A little more than a year ago, Hurricane Harvey hit the Texas coast as a category 4 storm, bringing damaging rain and flooding. Less than a month later, Hurricane Maria struck Puerto Rico with heavy downpours and sustained winds of 155 miles an hour – only two miles an hour shy of a category 5 hurricane. Today, people in both Texas and Puerto Rico continue to grapple with the aftermath of the storms.

More than a century earlier, before satellites and intricate computer modeling detected impending storms, residents of Galveston, Texas – then the state’s largest city – were caught almost completely by surprise by a category 4 hurricane.

The most lethal weather disaster in U.S. history, the hurricane hurtled into the city on September 8, 1900, with devastating results: an estimated 8,000 people died, and the city was leveled, never to recover its former status. Before the hurricane, the fast-developing port city was seen as a potential rival to New Orleans or San Francisco.

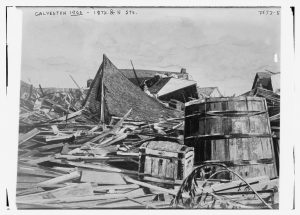

A news photo showing the aftermath of the 1900 Galveston hurricane.

I first learned about the hurricane when I wrote about the Library’s digitization of historical Sanborn fire insurance maps. Created to help insurers estimate fire hazards, Sanborn maps document details such as street names and widths and the location of public buildings, churches, businesses and dwellings. As an example of how researchers use the maps today, a colleague in the Geography and Map Division mentioned to me that Erik Larson, author of the 1999 best-seller “Isaac’s Storm: A Man, A Time and the Deadliest Hurricane in History,” consulted an 1899 Sanborn map of Galveston to reconstruct what the city was like when the hurricane struck. The map is one of many Library resources that offer a glimpse of the storm’s scale and human cost.

1899 Sanborn map of Galveston showing the city’s layout before the hurricane.

Today, the National Weather Service uses intricate computer modeling, a network of ground- and ocean-based sensors, satellites and hurricane-hunter aircraft to predict the tracks of hurricanes and their intensity. In 1900, the situation was very different. Meteorology was an emerging science, and the Texas Section of the new U.S. Weather Bureau had opened only nine years before.

The bureau’s Washington, D.C., office sent a telegram to Isaac Cline, Galveston’s chief local forecaster, on September 7, warning only of a tropical storm in the Gulf of Mexico that was moving slowly northwest and likely to cause high winds and heavy rain, recounts Erik Larson in “Isaac’s Storm.”

By the morning of September 8, however, worrisome signs caught Cline’s attention: when seawater started washing onto streets bordering the Gulf, he alerted Washington that “such high water with opposing winds” had never before been seen. Still, unsuspecting residents welcomed the storm’s early stages. Children navigated the rising water in homemade rafts, and hundreds of people went down to beach to watch the spectacular surf.

By the time everyone realized the storm’s danger – it roared ashore late in the day, bringing winds of more than 120 miles an hour – it was too late to do anything. Larson envisions initial devastation around 6:30 p.m.:

The sea had erected an escarpment of wreckage three stories tall and several miles long. It contained homes and parts of homes and rooftops that floated like the hulls of dismasted ships; it carried landaus, buggies, pianos, privies, red-plush portieres, prisms, photographs, wicker seat-bottoms, and of course corpses, hundreds of them.

Isaac Cline had built his house, three blocks north of the Gulf, on stilts to withstand extreme weather. But the hurricane’s severe winds and rising waters – the storm surge exceeded 15 feet – were too much. When the house collapsed, Cline, his three daughters and his brother survived by clinging to floating wreckage; Cline’s wife, pregnant with their fourth child, drowned.

As word of the devastation spread, people from outside started arriving to help, among them Clara Barton, famed Civil War nurse and American Red Cross founder. Larson consulted her papers at the Library to tell the story of the storm’s aftermath. “Destruction here is beyond human conception of those who have not seen it,” Barton wrote in a September 19, 1900, telegram.

Two women search through wreckage.

To document the storm’s effects, Thomas Edison’s film company sent a team of photographers. “Arriving at the scene of desolation shortly after the storm had swept over that city, our party succeeded, at the risk of life and limb, in taking about a thousand feet of moving pictures,” Edison’s film catalog reads. One film depicts the Galveston Orphan’s Home. Although badly damaged, it fared better than Saint Mary’s Orphan Asylum, located just off the Gulf, where dozens of children and their caretakers died.

{mediaObjectId:'E3628D8949A7047AE0438C93F028047A',playerSize:'mediumStandard'}

In other documentation, the Library’s Prints and Photographs Division has dozens of photographs from different sources showing the storm’s destruction.

Not surprisingly, newspapers covered the hurricane in great detail. Check out a sampling of accounts in the Library’s collection.

On a more hopeful note, the Library also has photographs of the reinforced concrete seawall built after the hurricane to protect Galveston. Seventeen-feet high and initially more than three miles long – it now extends over 10 miles – the seawall has helped to repel Gulf winds and water for more than a century now, reducing damage from the many hurricanes that have struck Galveston since the great storm of 1900.

Today, the city’s Strand – its historical warehouse and commercial trade district, rescued and rebuilt behind the seawall – is a National Historic Landmark and a favorite destination of tourists from around the world.