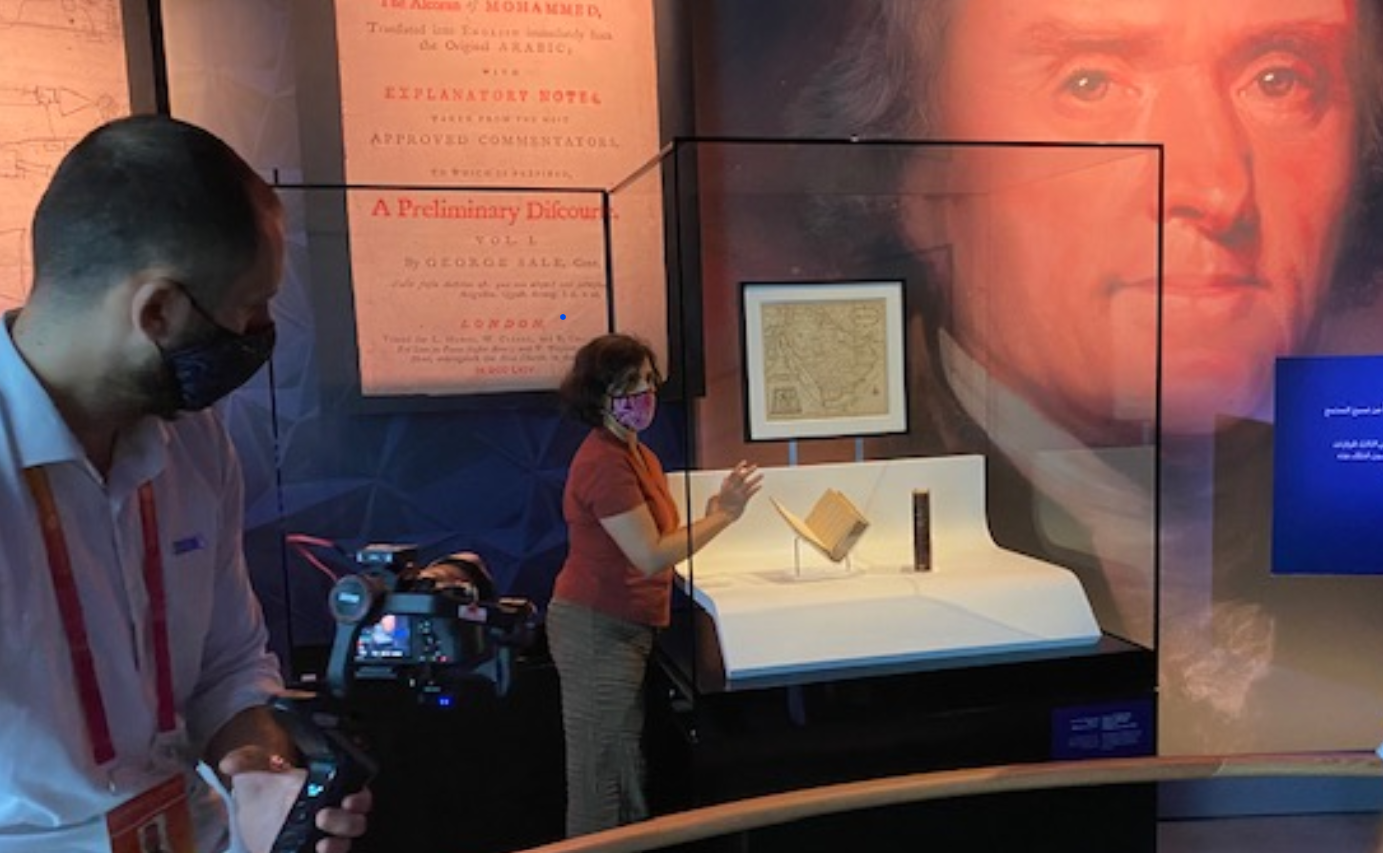

Yasmeen Khan (center), head of the Library’s Paper Conservation Section, helps install Jefferson’s copy of the Koran in the U.S. exhibit in Dubai, UAE, as USA Pavilion photographer Ibrahim Rahma films. Photo: Steve Hersch.

Thomas Jefferson’s copy of the Quran, one of the treasures of the Library, is making its first-ever appearance in the Middle East this month, debuting at the glittering World Expo in Dubai in the United Arab Emirates.

Jefferson’s English translation of the Islamic holy book is one of the stars of the Expo’s U.S. Pavilion, themed “Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of the Future,” a riff on Jefferson’s famous phrase from the Declaration of Independence. Library staff installed the two-volume, 1764 copy of the Quran in a secured case as the first object on display after guests emerge from a sound and light experience that showcases the U.S. founding principles, particularly its innovations. Jefferson and the Quran are the first example of those goals, followed by some of the works of Benjamin Franklin and Alexander Graham Bell.

“Thomas Jefferson was widely interested in and curious about a variety of religious perspectives,” said Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden. “Our nation’s history is a rich and beautiful reflection of the diverse ideas, cultures and religion of its citizens. The Library of Congress, the nation’s library, is a symbol to free access to information and the role it plays in a knowledge-based democracy that we share.”

The Expo, delayed for a year due to COVID-19 but still billed as Expo 2020, is a continuation of the 170-year-old tradition of international exhibitions that began as a means of sharing, if not showing off, each nation’s technology and cultural gems.

The first such event was held in London in 1851, billed as “The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations,” the brainchild of Prince Albert. He wanted to show off Britain’s industrial gains to the world (particularly Europe) as a means of building trade and British power. It was held in an iron-and-glass structure so striking that it was called the Crystal Palace.

Stereograph view of the Crystal Palace. Marian S. Carson collection, Prints and Photographs Division.

It was a magnificent success, with more than 6 million people attending, launching a plethora of such fairs through the 19th century until today. These displays were mixed with great technological wonders – nascent telephones (and mobile phones a century later), televisions, the Ferris Wheel and so on – but also, in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the overt racism and colonialism of the era, as people from developing nations were often exhibited as “natives.”

The event in Dubai features exhibits from 192 nations as well as dozens of corporations and runs until next March. The Jefferson Quran will be on display for three months, an unusual stay for the type of item the Library usually only loans to other permanent museums, libraries or cultural institutions.

The book, and a framed map of Mecca that came with it, traveled in a custom-made wooden crate with four inches of padding and customized trays with more padding, along with a sensor that detects vibrations and temperature changes. Library conservation and security staffers, along with police and an international freight company that specializes in fine art shipping, secured the crate en route.

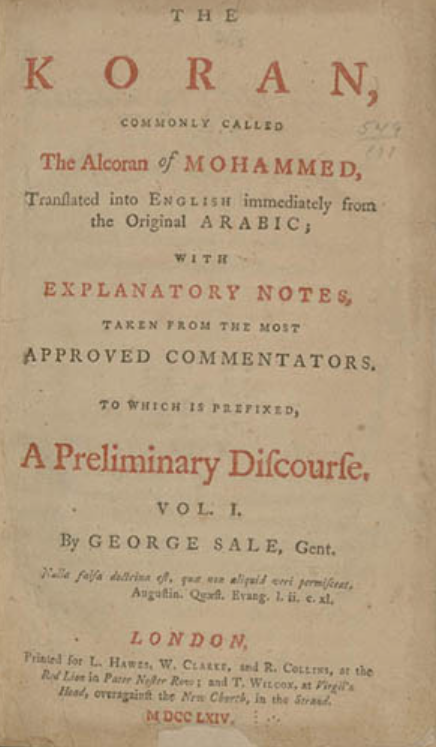

Title page of Jefferson’s copy of the Koran. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

Jefferson bought his copy of the Quran in 1765 in Williamsburg, when he was 21 or 22, studying law. The two volumes are a second edition of the influential 1734 translation by George Sale, with Jefferson’s copy published in London in 1764.

Jefferson, who had an abiding interest in world religions, may have also valued the Quran as a comparison for legal codes across the world. Further, some of the enslaved Africans brought to America were Muslims, as the Library documents in the writings of Omar Ibn Said. Jefferson, who enslaved more than 600 Black people over the course of his life, may well have had firsthand experience with members of the faith.

He would go on to amass the largest collection of books in the United States in the early 19th century. After the British burned the Capitol building and the Library of Congress during the War of 1812, Jefferson sold his collection of 6,487 volumes to Congress in 1815 for $23,950. Many of his political opponents voted against the purchase, citing Jefferson’s wide-ranging interests as an “infidel philosophy” and that the books were “good, bad, and indifferent … in languages which many can not read, and most ought not.”

The Great Hall in the Thomas Jefferson Building. Photo: Shawn Miller.

The collection was so large that it took 10 wagons to carry them from his Monticello estate to Washington. It is regarded as the founding of the modern Library, and Jefferson as the Library’s patron saint, with the Library’s main building bearing his name. A fire on Christmas Eve in 1851 destroyed two-thirds of Jefferson’s collection, but the Quran was one of the volumes that survived. The book was rebound by the Library in 1918.

It endures as powerful symbol of Islamic faith in the country ̶ U.S. Rep. Keith Ellison, who in 2006 became the first Muslim elected to Congress, took his oath of office on Jefferson’s Quran.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.