Giles McCoy. Veterans History Project.

For Independence Day, we offer the lead piece from the Library of Congress Magazine July/August 2020 issue, “Voices of War.” Several other pieces from that issue will follow during the coming weeks.

War tests the limits of what a human can endure.

It asks those who serve to do unimaginable things — to leave loved ones behind for years at a time, to suffer extreme conditions and deprivations, to risk life and limb, to kill or be killed.

Giles McCoy lived that.

During World War II, McCoy fought with the 1st Marine Division at Peleliu, Iwo Jima and Okinawa — three of the most brutal battles in Corps history.

He got shot by a Japanese sniper on Iwo and survived a kamikaze attack at Okinawa. The worst came later. In July 1945, his ship, the Indianapolis, was torpedoed and quickly sank, taking 300 sailors and Marines down with it.

McCoy and about 800 others floated in the open Pacific for four days, most with only a life jacket, trying to stay alive. Some drowned. Some died of dehydration and exposure. Some, in a state of delirium, killed themselves. Some died a different death.

“We had sharks everywhere,” McCoy would recall. “The first couple of days there was probably a hundred sharks around us all the time. A couple of guys got hit by sharks and got taken down.”

Of the 1,196 men aboard the Indianapolis, only 316 survived — one of the worst disasters in U.S. Navy history. But McCoy lived, and his story today is part of the collections of the Veterans History Project (VHP), a program of the Library of Congress.

Congress created VHP in 2000 to gather, preserve and make accessible the firsthand remembrances of U.S. war veterans. Its collections chronicle the experiences of men and women who, like McCoy, fought World War II — years of hardship, heartbreak, courage and loss written down in letters and journals and in makeshift diaries cobbled together at prisoner-of-war camps across Europe and the Pacific.

George Pearcy. Veterans History Project.

George Pearcy was serving in an Army artillery unit in the Philippines when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. The Philippines soon were overrun too, and Pearcy was captured and held in a succession of POW camps.

There, he kept a diary, now held by VHP, on whatever he could find: old maps, hospital forms, labels peeled off food cans. On those scraps, he chronicled all he saw — beatings, decapitations, escape attempts, the turning of prisoners against each other to survive.

In 1944, the Japanese began evacuating POWs, Pearcy among them, aboard “hell ships” — freighters known for their terrible conditions. Some were so packed that prisoners barely could lie down. Temperatures often hit 120 degrees, the hot, humid atmosphere fouled by the stench of human waste and unwashed bodies.

A U.S. submarine torpedoed Pearcy’s ship, and only nine prisoners survived. He wasn’t one of them. Pearcy’s story is known today only because, fearing the worst, he divided up his diary among comrades who remained behind. Half the diary made it back to his family in the care of a soldier from Utah — Robert Augur, whose own POW diary is held by VHP.

Such tragedies were deeply felt back home. The war separated loved ones for years at a time, and letters often were the only means of communication.

Robert Ware joined the Virginia National Guard in 1940 and was assigned to the Army’s 104th Medical Battalion. Two days before D-Day, his wife Martha wrote to him, pondering their lost years together and their uncertain future:

“Do you know the quotation that says, ‘Tho a man be dead, yet shall he live.’ I think I’ve come to know what that means these two years as I watched my 20s slip away and realized that we have never yet had our chance and have no hope of it for a long time.

“I am only living on the faith that God will give me a chance before it’s too late — a chance at a permanent home, children, a certain amount of financial security and above all a chance to live with the man I love so devotedly, so completely — my husband.”

Ware never saw her letter — he was killed going ashore with the first wave at Normandy.

VHP collections preserve countless such stories of survival and heartbreak.

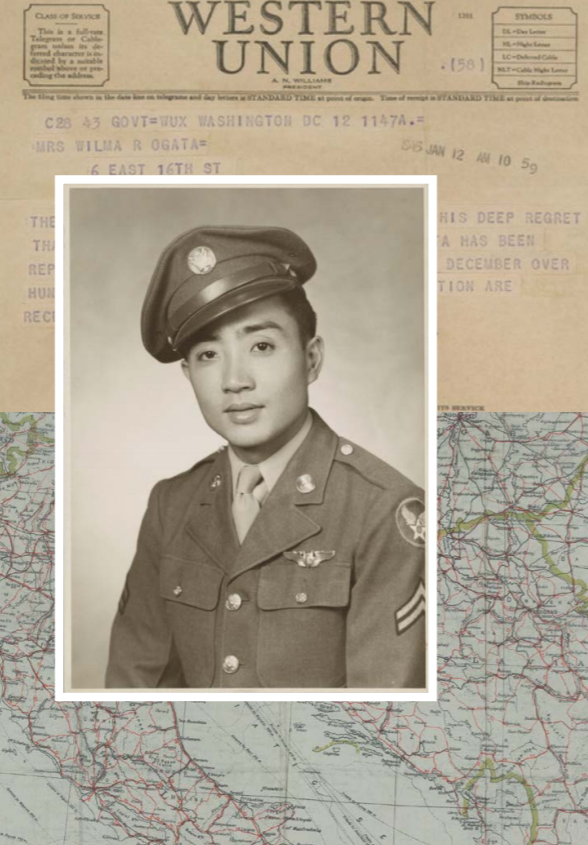

Army Air Forces Sgt. Kenje Ogata, picture set over a telegram informing family of his plane being shot down and a map he used to get back to Allied territory. Photo layout: Ashley Jones. Material: Veterans History Project.

Kenje Ogata, a Japanese American turret gunner in a B-24 bomber, got shot down over central Hungary, took refuge with a local family, reunited with his crewmates and traveled by foot, ox cart and train to Soviet-held Romania, then flew back to his base and the war.

Army Sgt. A. William Perry served in the segregated 92nd Infantry Division fighting in Europe. In an oral history, he recalled the difficulty of driving the Germans from mountainous Italy — an ideal place, he noted, to fight a defensive war.

The Germans would chop down trees and place them as obstacles in front of you, mine the fields next to the roads, aim machine guns and artillery down the roads at whoever moved up them. “If you came up the road,” Perry said, “you didn’t have a chance.” In its first action, his unit lost 24 men in 15 minutes.

Robert Harlan Horr piloted his glider to a landing in Normandy under heavy fire — he counted over 80 holes in his plane. In his pilot’s logbook, he described losing his close friend and comrade, Buck Jackson, that day.

After Jackson got hit, Horr gave him morphine and stayed by him in an open field to make him as comfortable as possible, all the while under fire from German mortars and machine guns. “Buck finally died. If I get decorated his mother is going to have that medal,” Horr wrote. “Got to move up now so that’s all for now.”

Except he was wrong: Buck, it turned out, survived. But Horr never knew it — he was killed in a glider accident back in England soon after.

More than 400,000 Americans, like Horr, were killed in the war, and wartime experiences exacted a terrible toll on many who survived.

On 28 pages of loose paper now in VHP collections, Marine Corps Pvt. Leon Jenkins chronicled the months he spent fighting on Guadalcanal and Tulagi in 1942 — events that haunted him for decades to come.

“Dawn. Everything looks so peaceful down here, but we’re sitting three miles away from hell itself,” Jenkins wrote on Aug. 8 while aboard a ship stationed just offshore.

Over the next six weeks, Jenkins found himself on the ground, in hell — day after day of air raids, snipers, assaults, shelling and hand-to-hand fighting, broken up only by rain and hunger.

On one page of his diary, Jenkins observes that he never really expected to have to kill anybody with his rifle. By the end of the next page, he’d shot and killed three Japanese soldiers, bayonetted a fourth and killed a fifth with his knife during an assault on a machine gun nest — and suffered a knife wound in the back.

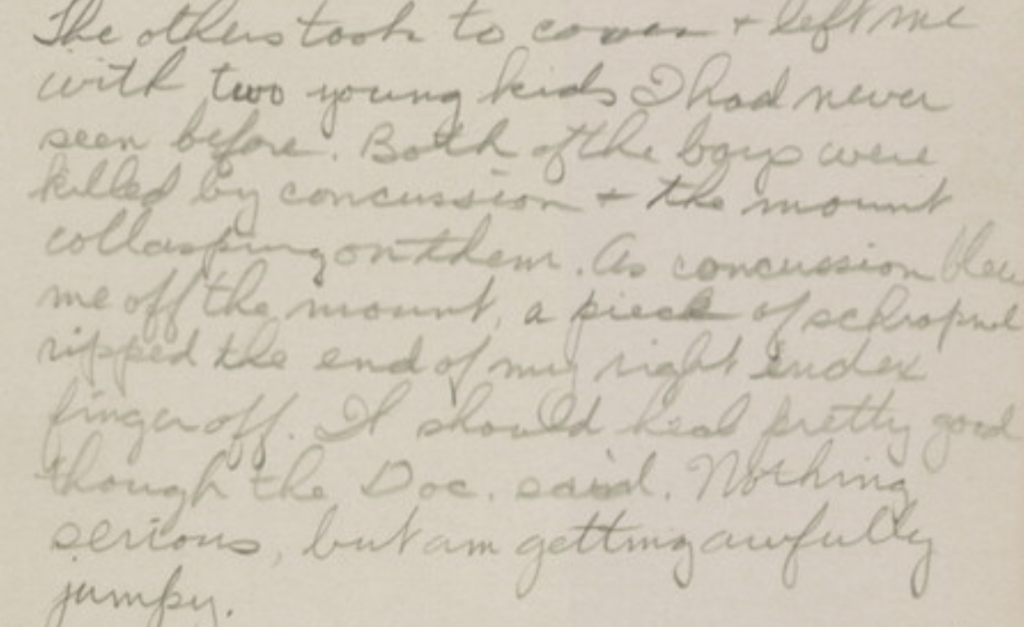

On Aug. 19, flying shrapnel cut the legs off his cot while he slept. Ten days later, a bomb concussion blew the watch off his wrist and, the next day, a piece of shrapnel sliced off the tip of his index finger and killed two comrades standing nearby.

Leon Jenkins’ diary entry detailing the death of two fellow soldiers and the loss of part of his finger. Veterans History Project.

On Sept. 2, he waited out an air raid in a small hollow, writing notes as Japanese planes approached — notes that stopped in mid-sentence when a bomb struck his position:

“I see the planes. 18 of them coming in same as yesterday. Just a little to my right. The wind’s from that way, too. This is going to be close. AA opened up + first bomb landed about 100 yds + next bomb right in line with my-”

The diary picks up two weeks later with an entry shakily scrawled from a hospital bed on an island some 600 miles away; Jenkins had a terrible headache, a worse case of nerves and no idea what had happened.

He soon was discharged, physically safe, but forever haunted. Jenkins suffered badly from post-traumatic stress disorder and struggled to make jobs and relationships work for the rest of his life.

His experiences, chronicled on humble pages that say so much, today are preserved at the Library so that future generations may better understand what Jenkins, and thousands like him, endured.

“I would go back into a burning building to save this diary. It is that important,” wrote Jenkins’ nephew, Kerry D. Ames, in donating the pages to VHP. “It speaks for one man, but it also speaks for so many men.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.