen in my small Pennsylvania town. It didn’t come with a warning label. There was just paperwork, waiting to be notarized, that showed we were eligible heirs. It was incorrect and had been assembled by an apparently unscrupulous agent, but it certainly looked official.

That happened all over the U.S. when the hoax was at its height and people were desperate for any sort of financial hope.

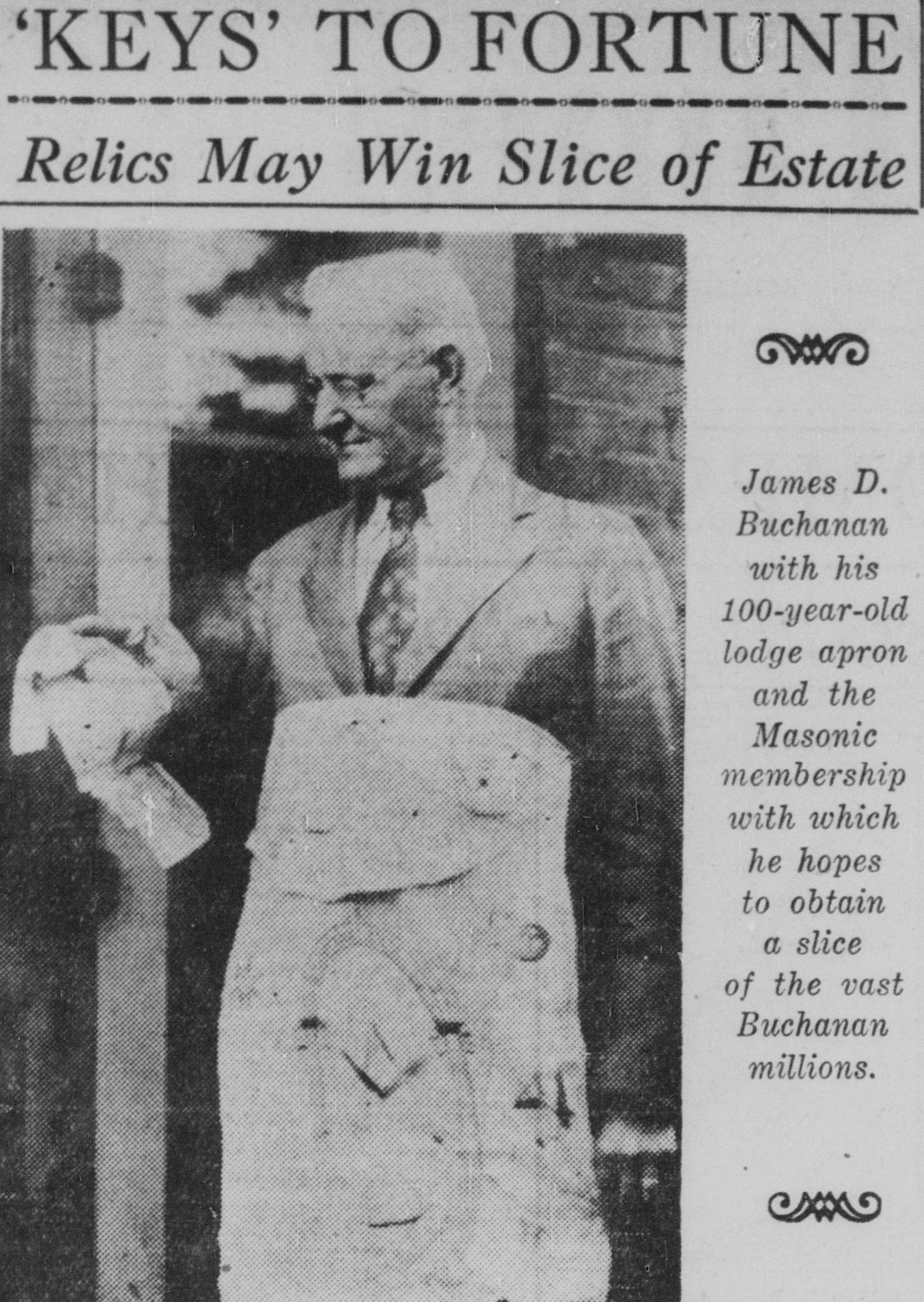

James Buchanan of Indianapolis thought he was heir to the multi-million dollar estate. Indianapolis Times, June 2, 1931. Chronicling America.

Newspapers across the country were filled with sensational stories about a local family who was anticipating their enormous inheritance any day now.

The Library was inundated with Buchanan genealogical requests. Overwhelmed librarians prepared a standardized memorandum, in which they explained that the most reliable records in our collections did not support a relationship to the fabled William Buchanan. Nor could they be sure that such a person had even existed.

At the same time, New York state surrogate judges, who presided over wills and estates, faced an onslaught of inquiries from people insisting to see a probate file of which the court had no record. The judges implored the state’s governor (and soon-to-be presidential candidate), Franklin D. Roosevelt, to intervene.

It should have ended then. Lorenzo, who had grown weary of the hoax, said that he had “ceased all operations in connection with the supposed estate.” Newspaper articles show that he even signed an agreement with the U.S. Postal Inspector to return — unopened — the thousands of letters people were sending him.

And yet, the hoax just gained steam. Mysterious “agents” suddenly appeared, saying they could help aspiring heirs file claims. In New York state, fees ranged from $15 to $250 — about $280 to $4,700 in 2021 dollars.

The issue came to a final showdown in a civil suit against Lorenzo Buchanan in 1936. It was thrown out of court, with his attorney mocking plaintiffs for having believed his client’s tall tale. Buchanan cited poor health, never appeared in court and never explained why he had concocted the hoax. He likely made some money off the episode, but it wasn’t the type of scam, or Ponzi scheme, from which he would have pocketed much.

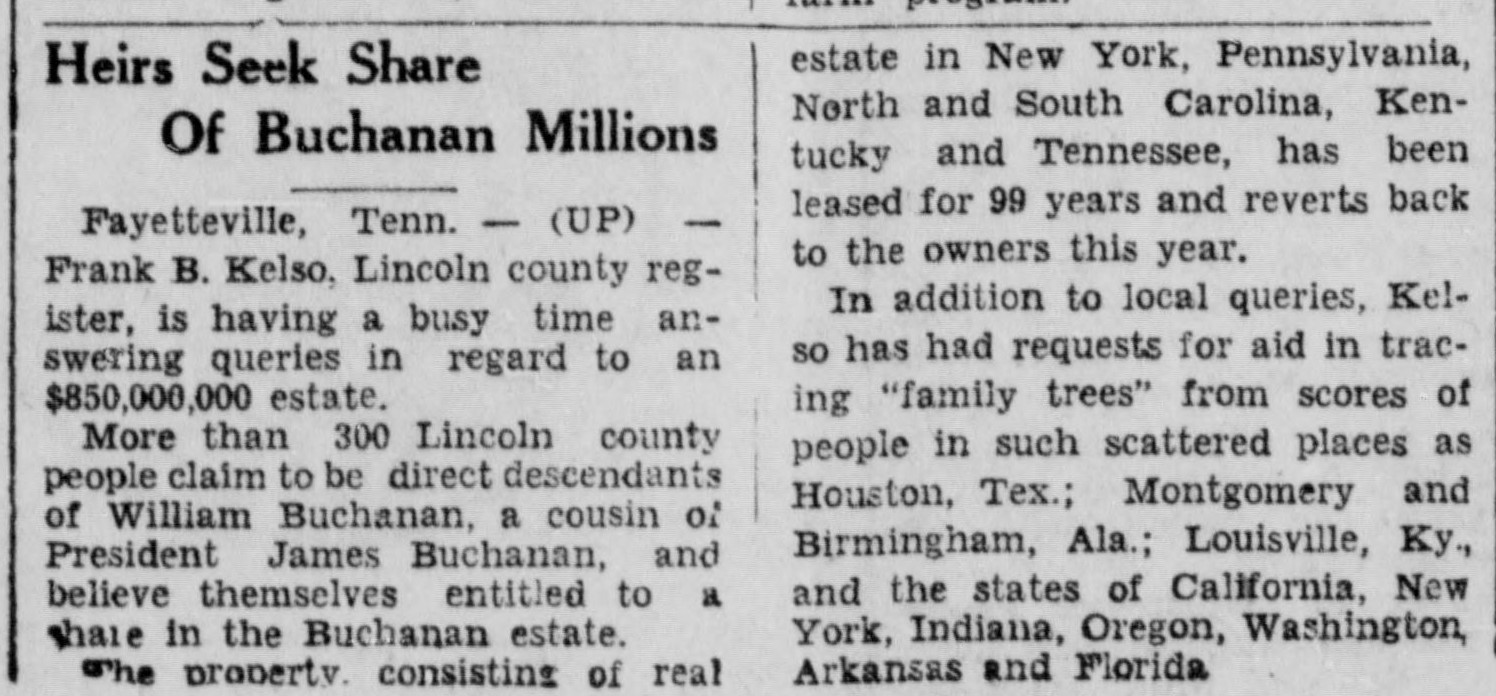

More than 300 people in Lincoln County, Tennessee, claimed to be descendants of the fictional William Buchanan. The Frontier, Holt County, Nebraska. August 20, 1931. Chronicling America.

Why had so many people believed in something that was so easily proven false?

Part of it is natural, as any genealogist can tell you. There is an inherent curiosity that can make us wonder if we are related to people who share our name. No scam is required to draw potential descendants towards branches of the family tree that ascend to celebrity ancestors such as heroes, leaders, founding fathers or nobility. The problem with many of these trees is that they are intended to connect living generations to a particular ancestor rather than to an accurate ancestor.

The Buchanan estate not only combined name recognition with celebrity, it also offered a mirage of financial relief during a period of extreme economic hardship. Buchanan family trees, many of them false, began to grow toward the former president. Since he was a bachelor with no known children, Buchanans attached themselves to the President’s siblings or to his father’s siblings, allowing more room for false hopes and fabricated claims.

“The Buchanan Book,” published in 1911, includes a small section devoted to the lines of American Buchanans. During the hoax, people used the book as a guide, but often mistakenly (or fraudulently) inserted one of the included names into their own family tree as a distant relation of the former president. Presto! You had a legitimate-looking family tree that showed you could inherit millions. That was the type of document I came across in my family’s papers so long ago.

I was hardly alone in coming across these kinds of claims. In the 1960s, three decades after the hoax was exposed, Library records show congressmen were still asking the Library for help in tracking down Buchanan claims sent in by constituents.

Today, genealogists are unlikely to believe they can still inherit from the alleged 1930s estate, but they do get misled by the fake family trees handed down to them. It’s easy to see why.

Family heirship claims leave behind documents that have the appearance of authenticity. They may be notarized, published, or written in a beloved grandmother’s hand. Then these family papers are inherited by unsuspecting descendants.

One of the reasons these genealogy mistakes are hard to correct is because genealogy is so personal. It’s not just history, it’s our history. We bond to it, especially if it’s a story that has been shared in our families. If we’ve been told that we have a famous ancestor or we come from a certain part of the world, those things get ingrained in our identity. It’s very hard to help people change their minds because it’s not just in their minds, it’s in their hearts.

Fortunately, genealogists can overcome these obstacles by doing their own research. Climb the family tree by beginning with yourself and working backwards one generation at a time. Collect and evaluate records, interview relatives and address conflicts. Be mindful of facts that don’t fit – and be wary of any claims to fame or fortune!

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.